Saving the insects? Nature can lend a helping hand.

Published in Ecology & Evolution

“Warm & fragrant grass, skylarks soaring in a dazzling blue sky, spring flowers dancing in the breeze… and amidst all this, me clasping a jar full of treasures: grasshoppers in all sizes, shapes and colors” – such is one of my earliest childhood memories. 1984 must have been the year, with me spending another school break at my uncle’s farm in western Flanders, Belgium. Much has changed in the mere three and a half decades that have since lapsed – not the least with the insects and surely not only in Flanders’ fields: a 2017 study showed how insect biomass in Germany’s nature reserves had declined by 75%, and a 2018 paper revealed how 98% of ground-foraging insects vanished from Puerto Rican rainforests. Our 2019 review paper in Biological Conservation detected similar perturbing trends for insect populations in many other corners of the globe. Drawing upon 73 published reports of long-term insect surveys or historical comparative studies, Francisco Sanchez-Bayo and myself recorded how -across taxa and geographies- 41% of monitored species exhibit persistent declines in their populations, insect biomass is falling with an average 2.5% annually, and every year 1% of species are added to the list of declining ones. While some taxa are critically under-studied, nearly 70-90% of e.g., dung beetles (Scarabaeoidea) and caddisflies (Trichoptera) experience rapid declines. These trends are worrying, as insects constitute vital food items for countless organisms and secure the integrity and sound functioning of the world’s ecosystems – e.g., by providing $400 billion annually worth in ‘natural biological control’.

It all started in the early 1980s with grasshoppers (or katydids, in this picture)... huge ones, with simply amazing colors!

When distilling the potential determining factors from all 73 reports, we recorded - in order of relative importance: 1) habitat loss; 2) pollution; 3) biological factors, such as pathogens and invasive species; and to a lesser degree 4) climate change. Habitat loss was noted as primary driver of insect declines in 49.7% of reports and is regularly linked to anthropogenic pressures, e.g., deforestation, canalization of surface waters, urbanization and agricultural intensification. Chemical pollution is largely ascribed to the unrelenting intensification of the world’s agricultural systems, with growing use of synthetic fertilizers and pesticides. For example, nitrogen fertilizers diminish coverage and diversity of legumes in grasslands - with negative impacts on butterfly and bumblebee pollinators. The rising use of systemic insecticides is of equal concern: these products -widely applied in a preventative fashion- are highly mobile in the water phase, are readily taken up by a (crop, non-crop) plant and mobilized to its (floral, extra-floral) nectar and pollen. As such, even while their use may be spatially restricted, their impacts can be greatly magnified and reach detritivore populations, aquatic biota or entire communities of flower visitors at non-negligible distances from the field border. Chemically-intensified agriculture not only lowers insect numbers or biodiversity, but also degrades or obliterates their myriad ecosystem functions. Yet, despite a globally-escalating use of agro-chemicals, ecologists and conservation biologists devote as little as 2% of their time, funds and energy to study (or redress) their effects on the world’s ecosystems and only pay scant attention to insects.

