On the question of gene drives, “Africa will have the ultimate say” - but do people know they are being asked?

Published in Microbiology, Agricultural & Food Science, and Zoology & Veterinary Science

Gene drive technology offers a potent method to reduce mosquito populations in the regions most affected by vector-borne disease. A notably contentious topic; these schemes have been accompanied by public communication efforts to try and broadcast the potential benefits of the endeavour, as well as the techniques employed to mitigate the risks. A joint effort between the University of Exeter (UK), Makerere University (Uganda), and Gulu University (Uganda) has investigated the effectiveness of this ‘SciComm’ in Uganda, a nation that may host the first mass release of gene drive mosquitoes into the wild.

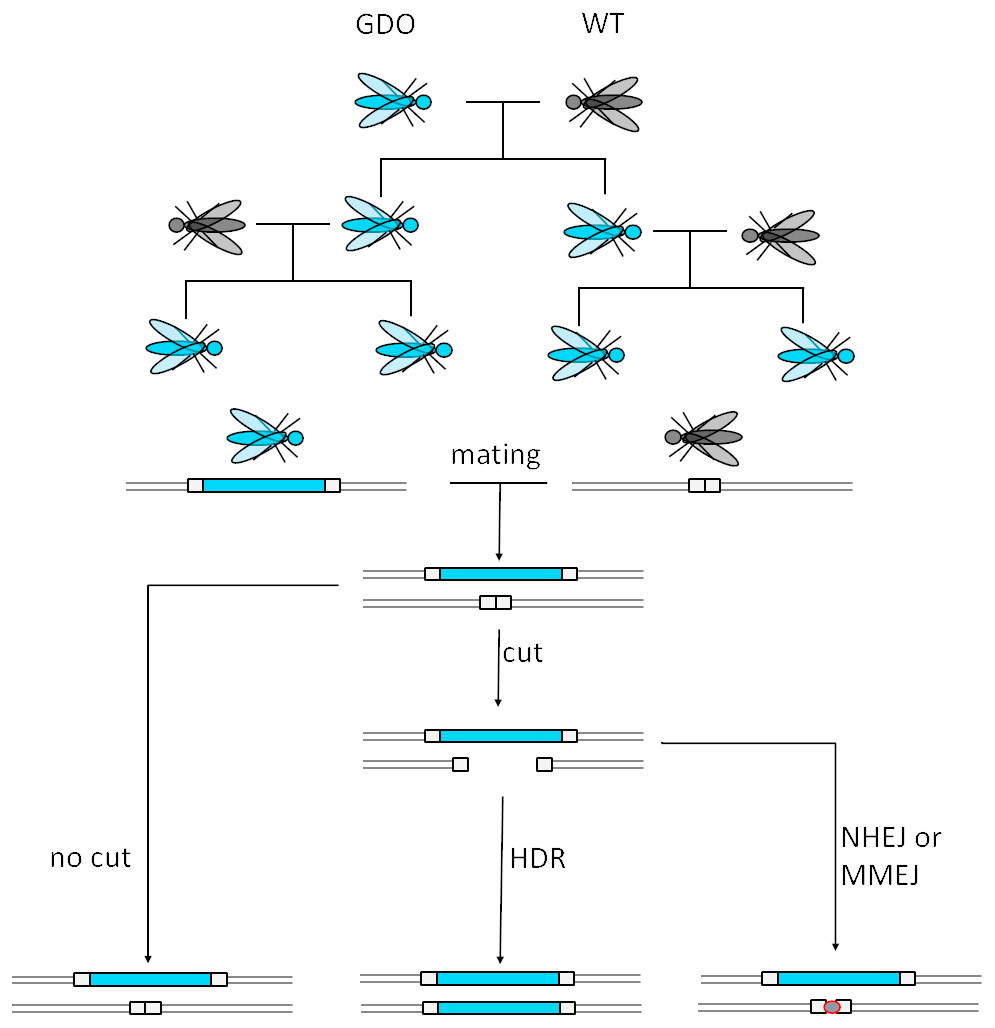

Gene drives are based on a relatively old approach to controlling the populations of unwanted creatures - adding a gene to the gene pool that inhibits the organism’s ability to grow and reproduce. The issue with releasing individuals into the wild with a deleterious gene is that natural selection has its way, and the mutation is snuffed out. The spread of the gene is further impeded by normal laws of inheritance, in which progeny obtain one allele from their mother and one from their father. A mutated parent will only ever pass down one mutated allele at most to offspring, diluting the impact of the maladaptive DNA over generations. A bad gene with no inherent mechanism of cheating the genetic system will soon be itself eradicated – but the gene drive however has no plan to play by the rules. This system partners the disadvantageous mutation with a Cas9 enzyme (of CRISPR fame) which can target the cognate allele containing the ‘normal’ gene. Hence, in biallelic offspring with one mutated and one wildtype allele, the gene drive locus digests and breaks the native allele. A homologous region of the genome is used to repair the cut caused by the Cas9; and this is the mutated allele created by scientists. Now, the progeny will have two alleles of the mutation, and so will their progeny, and so will their progeny, etc. The gene drive has implanted itself into the population.

