Partner choice in social dilemmas can increase resource inequality

Published in Social Sciences

Cooperation is crucial for the functioning of groups and societies, allowing us to provide essential public goods like healthcare and education that enrich our collective lives. But cooperation is not always a given - from an individual perspective it is often most beneficial to free-ride and benefit from collective goods without contributing oneself. How do people solve this social dilemma between self-and collective interests?

One solution lies in partner choice: we are more likely to cooperate, instead of free-ride, when we can choose with whom we want to cooperate. That is, if one is willing to cooperate and can pick a partner that is also willing to cooperate, both individuals reduce the risk of being taken advantage of by those who want to defect. But here's the thing: we use other information to decide with whom to cooperate than purely someone’s willingness to cooperate. For instance, those who have valuable resources or productive skills might be a more popular pick for cooperation than those who lack these factors. After all, cooperating with others who have a lot, or can create a lot, might result in a larger gain for oneself. Consequently, some people are better equipped for cooperation than others, not just because they want to, but because they are!

These aspects have a profound implication for modern societies, in which inequality is on the rise. In an unequal society where people can choose their partners, those who are better off in terms of resources or productive skills might form partnerships with each other, leaving out those with fewer resources or a lower productivity. Even if those who are better off genuinely want to cooperate, they might lack the means or skills to become attractive cooperation partners. Hence, while partner choice seems like a good way to encourage cooperation in equal societies, it can inadvertently worsen resource inequality when people differ in their resources and productivity levels.

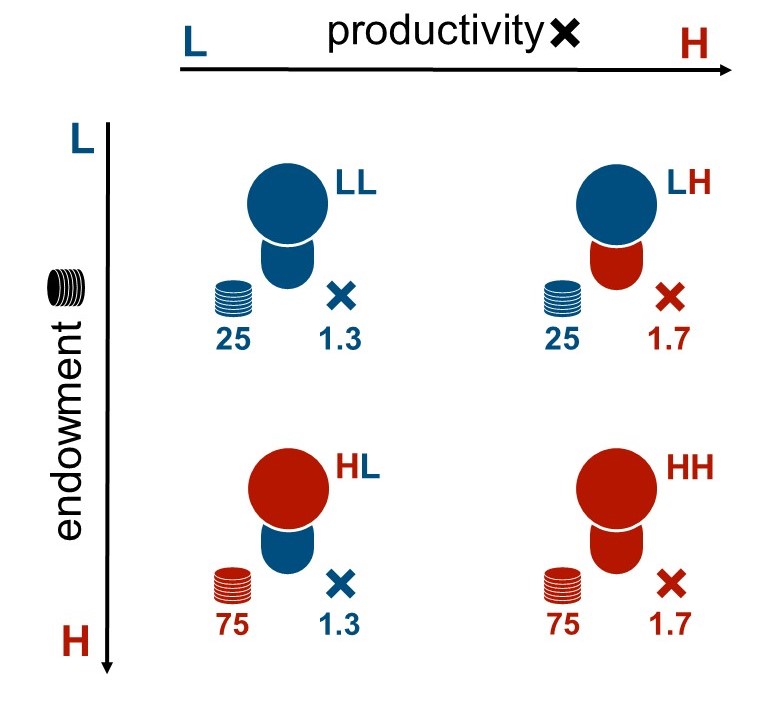

We examined this possibility in an experiment (n=336), in which individuals, within groups of eight, differed in how many resources they owned and in how ‘productive’ they were. Within each eight-person group, two participants were randomly assigned to have a high endowment and high productivity factor (HH types), two were given a high endowment and low productivity factor (HL types), two had a low endowment and high productivity factor (LH types), and two were assigned a low endowment and low productivity factor (LL types; Fig. 1). Participants engaged in a 24-round public goods game in which they interacted in pairs. Importantly, we manipulated how pairs were formed, so that in one condition, participants were randomly paired up with a partner in each round. In the other condition, participants could choose with whom they preferred to cooperate at the start of each round.

Fig. 1 Partner choice under inequality. Participants differed on two characteristics: endowment (H=75 Units, L=25 Units) and productivity (H=1.7, L=1.3), creating four different participant types: high endowment and high productivity (HH), low endowment and high productivity (LH), high endowment and low productivity (HL), and low endowment and low productivity (LL).

Segregation Through Partner Choice

In our experimentally induced ‘unequal societies’, we find that individuals, in general, prefer to be partnered with individuals who are ‘better off’ (i.e., HH types) instead of with those who are ‘worse off’ (i.e., LL types). However, in unequal societies, and also in our experiment, not all individuals can be paired with their most preferred partner. Because individuals who are ‘better off’ prefer only to interact with each other, partner choice leads to a segregation of pairs consisting of individuals assigned a high endowment and high productivity versus the rest. As a result, individuals with fewer resources and a lower productivity become forced to work together.

