Prosocial Preferences can Escalate Intergroup Conflicts by Countering Selfish Motivations to Leave

Published in Behavioural Sciences & Psychology

Intergroup conflict stands out as one of humanities most pressing problems. Whether it is nations battling over territory or hunter-gatherers engaging in raids and coalitionary warfare, these conflicts are often asymmetric in structure: one group initiates an attack, and the other is forced to defend. When under attack, individuals face a critical choice: to defend their group or flee and leave their group behind. This decision carries high stakes. On the one hand, choosing to stay and fight contributes to successful defence but could result in economic losses, physical injuries, or even death. On the other hand, fleeing ensures personal safety but leaves others—potentially friends and family—to face the attackers alone.

Fight or Flight?

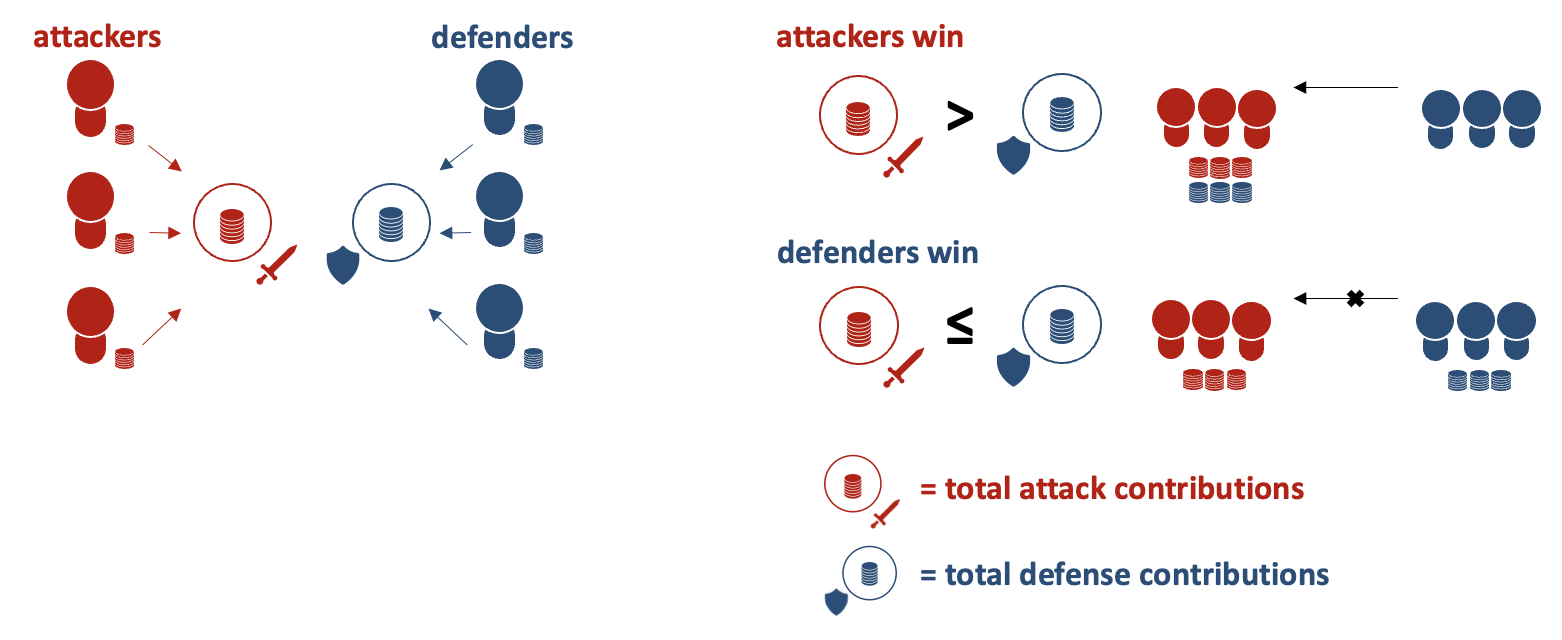

To understand when defenders fight or flee, we conducted three experiments, using a newly developed Intergroup Attacker-Defender Contest with an Exit option (IADC-E). The IADC-E divides participants into attackers and defenders (see Fig. 1 for the rules of the original attacker-defender contest). Importantly, in our IADC-E we included a so-called ‘Exit option’, meaning that defenders can choose to either stay or leave. If defenders leave, they evade the attack of the other group. If they do not leave, they decide how much of their Experimental Money Units (EMU) to contribute to conflict. This introduces a social dilemma for defenders: should they prioritise their personal safety by leaving, or should they stay and defend their group at the risk of losing everything?

