Priority populations in childhood overweight and obesity

Published in Biomedical Research, General & Internal Medicine, and Public Health

Australia is one of the most ethnically diverse countries in the world, with nearly half of all Australians born overseas or have parents who were born overseas. High rates of immigration continue to increase the cultural and linguistic diversity of Australia.

In Australia, 25% of children and adolescents are in an overweight or obese weight range. Some subgroups of the population are affected by overweight and obesity more than others – notably children from different cultural and ethnic groups; Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander; and socioeconomically disadvantaged families. These subgroups are known as “priority populations”, as they tend to have a higher prevalence of overweight or obesity in childhood.

Families from priority populations often face challenges accessing healthcare. This happens because they might not be aware of the services available, face language barriers, or encounter differences in culture. Many obesity prevention programs concentrate mainly on English speakers, potentially making inequities in childhood obesity worse for priority populations.

Identifying priority populations with excess weight in childhood

High-quality data on identifying priority populations to date has been lacking – often aggregating these groups into one category (such as those ‘overseas-born’). This is often due to a combination of factors, mainly: poor data collection on social and ethnic background; and small numbers of people from diverse backgrounds that make analysing priority populations difficult.

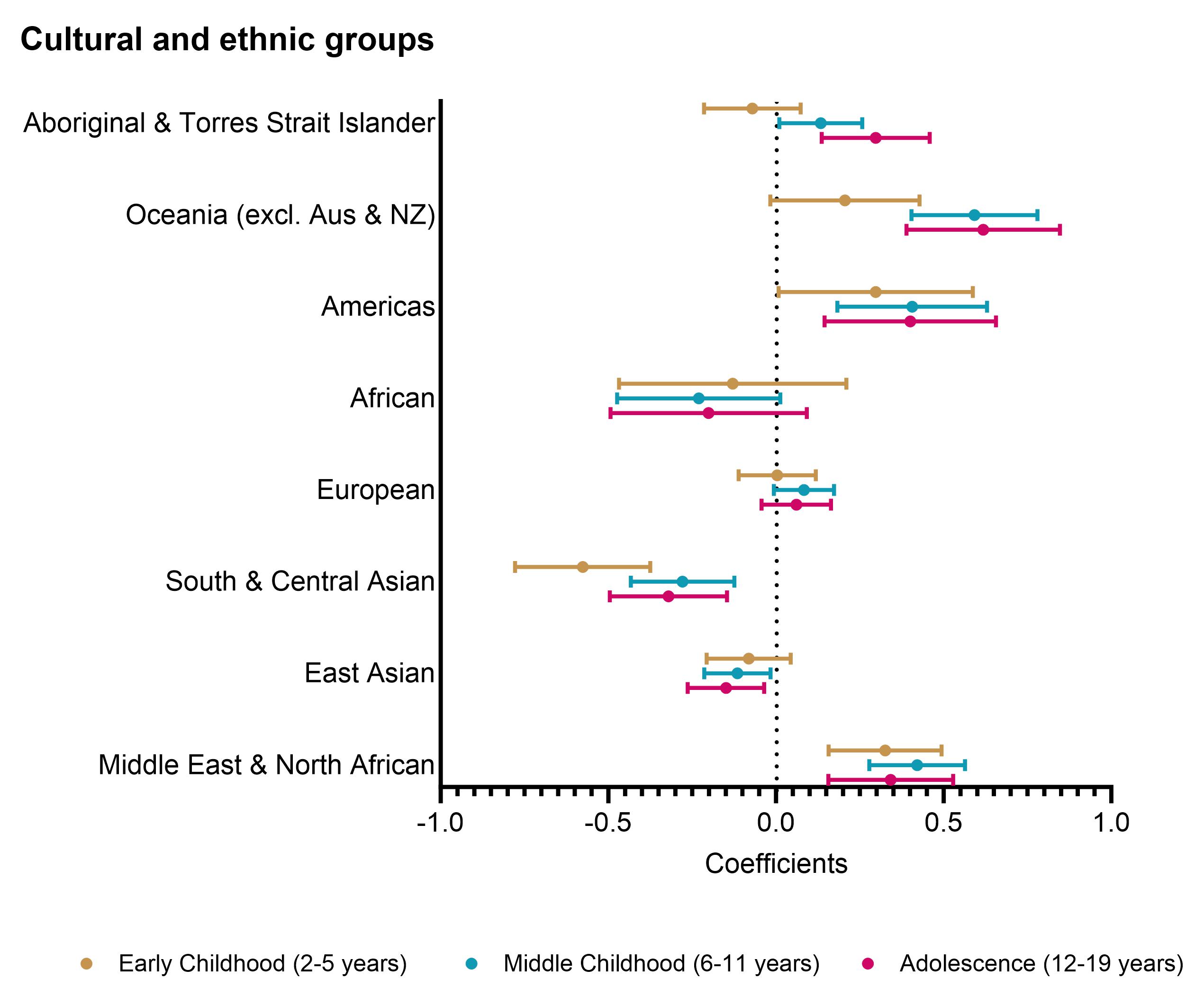

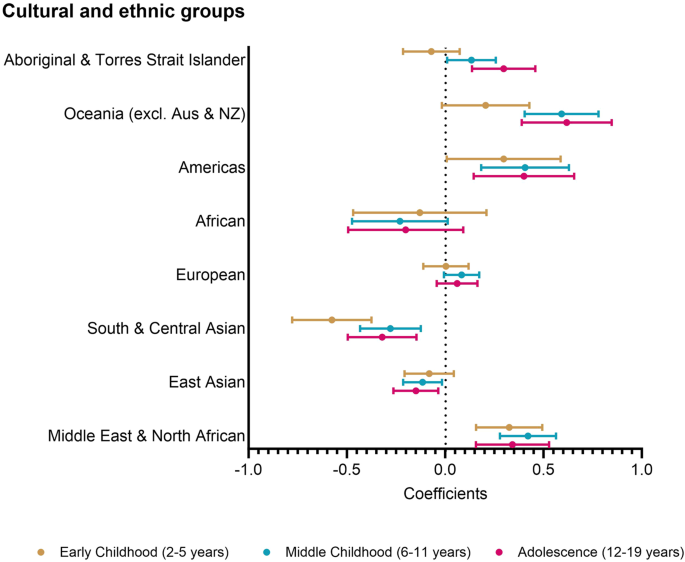

In our study, we provide insights into which priority populations are at higher risk of excess weight using the Longitudinal Study of Australian Children, which contains height, weight, ethnicity, and socioeconomic data following 10000 Australian children biennially between 2-19 years of age. We classified the children into 9 distinct cultural and ethnic groups using data collected on language spoken at home and country of birth: 1) English-speaking countries (i.e. Australia, New Zealand, UK); 2) Middle East and North Africa; 3) East and South-East Asia; 4) South and Central Asia; 5) Europe; 6) Sub-Saharan Africa; 7) Americas; 8) Oceania excluding Australia and New Zealand; and 9) Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples.

