Rapid research with a pandemic bearing down: Studying the impact of mass gatherings on the course of COVID-19

Published in Social Sciences

When the COVID19 pandemic struck in January of 2020, our lab, like many other labs around the world, began to redirect resources and attention to the impending threat. We launched a study of the early spreadof the virus, an investigation of novel testing strategies in one of our field sites in rural Honduras, the development of an app (“Hunala”) for people to forecast their personal risk (which was ultimately not widely adopted – we had just a few thousands users sign up), as well as other COVID-19-related investigations.

As early as March of 2020, the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, like many other foundations, put out a call for proposals for innovative ideas that could be funded urgently and completed rapidly, and which might somehow assist the nation in addressing the threat. We pitched a series of ideas in response to this request for applications, and, on April 16, 2020, we were notified (by our program officer, Paul Tarini) that one project we pitched, “Assessing the hazard of elections during the COVID-19 pandemic to voters and to the process of voting,” was selected for a full proposal. We wrote up a full proposal, and it was funded by June of 2020. Our objective, as encouraged by the foundation, was to get results as rapidly as possible to be able to inform the elections slated for November 2020. We raced to get the data and complete the analyses for our initial results, focused just on the impact of the primary elections in early 2020, in time to release a preprint and a preliminary report showing that, in fact, it seemed that turning out to vote in the primaries did not affect the local course of the epidemic.

As we moved forward with this research, however, we decided both to greatly expand the kinds of gatherings we studied and to conduct a more comprehensive analysis that improved on existing methods. This took much longer, of course. When we began this research into the effects of political mass gatherings on the spread of COVID-19, it actually seemed logical to expect to find evidence of an increase in the spread of the virus. In fact, from early on, we were actively engaged in the effort to warn about the need for non-pharmaceutical interventions (NPIs) to postpone acceleration in the growth of infections at the outset of the pandemic, when the properties of the virus were not yet fully understood.

But, after conducting an extensive analysis of over 700 political mass gatherings across 48 states in 2020 and 2021 in the paper now published (in 2023) in Nature Human Behavior (with our coauthors Laura Forastiere and Marcus Alexander), we had to conclude that the kind of mass gatherings related to politics, which were generally impersonal and outdoors, did not seem to affect the local course of the pandemic in general (however, individual risk is another matter).

This two-year period of 2020 and 2021 featured political activity on an unprecedented scale: the Black Lives Matter protests were possibly the largest movement in US history (consisting of huge events in major American cities, up to hundreds of thousands of people, and smaller events across the country). Estimates put the cumulative number of protestors between 15-25 million people. This period also kicked off a highly fraught election season, and voter interest and participation were very high.

As we have seen over the past few years, NPIs are crucial to limit the rapid spread of the virus and to minimize the burden to the healthcare system. This is especially true early on in a pandemic, when vaccines are unavailable. We began this project amid a highly polarized debate over whether to hold large scale political gatherings. Public health officials warned that these events would endanger lives, noting their potential to become the sorts of super-spreader events that helped fuel the pandemic (for example, one wedding in Maine in August 2020 was linked to 270 cases and eight deaths, which likely altered the trajectory of the virus in the whole state). To make things worse, COVID-19 emerged during a period in which distrust in science was high—just as it became crucial to understand the impacts of an unfolding epidemic—which likely stoked conflict over the public response to COVID-19.

But the decision to impose restrictions on political events poses a dilemma for democratic societies, by forcing a tradeoff between the virtues of civic engagement and the health of the public. Furthermore, the political process relies upon an active an engaged citizenry, a process that becomes particularly important during the outbreak of an infectious illness where the public may want to hold its leaders accountable for their management of the crisis. However, political participation—involving the gathering of citizens in person to express their will—could worsen the outbreak.

This public debate began during the primary elections. In Wisconsin, Democratic lawmakers were blocked from changing the election date by Republicans. The WI Supreme Court, controlled by a conservative majority, overruled Democratic Gov. Tony Evers’ executive order to change the election date after a contentious battle. The chairman of the WI democratic party stated that the decision would “consign an unknown number of Wisconsinites to their deaths”. Poll-workers, in particular, expressed concerns about the safety of voting in WI. The election in Ohio was only cancelled after a similar controversy, where Gov. Mike DeWine ordered the polls closed.

Ultimately, over a dozen states postponed their elections, and five cancelled their in-person elections outright. Though these controversies frequently fell along partisan lines, with Republicans calling for holding elections and Democrats for postponement or cancellation, there were notable exceptions. Zeke Emanuel, a former Obama-administration health advisor argued that the risk of holding elections was low, comparable to shopping in a grocery store; and Tom Perez, the chairman of Democratic party, initially supported the decisions of governors to carry out elections and allowed elections to take place in several states. Dr. Anthony Fauci also stated that voting is likely to be safe, so long as social distancing measures are in place.