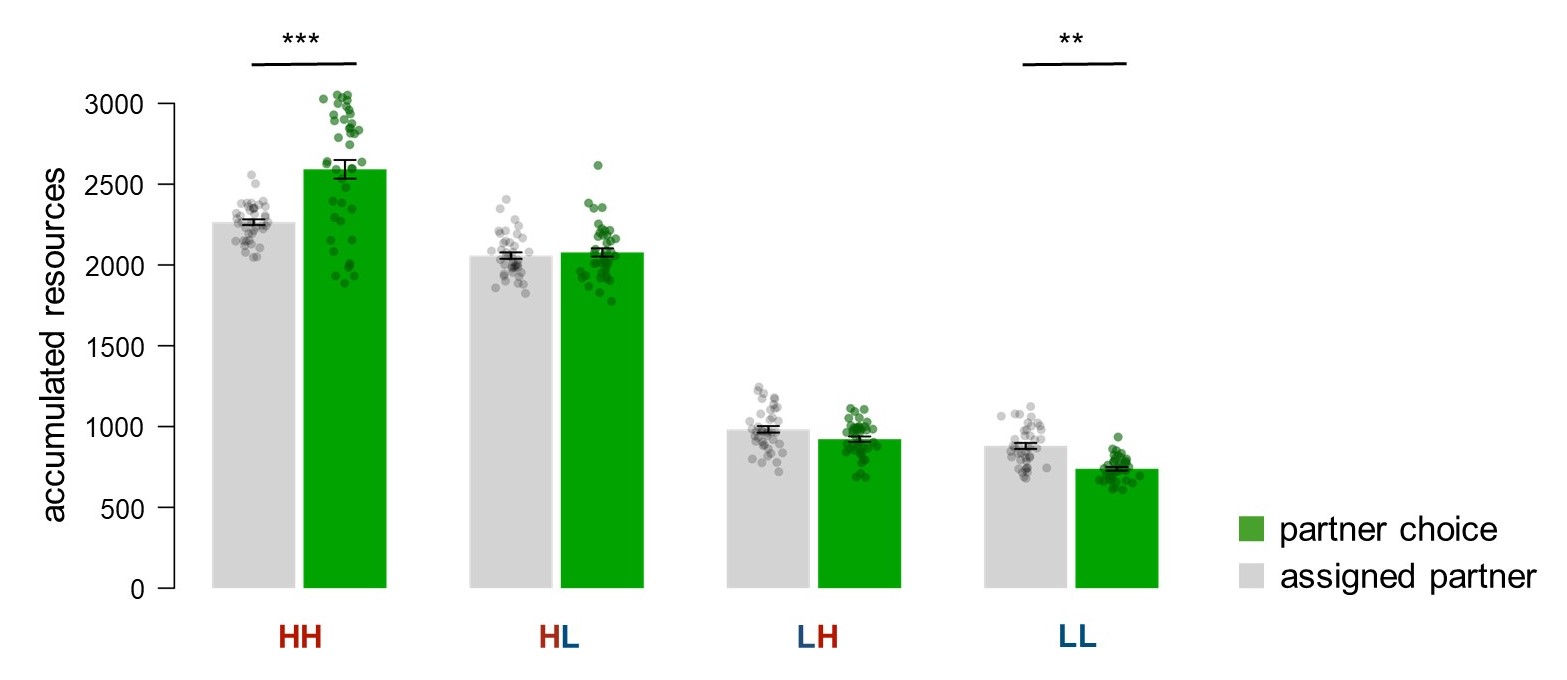

Although partner choice segregates the population, cooperation still occurs. However, the level of cooperation varies based on the partner individuals end up with. Individuals are more cooperative when paired with their most preferred (‘better off’) partner. However, if they are paired with ‘worse off’ partners, their cooperation drops. Over time, this process of partner selection and cooperation helps the ‘better off’ to accumulate even more resources, while prohibiting ‘worse off’ individuals from creating welfare (Fig. 2). This leads to a higher overall inequality, with a Gini coefficient of 0.44 under partner choice, which corresponds to countries with high economic inequality according to data from the World Bank.

Fig. 2 Partner choice can increase resource disparity. Accumulated resources per participant type (i.e., total number of units earned at the end of the experiment) in the partner choice (green bars, n=21 groups) and assigned partner condition (grey bars, n=21 groups). HH types benefit from partner choice, whereas LL types earn significantly less under partner choice compared to the assigned partner condition. Error bars indicate the standard error of the mean. ** p < .01, *** p < .001. Dots show sums per participant.

The Dark Side of Partner Choice

Whereas partner choice may enable individuals to build and maintain public goods from which everyone can benefit, we found that when individuals are unequal in terms of resources or productivity factors, partner choice can be a curse rather than cure: through partner selection, segregation endogenously emerges, and cooperation with similar others amplifies pre-existing differences between those who are ‘better off’ and those who are not.

Follow the Topic

-

Nature Communications

An open access, multidisciplinary journal dedicated to publishing high-quality research in all areas of the biological, health, physical, chemical and Earth sciences.

Related Collections

With Collections, you can get published faster and increase your visibility.

Women's Health

Publishing Model: Hybrid

Deadline: Ongoing

Advances in neurodegenerative diseases

Publishing Model: Hybrid

Deadline: Mar 24, 2026

Please sign in or register for FREE

If you are a registered user on Research Communities by Springer Nature, please sign in