For many readers it may already be clear how this method could generate fearful discourse. A gene that can force itself into and through a population is a frightening prospect. One immediate worry is how could it be stopped if the gene drive became something we no longer wanted? What if there are unpredicted side-effects with little recourse to correct? What if the gene drive passes between species by cross-breeding? These are sensible concerns, and a responsible communication strategy is needed to address them. Indeed, open public communication is a key part of a ‘code of conduct’ written for gene drive researchers. How scientists are mitigating the worst-case scenario outcomes, and balancing these hypothetical issues with the real and current issue of infections, is necessary for gene drives to be accepted by the people they are meant to help. One of the major players in this field is the Target Malaria consortium, encompassing both the research behind gene drives in mosquitoes, and efforts in African nations to educate about the technology, with partners including universities in Europe and Africa. Public engagement has been a core practice of the consortium, most notably so far in Burkina Faso, one of the original host nations of experimentation with the release of genetically-modified mosquitoes (not gene drives) into the wild. Although Burkinese politicians are convinced of the need for gene drives, there are many organisations that are vehemently opposed. These groups published a joint statement detailing their reticence, and claim that farmers have been protesting the governmental decision to permit the release of GMO insects. Some complaints go beyond the science itself, displaying distrust not just for the ‘colonial’ element of a technology developed in the West being tested in Africa, but also for the major funders of the research, the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation.

More recently, Uganda has been suggested by Target Malaria as the potential host for the first wild trials of actual gene drive mosquitoes. The people there suffer a major, all-year-round burden of malarial illness, so the benefits of a successful gene drive initiative could be huge. But for this to work, both practically and ethically, the local people need to be on board, and well-informed on the work being done around them. The authors of this study have hoped to ascertain what the obstacles to effective science communication, and specifically gene drive discourse, may exist in Uganda, if-and-when this nation becomes a site of actual gene drive trials.

The research begins by identifying where Ugandans tend to hear news. The media landscape of Uganda strongly skews towards the radio, although newspapers tend to be where the local stations themselves get their information form. In the absence of an archive of radio broadcasts, the newspapers offered the best chance to objectively define the penetrance of “gene drive” stories. The few articles that were found in the databases were from English-language, mostly urban focussed newspapers, and even there only a single story was written by a local journalist instead of reprinted from overseas (notably, it had a negative stance). This belied a greater issue in the Ugandan media, discussed by the authors and their interviewees; the lack of trained science journalists in the country. In contrast to the situation in, say, the UK, few media outlets have an arm of their organisation solely dedicated to scientific material, inevitably leading to a drop in both the quality and the amount of such coverage. There is some irony in the fact that newspapers in the UK, US, and Australia, dedicate much coverage to gene drives in Africa, but the African newsrooms themselves do not.

So where can people in Uganda hope to learn about gene drives, if they have even heard of it? The authors note that a crucial fallacy that many in the Global North make about nations such as Uganda is that the population has ready access to good quality information about a given topic. This requires looking past the scarcity of information in the local languages, significantly reduced internet access, and low literacy rates, of Uganda. This “information poverty” is compounded by a lack of transparency among official institutions, as well as governmental censorship. But the interviews conducted by the authors show that low understanding of gene drives is not a consequence of the lack of will. Participants were eager to know more, but struggled when confronted with where to acquire it. To academics it may seem that gene drives are discussed at length in Uganda, but these will be constrained to events held for those in academic circles, an impenetrable forum for the layperson.

When asked who would be most up for the task of communicating gene drive control of mosquitoes to the masses, the interviewees consistently returned to the same group - teachers. However, the teachers included in the researchers’ focus groups hit upon the same problem that everybody else did; that is, a lack of resources from which they can learn about the science. Even biology teachers had only a basic understanding and had tried, in vain, to access more information. When they were informed about how gene drives worked, as part of this study, the teachers displayed their knack for quickly producing engaging debate, identifying many positives and negatives of mosquito control that could be discussed. It remains the likely case that most teachers in the country are ill-equipped to meaningfully educate about gene drives.

Many participants emphasised that speaking up about gene drives does not come without a degree of personal concern. The issue is heavily politicised in Uganda (as it is in many places around the world) and to come out in support of it can be construed as being ‘in the pocket’ of the overbearing corporations pushing to exact their own ideology on their countrymen. GMOs as a whole remain a contentious issue in parliament itself, with pro-modification legislature only passing depending on the whim of whoever is in charge in Kampala. In such an environment it is not difficult to surmise why a local journalist may hesitate to publish a story on the benefits of this scheme; it is simply easier to be against it. But this is the challenge that science communication needs to rise to!

SciComm strategy has, in the long past, been bogged down by the idea that it is better that the public simply do not know, especially for controversial topics. But where scientists leave these vacuums of understanding, other actors will fill the gaps, often dubiously and sometimes maliciously. But even notwithstanding the inculcation of negative opinions of gene drives, it is antithetical to the concept of the informed consent if the Ugandans themselves are not even aware of the conversation. Work such as this should point the way towards programs to reach the greater population with informed, balanced discussions about gene drives. When people know more about why these scientists are planning to release mosquitoes by their villages and homes, then they can actually have the final say.

Cover image credit: US Department of Energy (Wikimedia).

Follow the Topic

-

BugBitten

A blog for the parasitology and vector biology community.

Please sign in or register for FREE

If you are a registered user on Research Communities by Springer Nature, please sign in

A powerful technology with life-saving potential — yet the people most affected barely know it’s coming. If informed consent is this limited, can we really say “Africa has the final say”?

Would this be approved in the Global North under the same conditions?

Hi Timothy. I really enjoyed your piece! Thank you so much! I also highlighted that research, among many others, in one of my living literature reviews on gene drive: https://monitoringgenedrives.com/community-voices-shape-the-future-of-gene-drive/release/2/

I hope that past mistakes with traditional GMOs are not repeated this time with gene drives.