The importance of island sanctuaries for bee survival

Published in Microbiology, Agricultural & Food Science, and Zoology & Veterinary Science

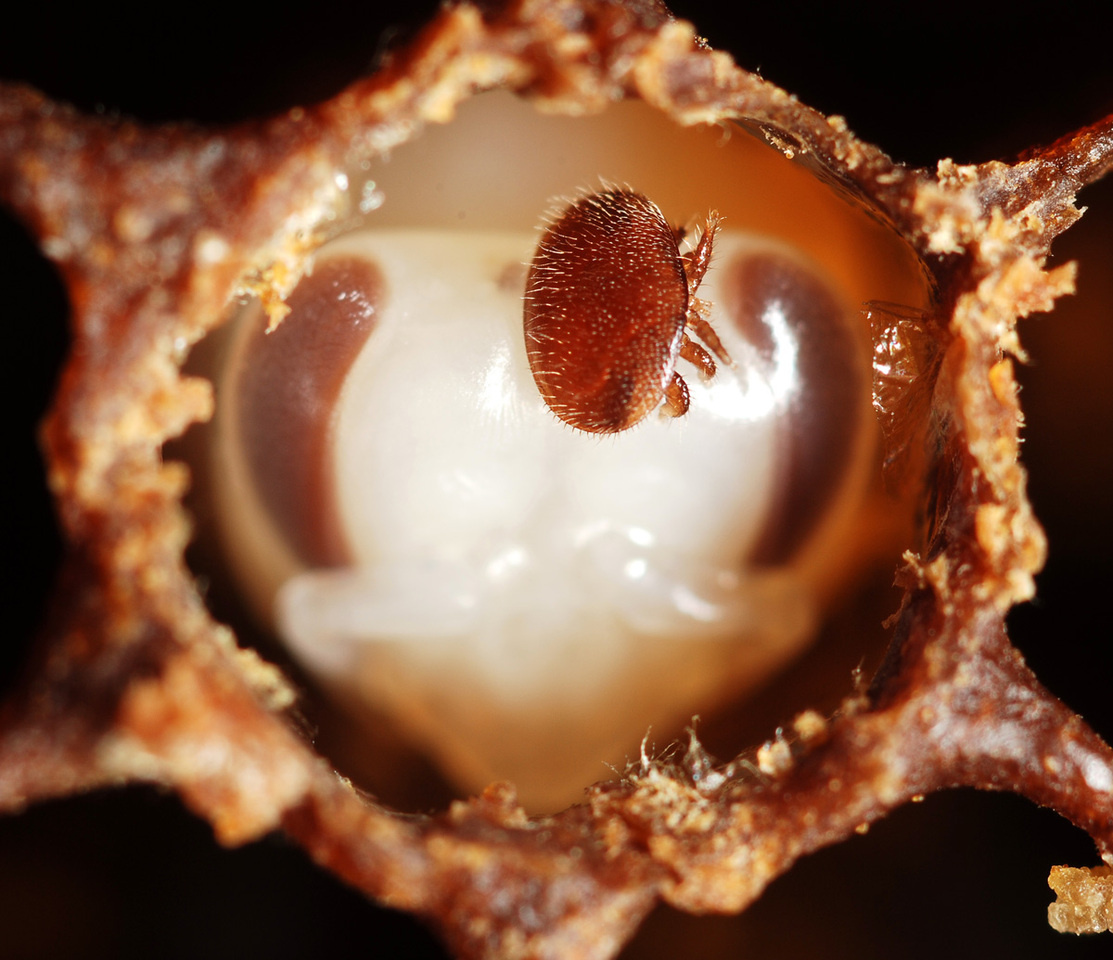

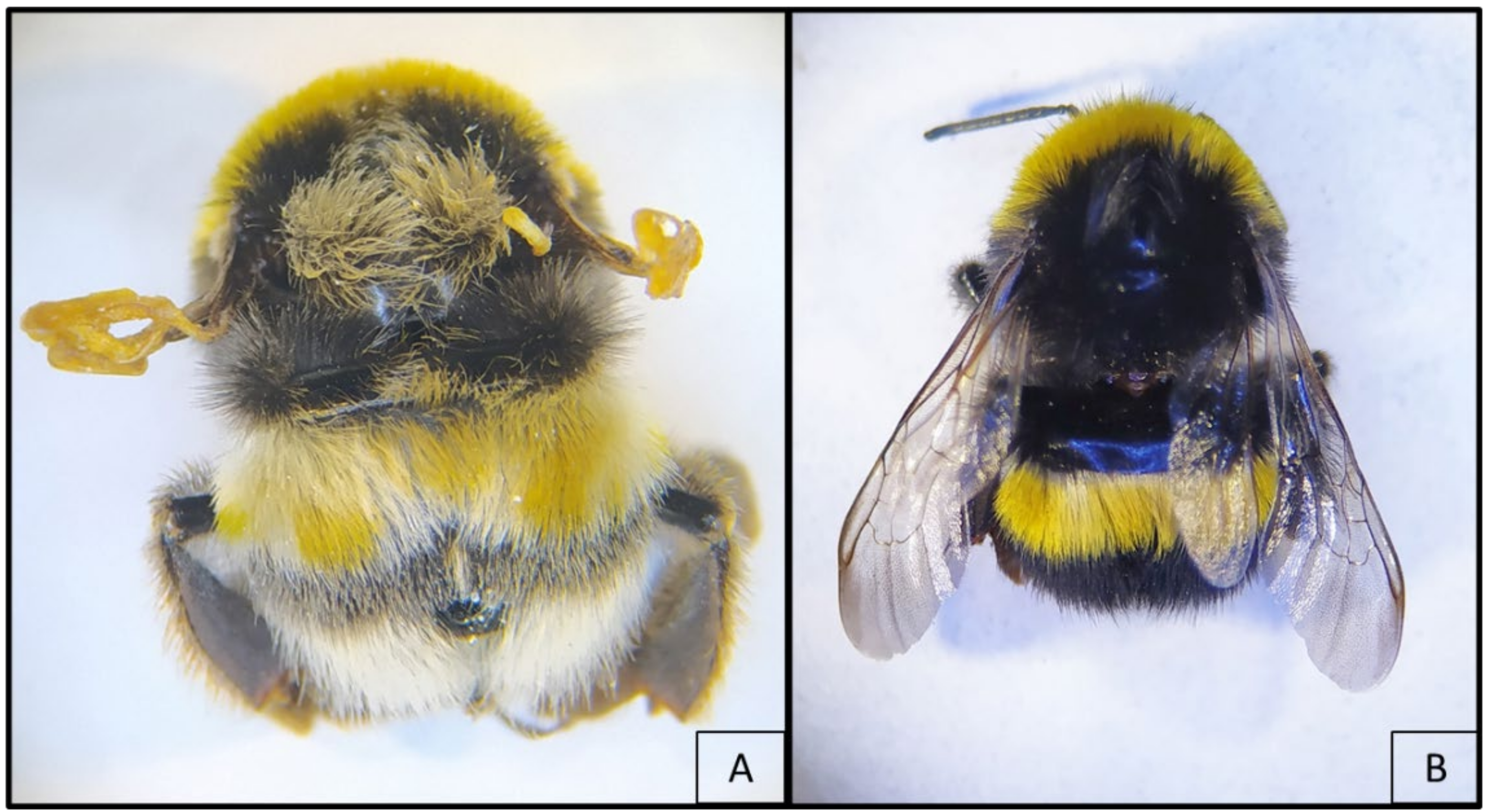

Bee populations around the world are at grave risk of viral infections. One of the most potent threats, deformed wing virus (DWV), is aided in its spread by the Varroa destructor mite vector. Although this virus originated in honeybees (Apis mellifera), the mite has helped the virus spillover into bumblebees (Bombus terrestris), leaving devastation in its wake. A recent study has investigated how being sequestered on islands, some still free of the mite, impacts the virome of these bee species, and what this tells us about the evolution of DWV, with results that may challenge our understanding of its spread.

I probably do not need to extol the virtues of bees; They make great things and pollinate many plants. They are justly appreciated by society - so long as they do not come anywhere near most of us. Like many wonderful creatures, bees are deathly threatened by disease. And like many deathly threats, this one has been potentiated to devastating effects by human influence. The Varroa vector is the direct carrier of viruses like DWV, however the transportation of honey bees for agriculture has spread this insect further than it would have by natural causes. The widespread dispersal has increased the risk of viral spillover into related species, including fellow pollinators such as bumblebees.

