Testing effect

From the cradle to the grave, testing is an integral part of everyone’s life. Children must earn their swimming diploma, students must take exams to earn credits, and professionals undergo interviews to secure jobs. Even outside formal assessments, we encounter countless everyday questions, from casual inquiries like “How was your weekend?” to factual ones like “What is the capital of Australia?” At first sight (and this is also what students typically believe), tests are just that: They query the testee’s knowledge. However, nothing could be further from the truth: Rather than a neutral tool of measurement, tests are a powerful tool for reinforcing what we already know and acquiring new information, and more so than pure study1, 2. Why is this so?

Predictive learning

Predictive learning might hold the key to answering that question. Predictive learning is a fundamental learning mechanism in both biological and computational neural networks (e.g., all AI models are run by predictive learning algorithms)3. Here, agents learn by minimizing prediction errors. For example, on a quiz night you might mistakenly predict that Sydney is the capital of Australia but then learn that the capital of Australia is actually Canberra. In this case, the high prediction error may prompt you to update your knowledge of capitals of the world. For the current story, it is important that predictions and prediction errors (arising from the mismatch between prediction and feedback) can only be generated during test, not during (passive) study. Therefore, predictive learning might drive the testing effect.

Predictive learning can account for the testing effect

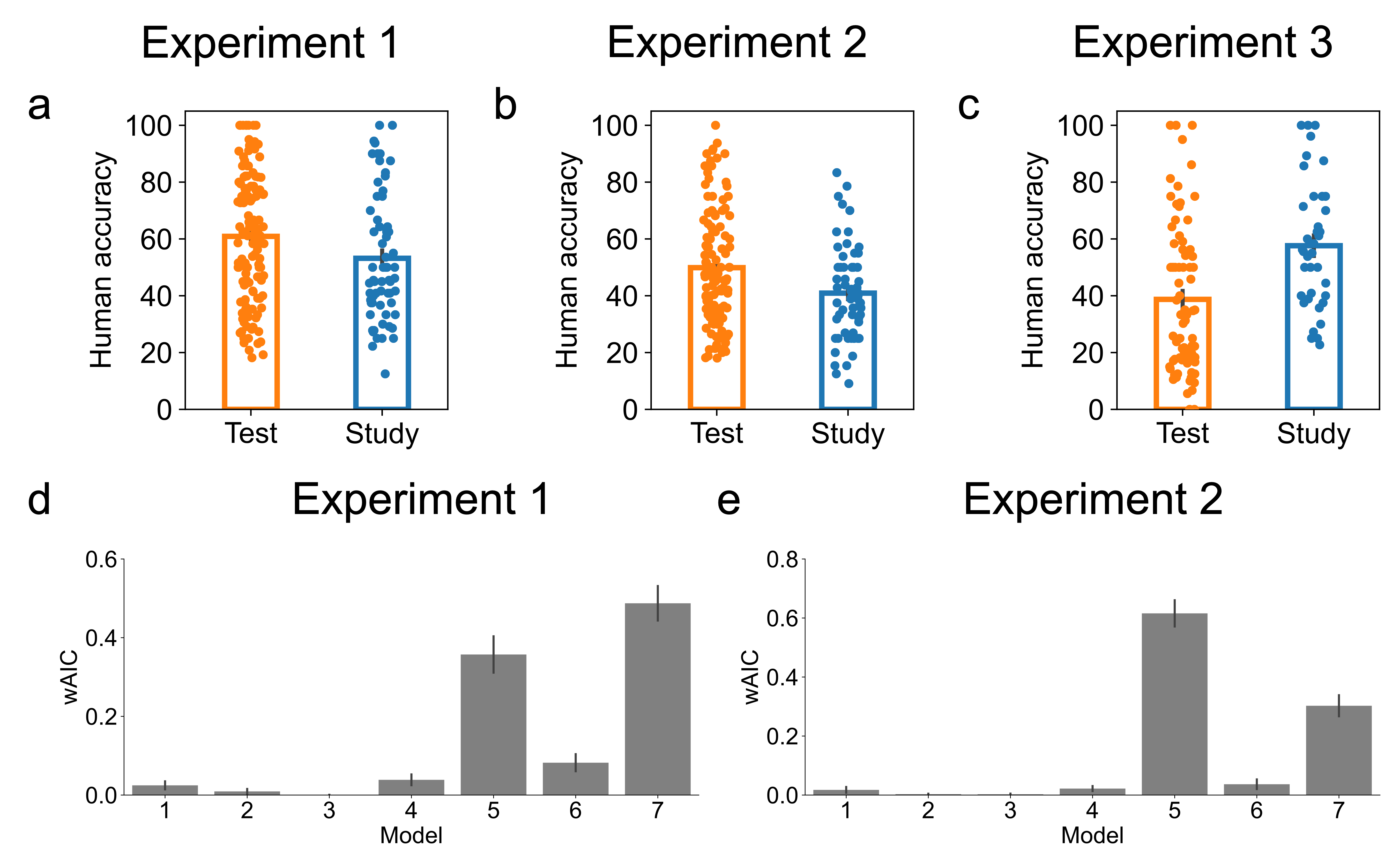

To investigate the relationship between the testing effect and predictive learning, participants in our study engaged in either testing or studying English-Swahili word pairs, followed by a recognition quiz. There was a testing effect (measured as the difference in the recognition quiz accuracy after test and study), when feedback was provided during test (Experiments 1 and 2; Figure 1a, b), but not when feedback was absent (Experiment 3; Figure 1c), emphasizing the crucial role of feedback and its associated prediction errors. Additionally, we fitted several neural network models (see the exact models in our paper), incorporating predictive learning (and/or Hebbian learning; see our paper for definition). The models were trained to perform the same task as the humans. Model comparison suggests that the model with predictive learning (Model 5) always fit the human data better than the model with Hebbian learning (Model 4; Figure 1d, e).

Figure 1 | Behavioral patterns and model comparison. a-c. The testing effect is significant when feedback is incorporated in test (Experiment 1 and 2) but is absent when feedback is absent. d-e. the model with predictive learning (Model 5) fit the human data largely better than model with Hebbian learning (Model 4). Model 7 incorporates both predictive and Hebbian learning. See the details of different models in our paper.

Summary

By integrating behavioral experiments and computational modeling, our study suggests that predictive learning serves as the cognitive basis of the testing effect. The testing effect aligns with a broader trend in cognitive and educational sciences to encourage active learning and error-driven learning4. Our predictive learning perspective explains why this matters, and we hope our paper can support this trend.

Reference

-

Karpicke JD, Roediger HL. The critical importance of retrieval for learning. Science 319, 966-968 (2008).

-

Rowland CA. The effect of testing versus restudy on retention: a meta-analytic review of the testing effect. Psychological bulletin 140, 1432 (2014).

-

Sutton R, Barto A. Reinforcement learning: an introduction. MIT (2018).

-

Metcalfe J. Learning from Errors. Annual Review of Psychology 68, 465-489 (2017).

Follow the Topic

-

Communications Psychology

An open-access journal from Nature Portfolio publishing high-quality research, reviews and commentary. The scope of the journal includes all of the psychological sciences.

Related Collections

With Collections, you can get published faster and increase your visibility.

Intensive Longitudinal Designs in Psychology

Publishing Model: Open Access

Deadline: Mar 31, 2026

Replication and generalization

Publishing Model: Open Access

Deadline: Dec 31, 2026

Please sign in or register for FREE

If you are a registered user on Research Communities by Springer Nature, please sign in