Even beyond the ballot box, the USA saw an upsurge in political activities. Donald Trump went ahead with his large political rallies, a decision that was heavily criticized by local public health officials and political commentators. The Black Lives Matter protests unfolded across the country, and occurred just as the US was in the middle of its second wave of the epidemic. Even healthcare workers became polarized: some experts worried that the BLM protests were a risk for increasing COVID-19 transmission, while over 1,000 public health workers signed a letter that minimized the health risks of participating in the protests, arguing that the political issue of racial justice outweighed any public health risks from COVID-19.

Perhaps most troublingly, however, all these debates occurred in the absence of a comprehensive analysis of the effects of political gatherings in the US. This is one of the reasons that we raced to release preliminary analyses of the early primaries so as to help inform public policy in real time.

To address this topic more definitively, however, we assembled a complete dataset of almost all political mass gatherings for the two-year period. We chose five types of political events that represented the range of prominent political activities: the US primary elections, the Georgia special election, the gubernatorial elections in New Jersey and Virginia, Donald Trump’s 2020 campaign rallies, and the 2020 BLM protests. We covered every state-wide election in which there was a significant amount of in-person voting, 100% of Trump’s rallies, and all BLM protests with a crowd of over 800 persons. Moreover, the extended time window of our study allowed us to examine the impact of events at different phases of the pandemic, with different levels of vaccination (e.g., the primaries predate vaccine rollout, and the NJ and VA gubernatorial elections were held when over 50% of the states’ populations had a complete series), and with different variants of SARS-CoV-2.

In addition to building a comprehensive dataset to test our hypothesis, we observed that many of the statistical tools used to study the impact of NPIs made assumptions that were inappropriate for analyzing the spread of a virus. As a result, we also advanced a novel methodology that was more suited to drawing inferences in this context.

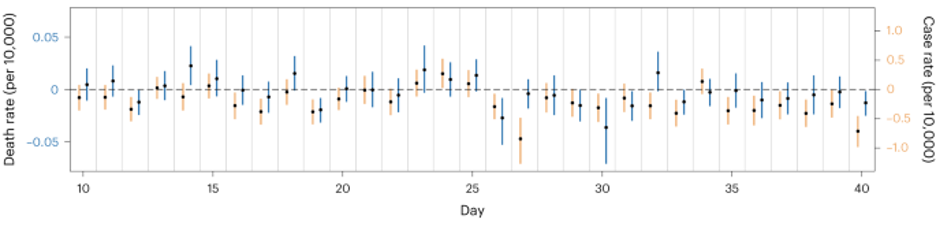

Our analysis relies on the comparison of mortality, case rates, and a measure of epidemic transmissibility (Rt) at the county level, measured each day. We compared counties that held events to, at most, the five counties that were the most similar in terms of demographics (e.g., population density), mobility patterns (e.g., the number of visits to restaurants) and epidemic characteristics leading up to the event (e.g., the cumulative death rate, the first date of a reported case).

Overall, across all political events, we found a very small decrease in the death and case rates in counties that held political events over those that did not, which were not statistically significant (e.g., Figure 1). Specifically, we found a decrease of −0.257 deaths per million persons and a decrease in cases of -20.949 cases per million persons. Additional analyses of each specific event type also yielded overall estimates that were not statistically significant, and in most cases, the changes in the wake of the events are small in magnitude.

In contrast to voting, the Trump rallies and the BLM protests were almost entirely held outdoors in the open air, though they had large crowds. Ultimately, outdoor transmission of COVID-19 proved to be rare. For example, while the Sturgis Motorcycle Rally is often cited as an example of outdoor transmission, it contained indoor events. As a result, it may be the case that political activity has a risk profile similar to shopping in a grocery store or waiting for a take-out order rather than to attending a wedding marked by sustained personal contact.

As we discuss in the paper, our results, focused on a particular class of mass gatherings, are at odds with some epidemiological studies of NPIs (which have included mass gathering bans as a possible stratagem). Yet our results are consistent with a more complex picture that is being established as researchers grapple with the set of existing conclusions. Finally, we note that the decisions individuals make and should make for themselves about whether to attend a political gathering are distinct from the overall collective impact (our study is ecological!).

Still, we consistently find no evidence for a material increase in COVID-19 mortality (or other epidemic parameters) because of mass gatherings for political expression in the USA. This lack of evidence stands in contrast to the sizeable effects estimated for some other NPIs. As a result, our study may help to underscore the importance of a policy focus on NPIs with demonstrated effects.

Follow the Topic

-

Nature Human Behaviour

Drawing from a broad spectrum of social, biological, health, and physical science disciplines, this journal publishes research of outstanding significance into any aspect of individual or collective human behaviour.

Please sign in or register for FREE

If you are a registered user on Research Communities by Springer Nature, please sign in