But the mites are not everywhere. Not quite yet. A number of islands, even those close to nations rife with Varroa mites, are still free of this bug. The bees here are not plagued by the insect. So are they both a parasite and virus-free haven? Jana Dobelmann and Lena Wilfert of the University of Ulm, Germany, set out to answer this question by sequencing the genes expressed (RNAseq) from honeybee and bumblebee specimens collected in 2015 and 2021 across a number of islands and mainland sites.

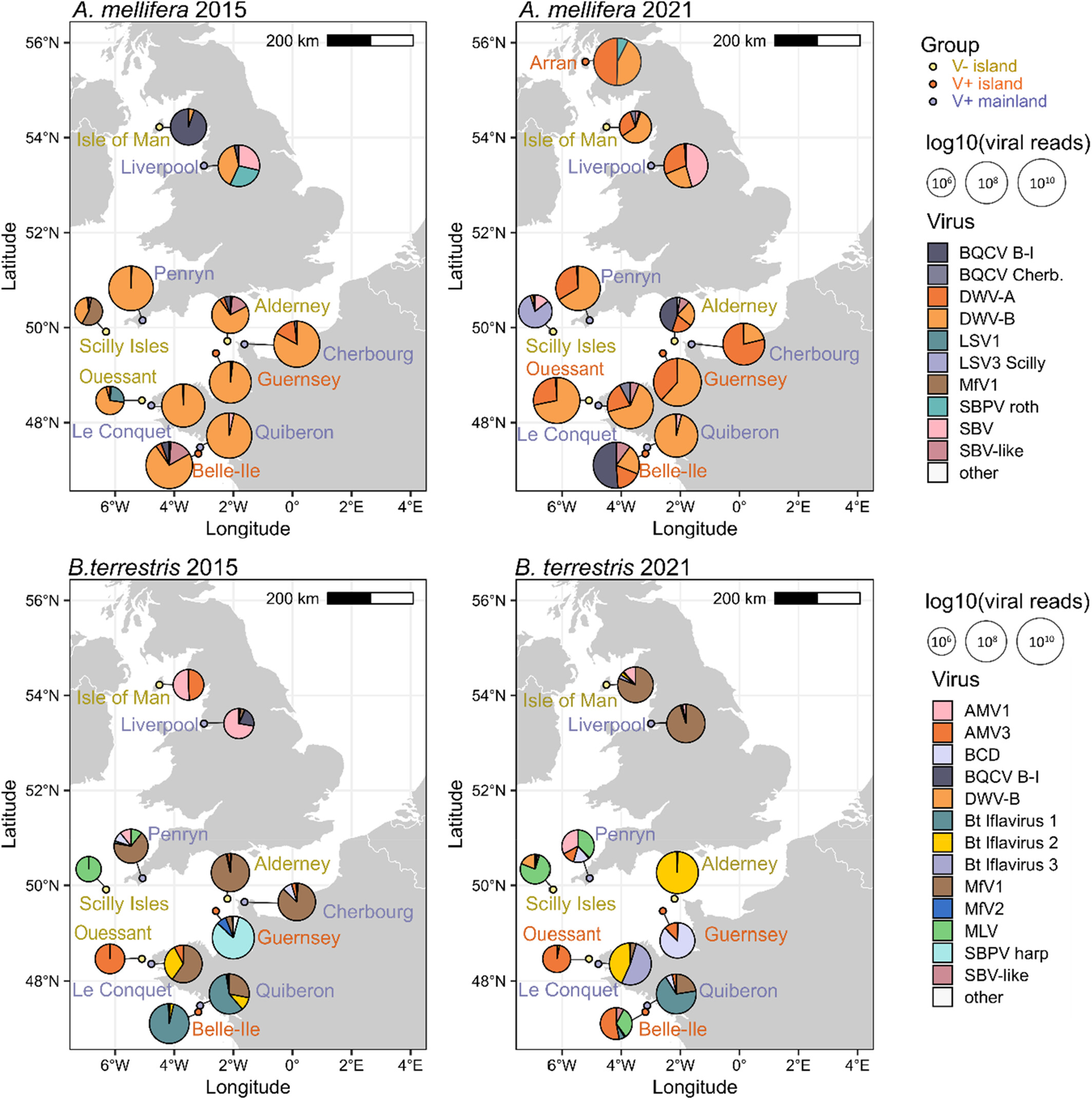

The choice of sampling site enabled intriguing comparisons to be made. All the mainland sites (across England and France) had Varroa mites present, however the islands were a mix of both mite positive and mite negative areas. The Scottish Isle of Arran and Channel Island of Guernsey were both mite positive despite their geographic isolation, whereas the Isle of Man, English Scilly Isles, and the Channel Island of Alderney were mite-free. One particularly interesting site that was included was the French island of Ouessant, which was mite negative in 2015, but the mite positive by the second visit in 2021.

Their annotation pipeline focussed on the RNA viruses - thought to be the dominant lineage of viruses that infect bees - and numerous examples were found through their sequencing of expressed RNA ‘reads’, including DWV as well as novel viral subtypes. Honeybees were profoundly more infested with virus than their bumblebee cousins, with RNA extracted from the former harbouring 13% viral reads, compared to <1% for the latter. The viral RNA among the honeybee samples was profoundly impacted by the presence of the Varroa mite, with orders of magnitude fewer reads from the mite free island samples. Indeed, comparing the species richness of viruses (the number of different viruses found in each sample) demonstrated that the mite was associated with an increased number of viruses in both bees.

When comparing the viral species found across all the samples, the clearest source of variation was the species of the host: honey bees and bumblebees had distinct viromes with little overlap. One virus that did appear in both bee species was the dreaded DWV. Among the honeybees it was dominating, although showing an expected dip in prevalence among the sequenced reads on the mite-free islands. It was substantially rarer among bumblebees, being found in only three bumblebee sites/timepoints, agreeing with previous results that the virus does not spread within Bombus populations. However, two of these DWV-positive bumblebee sites were mite-free islands. A slightly conflicting picture is beginning to emerge. Although the mite may increase DWV spread in honeybees, and general viral spread in both species, most of the few areas where bumblebees had DWV did not have the mite at all.

