Sex and gender in COVID-19 research: Little progress on inclusion despite clear need

Published in Social Sciences and Sustainability

From the early stages of the COVID-19 pandemic there were many, and often conflicting, signals of sex and gender disparities. The likelihood of becoming infected, symptom severity and mortality all seemed to depend strongly on sex and gender, or on the complicated interplay of the two1. In addition, the social, economic and professional burdens of the pandemic seemed to be falling unequally on men and women2. Thus, starting already in the spring of 2020, we saw calls for researchers to incorporate sex and gender dimensions in COVID-19 research, both in traditional media and academic journals3,4,5,6.

Being already involved with research on the role of gender diversity in the inclusion of gender and sex analysis in clinical research, together with Sabine Oertelt-Prigione and Mathias Wullum Nielsen, we wondered whether trials conducted on coronavirus patients were responding to the calls and paying particular attention to these variables. We had a preliminary look at this in mid-2020; using the ClinicalTrials.gov repository we looked for mentions of ‘sex’ or ‘gender’ in the detailed description of the study protocol and found that COVID-19 studies were not much more likely to discuss these variables than were the overall cohort of studies registered in 2020.

We followed up on this in more detail in our paper which was published recently in Nature Communications. We looked into two different sources with information on clinical studies: the mainly US-based ClinicalTrials.gov (henceforth CT.gov) repository of clinical study registrations and the more globally oriented PubMed database of biomedical literature. Our CT.gov sample was comprised of ongoing (the majority being in the recruiting stage) as well as completed studies, with a main focus on COVID-19 and registered on CT.gov in 2020. These could range from clinical trials of vaccines and drug interventions to observational studies looking at seroprevalence in different populations, the effects of lockdown measures on mental health and access to healthcare and so on. Our PubMed sample consisted of result papers for randomized control trials (RCTs) of COVID-19 drug interventions published prior to December 15, 2020.

