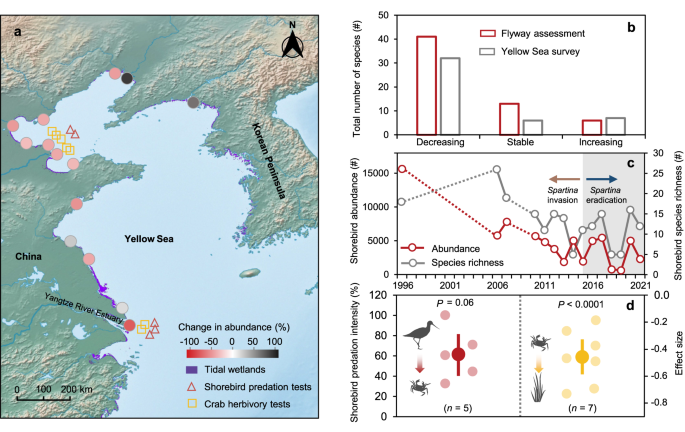

Coastal wetlands, which provide many critical ecosystem services for humanity such as shoreline protection and carbon sequestration, are increasingly degraded due to human activities and exotic species invasions. Traditional restoration methods, focusing mainly on reestablishing vegetation, often fall short in reviving these complex ecosystems. Our recent study, published in Nature Communications, unveils the utility of a new restoration approach: leveraging the ecological role of shorebirds.

In the Yellow Sea where our study was focused, invasion of the exotic smooth cordgrass Spartina alterniflora has transformed marshes formerly dominated by native plants including Scirpus mariqueter, threatening critical stopover habitat for millions of shorebirds that migrate along the East Asian-Australasian Flyway. In a coastal salt marsh in the Yangtze estuary, even though exotic cordgrass was eradicated in 2015, native vegetation has not yet recovered.