Economic Costs of Leaving

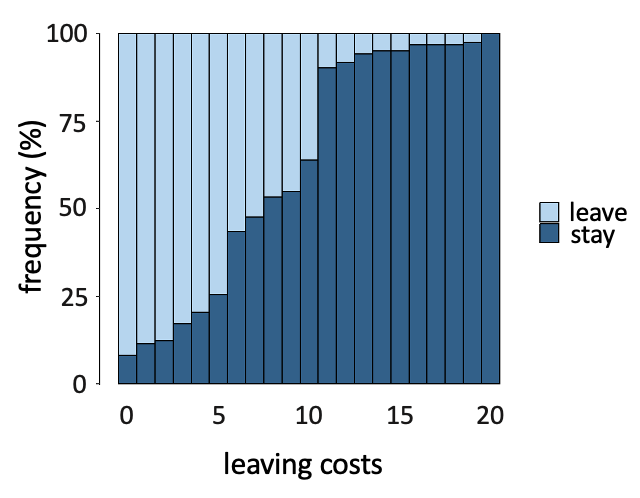

In our first study, we investigated the economic costs at which defenders choose to leave. We provided 122 participants, each acting as defenders with 20 EMUs, with options to leave at various cost levels. We found that the cost of leaving had a huge impact on whether defenders chose to stay or flee. When there was no cost to leaving, 92% of participants chose to leave the conflict. However, when leaving costed more than half of their endowment, more than 90% of participants decided to stay (Fig. 2).

Our second study involved 240 participants who, in an interactive IADC-E of 40 rounds, faced varying leaving costs: 5, 7, or 10 EMUs (out of their endowment of 20 EMUs). We found that defenders were more likely to stay i) as the cost of leaving increased, ii) if they were more risk-taking, and iii) if they defended themselves successfully on the previous round. These findings corroborate that defenders are sensitive to individual costs and benefits when deciding to leave or stay, and that they integrate past success or failure experiences in such decision-making.

Social Costs of Leaving

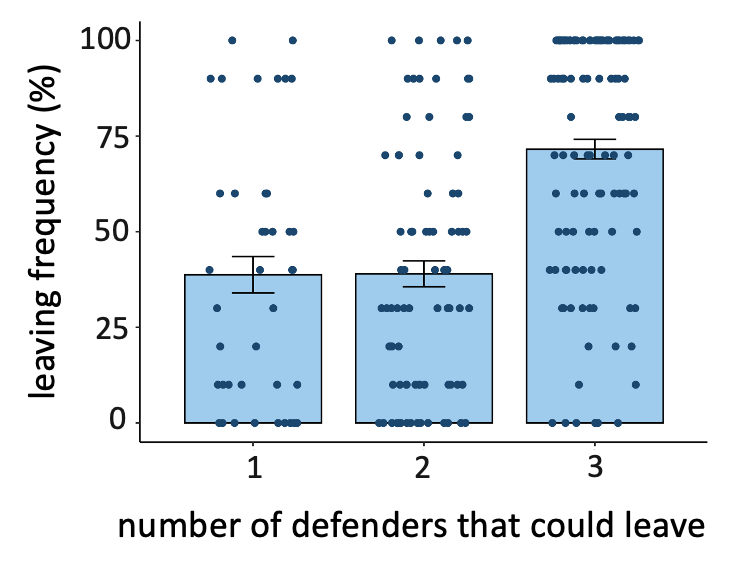

In our third study (n = 240), we shifted our focus to social costs by introducing unequal leaving opportunities. Specifically, in some blocks, only one or two defenders were able to leave for a low cost, while the rest had no choice but to stay and defend the group. Interestingly, defenders were significantly less likely to leave when other group members could not leave (Fig. 3). Staying, however, did not always mean selflessness. Some participants (36%) stayed due to strategic concerns (investing fewer EMU than the cost of leaving), attempting to benefit from the conflict contributions of those who could not leave. However, most participants (64%) stayed at a personal cost (investing equal or more EMU than the cost of leaving), thereby helping fellow group members to defend themselves.

The Paradox of Prosocial Preferences

Our experiments, besides showing how economic and social costs impact defenders’ stay-or-leave decisions, also revealed a paradox. While prosocial preferences generally encourage cooperation and collective action, they also have a ‘dark side’. Our experiments show that pro-social defenders stayed more often and contributed more to the conflict. This, in turn, led to an escalation of the conflict, with attackers increasing their contributions in response. The result? Greater economic waste and more intense fighting. Prosocial preferences, which are supposed to promote group welfare, paradoxically ended up fuelling conflict.

Follow the Topic

-

Nature Communications

An open access, multidisciplinary journal dedicated to publishing high-quality research in all areas of the biological, health, physical, chemical and Earth sciences.

Related Collections

With Collections, you can get published faster and increase your visibility.

Women's Health

Publishing Model: Hybrid

Deadline: Ongoing

Advances in neurodegenerative diseases

Publishing Model: Hybrid

Deadline: Mar 24, 2026

Please sign in or register for FREE

If you are a registered user on Research Communities by Springer Nature, please sign in