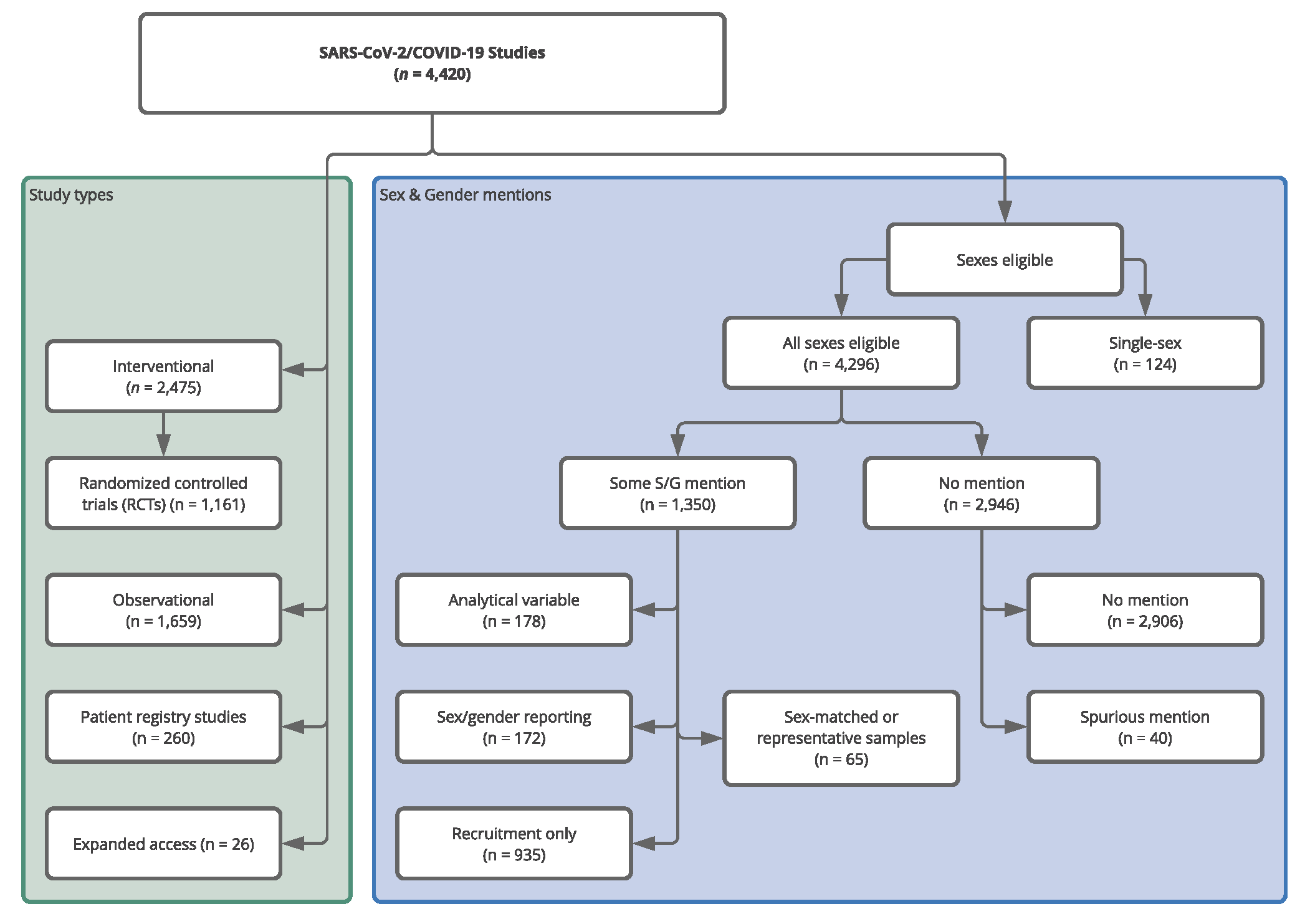

In both cases, the results were not impressive. Of the 4,420 COVID-19 studies we identified on CT.gov only 30.6% had any relevant mention of sex/gender at all in the study registration; ranging from a clear plan to analyze the variable (4%), to only aiming for a representative sample or sex-matched subgroups (5.4%) and finally, simply having a statement of intent to recruit all sexes/genders (and no consideration beyond that; 21.2%). In addition, only one trial explicitly addressed transgender people. One could argue that a lack of explicit attention to sex/gender in the study registrations is merely a signal of low adherence to detailed pre-registration conventions and does not necessarily translate into a true blindness to these important variables. Thus, we looked at a sample of published papers for drug RCTs, RCTs being commonly considered the ‘gold standard’ for evaluation of interventions. For these published trials, the results were slightly better. Out of the 45 trials, 8 (17.8%) reported sex-disaggregated analyses and 4 (9%) adjusted their analysis by sex/gender.

Study types and allocation into sex/gender (S/G) attention groups for the CT.gov COVID-19 sample. The left-hand (green) panel shows the distribution of the 4,420 identified studies across study types. We created the (Pharmacological) RCT label, the other classifications are taken from CT.gov. The right-hand panel (blue) shows the distribution of studies across the various mutually exclusive sex/gender groups we defined. In the ‘Some S/G mention’ set there is a hierarchy. The most extensive consideration was sex/gender as an analytical variable and after that sex/gender matching/representation, followed by explicit statements of intent to record or report participant sex/gender. Finally, the ‘Recruitment Only’ contains those studies whose only S/G mention was in a recruiting context. We allocated the studies to one of the categories based on the highest category of S/G consideration. For instance, if they reported attention to S/G in analysis and recruiting, we only counted them in analysis.

