Second Only to the Sea: Early Horticulture on Mabuyag, Torres Strait Islands

Published in Ecology & Evolution

Aboriginal and Torres Strait customs teach us to pay respect to the Goemulgal, of Mabuyag Island, the ancestral and contemporary custodians of the archaeological site, Wagadagam Village, and the material and results acquired from this research. Due to their support and only from their permission, field work and subsequent archaeobotanical research at Wagadagam was permitted.

The site is Wagadagam, an ancestral village of the Goegmulgal people and centre of the Koey Awgadhaw Khazi moiety (the crocodile). Wagadagam is located on the northwest coast of Mabuyag Island abutting Dhadhakul valley. The site contains a complex of rectangular stone cairns, linear and curvilinear stone arrangements, and abandoned garden terracing. Excavation of one abandoned terrace revealed a deep history of local environmental management beginning c. 2145-1930 cal BP and intensive forms of cultivation at 1376-1293 cal BP.

Overlooking a recently burnt Wagadagam village site. The locals were kind enough to burn the area prior to archaeological survey, making our job much easier. Photo: Duncan Wright.

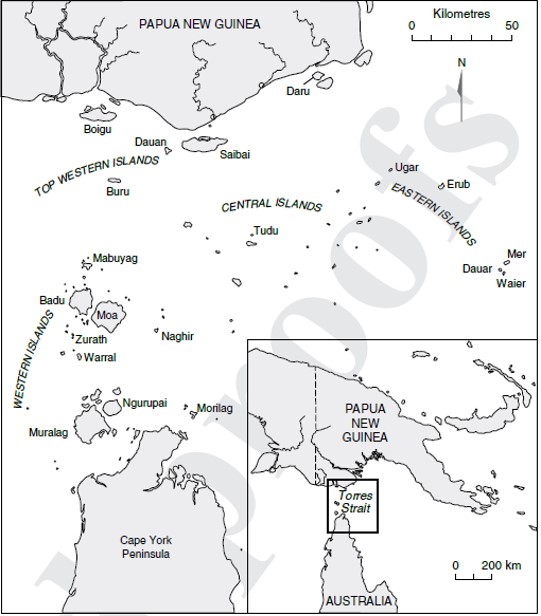

Zeneadth Kes, otherwise known as the Torres Strait Islands, is a semiautonomous region of some 274 islands between the tip of Cape York, Queensland, and the southern coastline of Papua New Guinea. Torres Strait Islanders are seafaring peoples that engaged in the largest maritime economy in Australia. The maritime network consists of entangled yet autonomous islands and mainland communities that engaged in trade, exchange, marriage and warfare. This involved the multilateral movement of various cultural paraphernalia, including ceremony, in north to south and east to west directions across the Strait. Despite this, the region has been variably described as a boundary, bridge, barrier and cultural filter separating Australian “hunter-gatherers” and New Guinea “cultivators”.

The records of the first Europeans to sail through the shallow strait and the ensuing work of academics like David Harris have shown that horticulture was variably practised, with some communities involved in minor cultivation and others with what could be called intensive dry- and wet-land systems. This begs the question, a crucial one concerning Torres Strait prehistory, at what point did cultivation become important and why was it only variably practised?

It is this less celebrated and under researched, yet important element of Torres Strait culture, that prompted this study undertaken by co-author Robert Williams as a master’s project at the Australian National University, Canberra. Training in microbotanical methods was commenced under guidance of co-author Dr Alison Crowther, at the University of Queensland. Borrowing methods from palaeobotany, we processed bulk sediments excavated from one of Wagadagam’s abandoned terraces, and the samples microscopically scanned for starch and phytolith microfossils, and an ancillary count of microcharcoal.

This multiproxy microsfossil analysis had two primary objectives. The first, qualitative in nature, compared the morphology of archaeological starches and phytoliths with those from our reference archives. This approach has been successfully used to identify diagnostic starch granules and phytoliths from archaeological contexts that match with those produced in common cultivars. It has also shown the dispersal or transplantation of domesticates beyond their native range, providing a useful proxy for studying the spread of agriculture. The second objective was the quantitative comparison of grasses versus shrub and arboreal phytolith classes. Phytolith studies have a long-standing place in environmental sciences. Generally, they provide proxies for climate change, vegetation reconstruction, environmental disturbances, tracking plant domestication and several residue applications. The idea is a straightforward one, diachronic increases or decreases in vegetation classes (e.g. grasses), articulated vertically from the top to the bottom of the archaeological sequence, are indicative of environmental and vegetation changes brought about by things like climate change and/or human activities, such as increased clearance prior to cultivation.