We identified whether differences in body-mass index z-score (a relative measure of body-mass index across different ages and by gender) exist between children from priority populations when compared to children from English-speaking countries. We separated our analysis into three periods of childhood development; early childhood (2-5 years); middle childhood (6-11 years); and adolescence (12-19 years).

Our findings show that across all three periods of childhood, children from the Middle East and North Africa, the Americas, and Oceania were considered “priority populations” as they had higher zBMI when compared to children from English-speaking countries. Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children had higher zBMI in middle childhood and adolescence, whereas children from European households had similar zBMI to the referent English group. Children from both Asian groups had lower zBMI.

Unhealthy weight development during childhood may be culturally patterned and distinctly different across priority populations. By splitting childhood into three periods, it showed providing healthy weight strategies for children of different ages – such as for little kids in early childhood programs, primary school kids or high schoolers may benefit different priority populations.

Further studies need to identify what are the best interventions for children from different priority populations, as what works for one group may not work for another. Currently, there is a lack of culturally tailored programs, or Aboriginal-designed and led initiatives to support healthy weight across pre-primary, primary school and adolescence. We are currently working on identifying key attributes of a healthy weight school program for Middle Eastern and North African families and developing a health economics model to identify cost-effective programs for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children.

We hope policymakers use the results of this study to take action and invest additional resources in strategies targeting priority populations to reduce disparities in overweight and obesity and improve the health of our children.

Follow the Topic

-

International Journal of Obesity

This is a multi-disciplinary forum for research describing basic, clinical and applied studies in biochemistry, physiology, genetics and nutrition, molecular, metabolic, psychological and epidemiological aspects of obesity and related disorders.

Please sign in or register for FREE

If you are a registered user on Research Communities by Springer Nature, please sign in