Why should this give us pause for thought? The striking differences in COVID-19 morbidity and mortality highlight the need for a universal consideration of these variables. Even though there were many calls throughout 2020 for sex and gender sensitive research, we found that the fraction of studies considering using sex/gender as an analytical variable from the early planning and registration stages remained fairly low throughout the year and did not improve significantly upon publication. Our CT.gov sample had a large fraction of observational studies (37.5%) who were more attentive to sex/gender in general; 6.8% of them planning an analysis vs 1.9% of the interventional studies (including RCTs). Although observational studies were generally larger and therefore better powered to incorporate sex and gender into their designs, we have seen that sex was a relevant factor in incidence of side effects in drug treatments and vaccines and thus cannot easily be dismissed as a variable in smaller interventional studies.

What can we learn from this? This pandemic has given us an excellent case study in how sex and gender (and their interplay with other socio-economic factors) influences all facets of a disease – exposure, adherence to pandemic prevention protocols, presentation of symptoms, access to healthcare and other support, severity of disease, mortality, response to drugs and vaccines, recovery trajectories and so on – and how such an information gap could lead to tragic outcomes and misallocation of limited resources. We would argue that sex/gender needs to be incorporated at all levels of clinical research as a matter of course, from the earliest recruiting stages to final data analysis and detailed reporting of sex-disaggregated data (even in the case of trials are not statistically powered to disaggregate results by sex, the research community could be well served by making sex-disaggregated data publicly available for pooling in evidence synthesis). Better enforcement of detailed pre-registration of analysis protocols, study designs and post-completion reporting of data could aid this effort, as well as better inform the public and the scientific community.

However, we also believe in the need to facilitate an ongoing discussion of the importance of including sex and gender in medical research if guidelines are going to be translated into action, rather than hoping it will apply itself if the proper, well-meaning regulations and policies are in place. A pandemic with such a disruptive force as COVID-19 has had, will of course challenge our systems and modus operandi. But considering the differences in sex and gender of patients should not just be something we do because a policy or rule requires it, it is something we should do because it is clinically meaningful. And this does not just go for COVID-19 either, but for the vast majority of clinical research, where physiological sex differences can affect the outcomes of treatment and gender affect the access to care and exposure to infection.

Poster image: Simon Andersen Nørredam, Aarhus BSS, Aarhus University.

References:

- Abate BB, Kassie AM, Kassaw MW, et al. Sex difference in coronavirus disease (COVID-19): a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Open 2020;10:e040129. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2020-040129 (2020)

- Wenham, C. et al. Women are most affected by pandemics — lessons from past outbreaks. Nature 583, 194-198, doi: 10.1038/d41586-020-02006-z (2020)

- Wenham, C., Smith, J., Morgan, R., Gender & Group, C.-W. COVID-19: the gendered impacts of the outbreak. Lancet 395, 846-848, doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30526-2 (2020)

- Bischof, E. et al. Towards Precision Medicine: Inclusion of Sex and Gender Aspects in COVID-19 Clinical Studies-Acting Now before It Is Too Late-A Joint Call for Action. Int J Environ Res Public Health 17, doi:10.3390/ijerph17103715 (2020)

- Spagnolo, P. A., Manson, J. E. & Joffe, H. Sex and Gender Differences in Health: What the COVID-19 Pandemic Can Teach Us. Ann Intern Med 173, 385-386, doi:10.7326/M20-1941 (2020)

- Shattuck-Heidorn, H., Reiches, M. W. and Richardson S. S., What’s Really Behind the Gender Gap in Covid-19 Deaths? New York Times, June 24, 2020.

Follow the Topic

-

Nature Communications

An open access, multidisciplinary journal dedicated to publishing high-quality research in all areas of the biological, health, physical, chemical and Earth sciences.

Related Collections

With Collections, you can get published faster and increase your visibility.

Women's Health

Publishing Model: Hybrid

Deadline: Ongoing

Advances in neurodegenerative diseases

Publishing Model: Hybrid

Deadline: Mar 24, 2026

Please sign in or register for FREE

If you are a registered user on Research Communities by Springer Nature, please sign in