The picture is further complicated by huge diversity between sites and timings in the data. The RNA virome was massively variable between sampling regions, and sometimes made great changes between the years of sampling too, which is not always explained by a small number of harvested viral reads. It is not discussed in the paper whether this is indicative of sampling artefacts (like a small number of collected specimens) or whether these jumps in some areas is to be reasonably expected.

A low-dimensional representation of the different virus species abundances across sample sites and times did not appear to demonstrate any clear pattern, except for dominating variance contributed by the Scilly Isles samples. Despite this, statistical tests showed an impact of the mite on the species composition of the honeybee. In contrast, the overall viral composition of the bumblebee did not show any association with Varroa mite, and instead varied significantly by geographical region (specifically latitude) while the honey bee virome did not.

Another surprise that erupted from this data was the strain of DWV that was found among the honey bees. The DWV-A strain worldwide is being slowly dominated by a more-virulent, rival DWV-B strain. Although this transition was first suggested in 2021, the 2015 samples were already almost entirely DWV-B RNA. Instead of this being maintained, however, the reverse of what would be expected occurred in the 2021 results. The DWV-A strain made a comeback among nearly all the sites sampled, independent of region and the mite. It is suggested that these may be signs of recombinant variants between the two strains, as PCR testing of the individual bees (instead of the pooled RNAseq samples) showed >95% DWV-B co-infection where DWV-A was found.

Clearly, the Varroa mite is still a major factor impacting the health of bees, both of the honey and bumble variety. Islands free of the mite thanks to their isolation may present safe areas even when mainland insects are under attack. However, the instances of DWV among island bumblebees in this data seem to be spread independently of the bug. Furthermore, the dominant DWV-B strain may be waning on islands, perhaps because it is recombining with DWV-A to produce new hybrid strains. For the sake of our precious pollinators, we need to continue to investigate how the mite and the virus continue to impact bee populations.

Cover image credit: Pavel Klimov.

Follow the Topic

-

BugBitten

A blog for the parasitology and vector biology community.

Please sign in or register for FREE

If you are a registered user on Research Communities by Springer Nature, please sign in