On-farm biological control helps spare land & shields biodiversity

Published in Ecology & Evolution

Across the globe, insect numbers are declining - and, with them, vital ecosystem services are being undermined. One of those is the natural regulation of crop pests, weeds and pathogens; a service termed ‘biological control’ and conservatively valued at $4.5-17 billion annually for US agriculture alone. Biological control – including the use of judiciously-selected non-native species to control invasive pests – has a long and rich history; characterized by hundreds of success stories and a few ill-fated failures. The latter often linger longer in people’s minds and tend to eclipse the good work that has been done by dedicated and responsible scientists over the course of >100 years. However, the misguided 1930s release of Cane toads into Australia or the introduction of thistle-feeding weevils in North America lay far behind us & scientists have drawn important lessons from them: biological control now presents a safe and effective tool to permanently resolve invasive species problems.

Invasive species are inherently tied to global trade. Globally, our reliance on internationally-sourced commodities continues to increase exponentially: Brazilian soybean is fed to Flemish hogs, Florida orange juice is poured on China’s breakfast tables, and Cambodian tapioca starch makes its way into French cosmetics. This expanding international commodity trade facilitates the global proliferation and spread of invasive species, and augments their associated human, financial and in turn environmental costs. One trade-facilitated pest invader, the cassava mealybug Phenacoccus manihoti (Hemiptera: Pseudococcidae), made its accidental arrival in Southeast Asia in 2008, inflicting 18% yield losses and driving up cassava (starch) prices in Thailand and across the globe. To help meet worldwide demand for cassava-derived commodities and to sustain Thailand’s burgeoning starch sector, cassava cropping area in neighboring countries expanded with >300,000 ha by 2011. Crop area growth was paralleled by surging rates of deforestation (as tracked using Terra-i satellite-based monitoring), with substantial forest loss in cassava crop expansion areas in both Vietnam and Cambodia.

During 2014-15, trained surveillance teams screened >500 cassava fields across the Greater Mekong sub-region, recording mealybug infestation pressure and establishment rates of Anagyrus lopezi; here a field is visited in northwestern Thailand. Photo credit: Phanuwat Moonjuntha (Thailand Department of Agriculture).

Mealybugs cause distinctive stunting and deformation of cassava growing tips, leading to so-called ‘bunchy tops’. Mealybug outbreaks in 2008-2009 triggered price surges of cassava products, prompting a rapid progression of the agricultural frontier & accompanying deforestation. Photo credit: Phanuwat Moonjuntha (Thailand Department of Agriculture).

Following large-scale releases of a host-specific parasitoid, Anagyrus lopezi (Hymenoptera: Encyrtidae) from mid-2010 onward, P. manihoti outbreaks were suppressed, crop yields recovered and the pace of cassava area growth (and associated deforestation) slowed. This millimeter-long wasp was originally discovered in 1981 in Paraguay (South America) by entomologists of the Consultative Group of Agricultural Research (CGIAR) and CABI, and resolved invasive mealybug problems throughout Africa’s cassava belt – thereby averting widespread famine and allegedly saving the lives of 20 million people. Dr. Hans Herren - the Swiss scientist who spearheaded the biological control program at the time - received the 1995 World Food Price for this majestic undertaking. Not only did the Africa-wide biological control campaign generate some of the highest all-time impacts of the entire CGIAR group, it was also embraced as a cost-effective pro-poor technology and continues to generate benefits that far surpass US $120 billion.