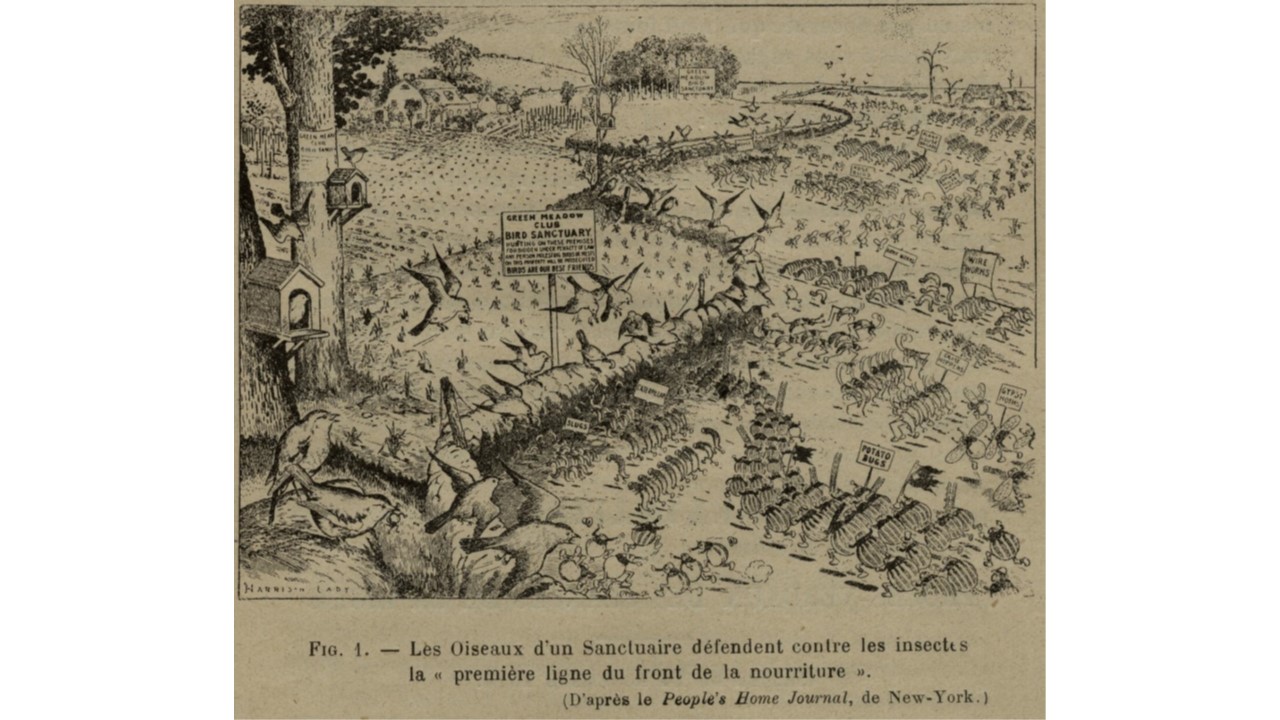

An early 1900s drawing celebrating the role of on-farm biodiversity in pest control: birds engaging in trench warfare against crop-damaging pests. Since then, the scientific discipline of economic ornithology has died a silent death & bird populations themselves are now collapsing across Europe.

To help remediate the above drivers and thereby counter-act the precipitous decline of insect populations, a critical rethinking of current agro-production schemes is mandatory. Such needs to be paralleled by drastic changes in the world’s food systems – with expanded room for diet diversification, sustainably grown fruits, nuts and vegetables and a down-scaling in the production of red meat and starchy roots such as cassava. Agricultural redesign has to happen across the world’s agro-landscapes - by weaning farmers off chemically-synthesized inputs, deliberately incorporating biodiversity and prioritizing ecologically-based, resource-conserving solutions. A uni-dimensional focus on yield-growth no longer fits the bill; the use of systems-approaches and other sustainability metrics is instead a must. Organic agriculture for example shields insect biodiversity, and consistently improves both environmental and societal outcomes; ecological intensification can transform conventional systems to equally deliver upon these twin outcomes. The establishment of wildflower strips, sowing of inter- or rotation-crops, incorporation of organic matter, maintenance of grassy margins (or flower-rich hedgerows) and 'beetle banks' to divide fields - all coupled with a drastic reduction (or all-out suspension) of synthetic pesticides - helps restore insect communities and reconstitute insect-mediated ecosystem services. Such practices have been developed and refined for cropping systems around the globe, are slowly but steadily integrated into national policies – e.g., flower strips in China’s rice production or integrated rice x duck systems, and farmers who judiciously adopt them do reap the benefits. Eventual uncertainties that might accompany such agro-ecological transition can be nipped in the bud through innovative insurance schemes and ‘mutual funds’.

In Vietnam, China and Thailand, crop diversification -through establishment of flower strips at the border of rice fields- enhances parasitoid populations, thereby reducing insecticide use by 70%, boosting grain yields and enhancing farmer incomes (Photo credit: Dieu Xuan Le, Geoff Gurr).

The establishment of buckwheat or Phacelia strips in vineyards can cut pesticide use and raise overall revenue for wine-producers (Photo: Steve Wratten)

Biological control -i.e., the conservation, active manipulation or release of pest-consuming organisms for crop protection- is a core component of those ‘ecological intensification’ measures. Beneficial insects annually deliver pest control services worth hundreds of dollars/ha in e.g., Nicaraguan cabbage, US corn or New Zealand cereals – at values that often surpass the local per-capita income. By employing biological control, pesticide-related food safety hazards can be circumvented, and ecological resilience of farming operations can be enhanced – often with unexpected, positive spillover benefits for the global economy or biodiversity conservation. Yet, many farmers remain totally unaware about those ‘hidden’ allies that operate in the undergrowth and in today’s internet era, their online visibility is even further declining. Though certain countries -e.g., France, Germany or the UK- and the International Organisation for Biological Control IOBC make efforts to raise the public profile of biological control as desirable alternative to pesticide-based measures, much more is needed to raise awareness and to shape associated decision-making in developing countries and emerging economies in the Global South. Well-designed communication campaigns, applied (field-level) research, facilitated multi-stakeholder innovation and supportive policies can all ensure that ecologically-centered practices continue to encounter fertile ground across the globe.

John Holland (Game and Wildlife Conservation Trust) trains British farmers on how to identify good bugs & assess their on-farm population levels. A truly eye-opening experience for many of today's farmers! (Photo credit: John Holland)

China and Vietnam are leading the pack when it comes to regenerative farming and non-chemical pest control. Here, at parallel hands-on training events in Hanoi and Beijing in 2017, Jonathan Lundgren (Ecdysis Foundation, USA) teaches local students and junior faculty about ways to enhance beneficial insects in farmland.

The era of ‘chemical farming’ is coming to a close: what started in the 1950s as a sensible way to clean out stocks of WWII combat chemicals has to make way for an agro-ecological transition. Here, the prime beneficiaries will not only be our minute invertebrate allies - but human society at large. By joining the agro-ecology research ranks, we scientists ensure that tomorrow’s youngsters can still admire -wide-eyed & with a sense of wonder- a jar filled with insect treasures.

Please sign in or register for FREE

If you are a registered user on Research Communities by Springer Nature, please sign in