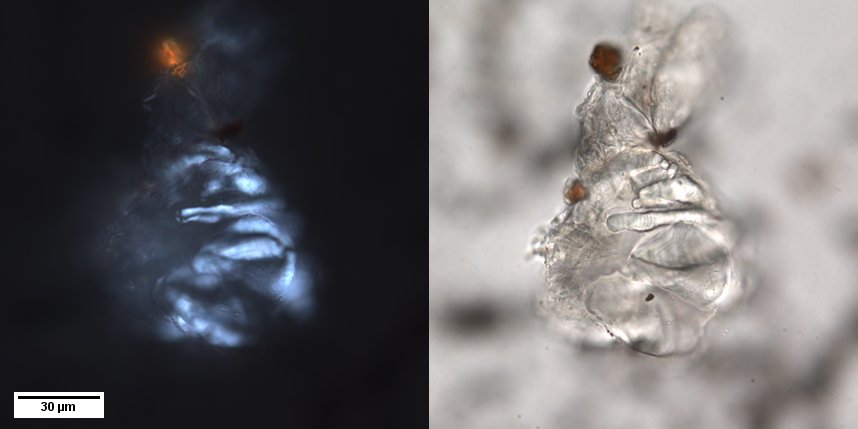

The manual scan of microscopic slides is a labour-intensive process. I counted over 5000 phytolith microfossils and studied hundreds of starch grains isolated from the archaeological/excavated soil. This probably worked out to one hundred or more hours on the microscope. Nevertheless, I identified morphologically distinctive banana (Musa spp.) fruit starch that clustered in soils accumulated at the base of the garden terrace. A multitude of silica bodies were isolated from the Wagadagam sediments, which included typical troughed bodies and tabular or irregular papillate bases diagnostic of banana leaves. Finally, phytolith evidence revealed a shift in vegetation classes from arboreal to grasses beginning near the base of the wall. Taken together, these lines of evidence provide robust evidence for increased landscape clearance, greater investment in horticulture and demonstrates that banana was grown at the site over a millennia ago. The results add a key piece to the puzzle that is the prehistoric spread of horticulture and banana in the Pacific region.

For the moment, observing that more research is necessary, the Strait appears to have acted as barrier preventing the dispersal of Indo-Pacific cultivars into Cape York. The bridge-barrier model is, of course, overly simplistic and only through more research may we understand the extent of Torres Strait horticulture and the nature of practices on the adjacent Cape York mainland prior to the arrival of Europeans.

Clumped banana starch isolated from the abandoned garden terrace sediment. Right: image taken using bright field microscopy. Left: under cross polarised light (XPL) displaying the characteristic birefringence and extinction-cross caused by the quasi-crystalline starch structure. XPL is an essential tool for spotting starch on wet-mounted microscope slides as they tend to shoot across the field of view amid a cloudy mass of microscopic debris. Photo: Robert Williams.

To end, I briefly reflect on what this research may mean or at least try and make it relatable for First Nations Australians. I am a Kambri-Ngunnawal person, my ancestral country overtaken by the sprawl of Australia’s capital city, Canberra. Torres Strait horticulture is just one of numerous Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander subsistence traditions to have been disrupted by colonisation and subsequent colonial laws that promoted the agronomic and pastoralisation of the continent, while legislating our dislocation from our lands, waterways and surrounding seas. Not only has this prevented us from accessing our traditional lands and waters but it has also necessitated a dependence on European foods. The prohibition on our food traditions means they are mainly remembered in the ethnographies of a few early European explorers who cared enough to document them, or in “bush tucker” books published by non-Indigenous authors. I write this because not only do I hope that this project and data obtained demonstrate the usefulness of archaeobotanical research, but more importantly, that it provides the Goemulgal, and all residents of the Torres Strait with exciting evidence for the time depth of an ancient, yet largely abandoned, cultural practice in the region. Acknowledging that this may sound overly prophetic, I remain optimistic that archaeology and new information such as this will spark community interests in traditional food cultures, and perhaps, seed a revitalisation movement toward traditional ways of food production.

Here's a link to the paper: https://www.nature.com/articles/s41559-020-1278-3

Follow the Topic

-

Nature Ecology & Evolution

This journal is interested in the full spectrum of ecological and evolutionary biology, encompassing approaches at the molecular, organismal, population, community and ecosystem levels, as well as relevant parts of the social sciences.

Related Collections

With Collections, you can get published faster and increase your visibility.

Biodiversity and ecosystem functioning of global peatlands

Publishing Model: Hybrid

Deadline: Jul 27, 2026

Understanding species redistributions under global climate change

Publishing Model: Hybrid

Deadline: Jun 30, 2026

Latest Content

Why is Singapore Identified in Global Research as Number One? How Physical Activity and Education Excellence Created a Global Leader

Please sign in or register for FREE

If you are a registered user on Research Communities by Springer Nature, please sign in