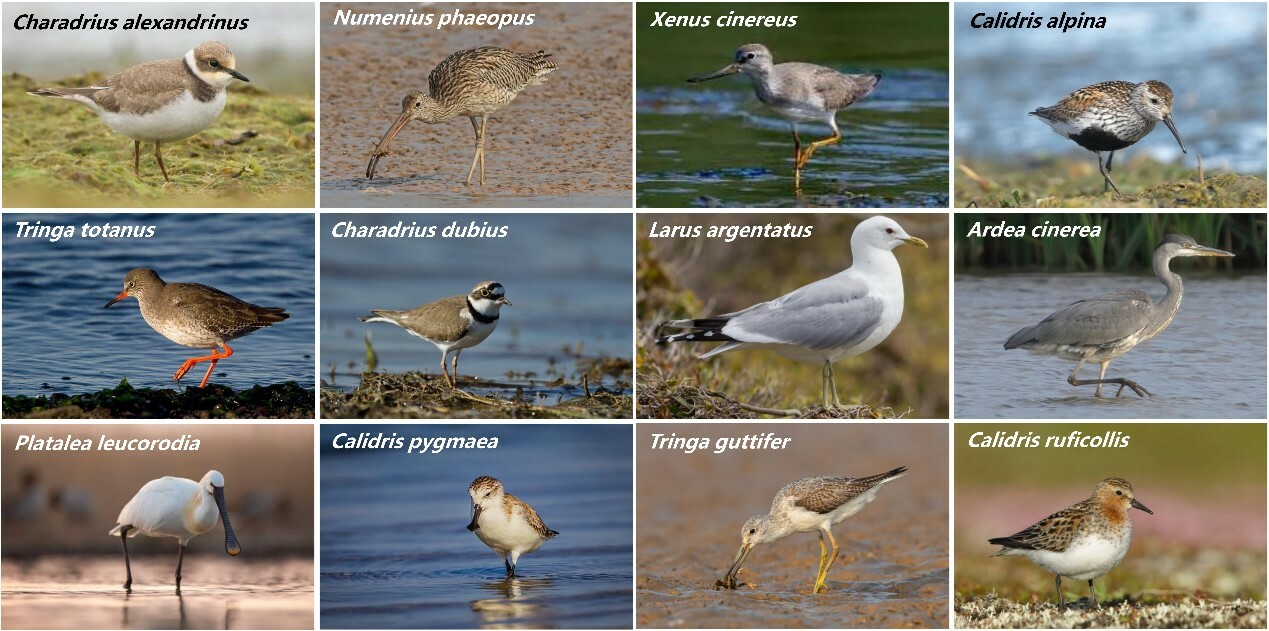

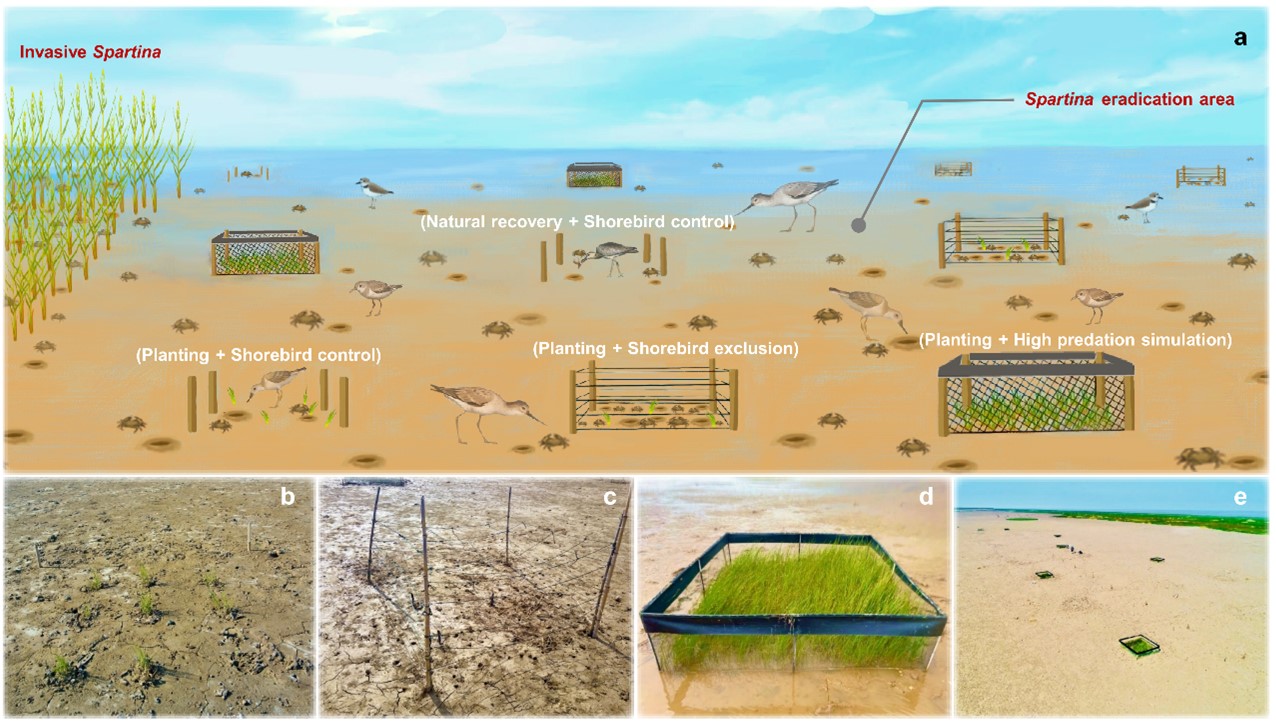

In a restoration experiment - the Coastal Wetland Trophic Restoration experiment (Fig. 1), we found that simply planting native vegetation did not lead to native vegetation recovery. Instead, we discovered that shorebirds played a pivotal role. Shorebird exclusion accelerated the loss of planted native plants, while mimicking higher levels of shorebird predation by excluding their key prey – crab grazers – allowed planted native plants to establish and recover. Thus, shorebirds, by preying on crab grazers, can initiate a trophic cascade that promotes vegetation recovery.

Fig. 1 | The Coastal Wetland Trophic Restoration experiment.

Quantifying twelve wetland functions crucial for the valued services of coastal wetlands, we further found that planting native vegetation alone did not affect any wetland functions. Shorebird exclusion significantly decreased four wetland functions including sediment accretion, sediment carbon burial, nitrogen accumulation, and soil heavy metal reduction, likely due to increased crab bioturbations. In contrast, mimicking higher levels of shorebird predation increased all of the 12 wetland functions including primary production, secondary production, wave dissipation, sediment accretion, soil respiration, nitrogen mineralization, litter decomposition, sediment carbon burial, nitrogen accumulation, and soil heavy metal reduction, except microbial production.

Interestingly, we found that shorebirds suppressed crab abundance via both consumptive effects and non-consumptive effects. Shorebirds that do not consume crabs can also affect crabs and their herbivory and bioturbation by exerting fear effects and disturbance effects.

Our findings suggest a paradigm shift in coastal wetland restoration: incorporating the ecological role of shorebirds. This could involve habitat conservation, shorebird rewilding, or simulating their consumptive or non-consumptive effects. Adopting such nature-based solutions can enhance the success of efforts to restoring these crucial ecosystems, benefiting both biodiversity and human communities. This is particularly important for achieving myriad restoration commitments in the United Nations Decade on Ecosystem Restoration.

Follow the Topic

-

Nature Communications

An open access, multidisciplinary journal dedicated to publishing high-quality research in all areas of the biological, health, physical, chemical and Earth sciences.

Related Collections

With Collections, you can get published faster and increase your visibility.

Women's Health

Publishing Model: Hybrid

Deadline: Ongoing

Advances in neurodegenerative diseases

Publishing Model: Hybrid

Deadline: Mar 24, 2026

Please sign in or register for FREE

If you are a registered user on Research Communities by Springer Nature, please sign in