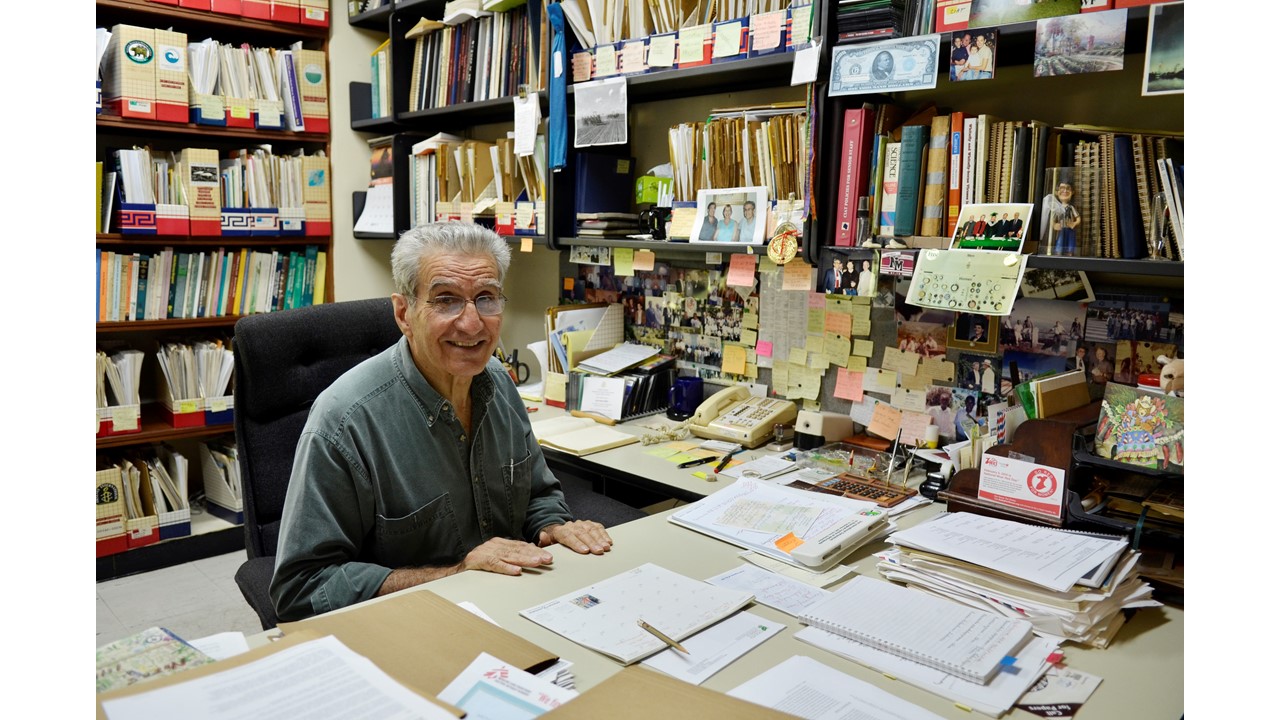

The late Anthony Bellotti - one of the entomologists who initially discovered the parasitoid Anagyrus lopezi in 1981, in remote areas of Paraguay (South America). Since its discovery ~40 years ago, this minute wasp has saved nearly 20 million African lives, generated billions of dollars of benefits and resolved invasive pest problems across two continents... without any negative ecological side-effects.

Different species of exotic mealybugs are found on this cassava stem in eastern Thailand. Photo credit: Phanuwat Moonjuntha (Thailand Department of Agriculture).

In 2009, this same parasitoid was sourced from Benin (West Africa), in an effort orchestrated by the Thai Royal Government, the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO), and CGIAR centers. Through a UN-IFAD program, I myself was out-posted in Vietnam in 2013 and teamed up with collaborators across Southeast Asia to document the multi-faceted benefits of this unique biological control endeavor.

Our study published this week in Communications Biology shows how biological control slowed the progression of the agricultural frontier and helped avert habitat loss. We document how inter-country commodity trade expands the environmental impacts of invasive species, but also how scientifically-guided biological control stabilizes crop yields and farm profits, restores balance in invaded ecosystems and safeguards tropical biodiversity - at a macro-scale. By concurrently illuminating the harmful and beneficial impacts of P. manihoti and A. lopezi respectively to e.g., conservation biologists and ecosystem modelers, we hope to enlist them in a concerted search for 'win-win' solutions that balance pest management, profitable farming and biodiversity conservation. This compelling case accentuates why insect biological control should be valued instead of being avoided; the mealybug invasion legacy (i.e., swathes of logged forests and chemically-intensified monocultures) now provides the best light to consciously prioritize agro-ecological solutions for the intensification and ‘modernization’ of (tropical) agriculture.

In Indonesia, the mealybug continues to spread eastward into areas where cassava is an important food staple. Here, teams in Lampung are gearing up to track its spread into Sumatra.

When developing our manuscript, it came to mind how insect science -or entomology- is routinely disregarded or even belittled, and how basic biodiversity research is all too often neglected. It isn't that uncommon for biological control professionals to receive messages that "in modern-day science, there is no room for those who study bugs hiding under a rock". Also, in certain highly-regarded international research bodies, weathered field entomologists and taxonomists are steadily making way for armchair geneticists and computational biologists - possibly leading to a grave disconnect from the intricate ‘real world’ ecological processes that occur within farmland ecosystems. Instead, with vanishing insect populations across the globe, more ‘boots on the ground’ are needed to characterize, understand and effectively manipulate those kinds of interactions. Micro-hymenopterans such as Anagyrus lopezi constitute nature’s best bet for (invasive) pest management, and urgently wait to be studied… before they are gone. Once they are no longer, chemical insecticide sprays might indeed be the only option left.

Follow the Topic

-

Communications Biology

An open access journal from Nature Portfolio publishing high-quality research, reviews and commentary in all areas of the biological sciences, representing significant advances and bringing new biological insight to a specialized area of research.

Related Collections

With Collections, you can get published faster and increase your visibility.

Forces in Cell Biology

Publishing Model: Open Access

Deadline: Apr 30, 2026

Signalling Pathways of Innate Immunity

Publishing Model: Hybrid

Deadline: May 31, 2026

Please sign in or register for FREE

If you are a registered user on Research Communities by Springer Nature, please sign in

Congratulations on the paper. Very nice combination of field survey, economic analysis and satellite remote sensing interpretation to generate new insights on the impacts of the cassava mealy bug and its natural enemy. I especially like the photograph of Tony Bellotti in the blog post above. The remarkable thing about all that mealy bug research is how it continues to pay off into the future. Tony would be very happy to know about all these new insights. He loved translating science into agricultural research for development.