Shipping and other loud sounds in Arctic waters – Adapting future underwater noise regulations to polar waters and polar seasons

Published in Bioengineering & Biotechnology and Earth & Environment

Ever lived next to a busy road? Then you know how disruptive it can be: heavy traffic at rush hour, loud motorbikes in the middle of the night, rumbling trucks and blaring car stereos. Constant exposure to sound is a health risk, apart from being a real nuisance. And the same goes for animals.

I remember my first field trip to the Arctic, dipping a hydrophone in Kongsfjord (Svalbard) and hearing the sound of melting ice, the vocalisation of the whale who was checking us out (and particularly this long cable dangling from a small, stationary boat) … and then the noise of rain falling all around us … and then the sounds from a ship many kilometres away, far away in the gathering clouds … All these sounds combine to create an ever-changing soundscape, varying with time and with seasons …

How do soundscapes evolve? When we monitor possible impacts on animals, should we account for the changes in seasons, as the polar ocean is sometimes covered with ice and sometimes completely open? As human activities increase across the Arctic, it is important to compare what the sounds are now (the baseline) to how they might change (louder? louder only at some frequencies? not loud enough to affect animals?). This is where setting up evidence-based guidelines is important.

In the European Union, the Marine Strategy Framework Directive is using “shipping bands”, third-octave bands centred on 63 Hz and 125 Hz. How loud the sounds are in these bands is used to define baselines for “Good Environmental Status” and assess when this becomes too loud. This is of course based on measurements, in many different areas around Europe and over different seasons and years. In places where there are not enough measurements, acoustic models use the satellite recording of ship tracks to quantify the sounds they create in these frequency bands. This allows simulating future evolutions, for example a new shipping route or denser traffic, changes in ship types, the impacts of resource exploitation and tourism. But how does it work in polar regions?

In early measurements, we realised sounds could be louder in these “shipping bands” in winter, when the sea is covered with ice and there are no ships. But how common is it? How loud is that, when looking at scales of weeks, months and years? And what creates these loud sounds? How many of them are natural sounds, like ice cracking or animal vocalisations, and how many come from human activities?

In our 2026 npj Acoustics article, we have used high-fidelity, continuous measurements of the sounds in Cambridge Bay (Nunavut, Canada), acquired by Ocean Networks Canada between 2015 and 2024. We focused our studies on the months of May (full ice cover, no shipping) and August (little to no ice, shipping activity) and we analysed the sounds loud enough (> 10 dB above weekly background) for long enough (> 1 minute), identifying where they came from and what frequencies they extended into.

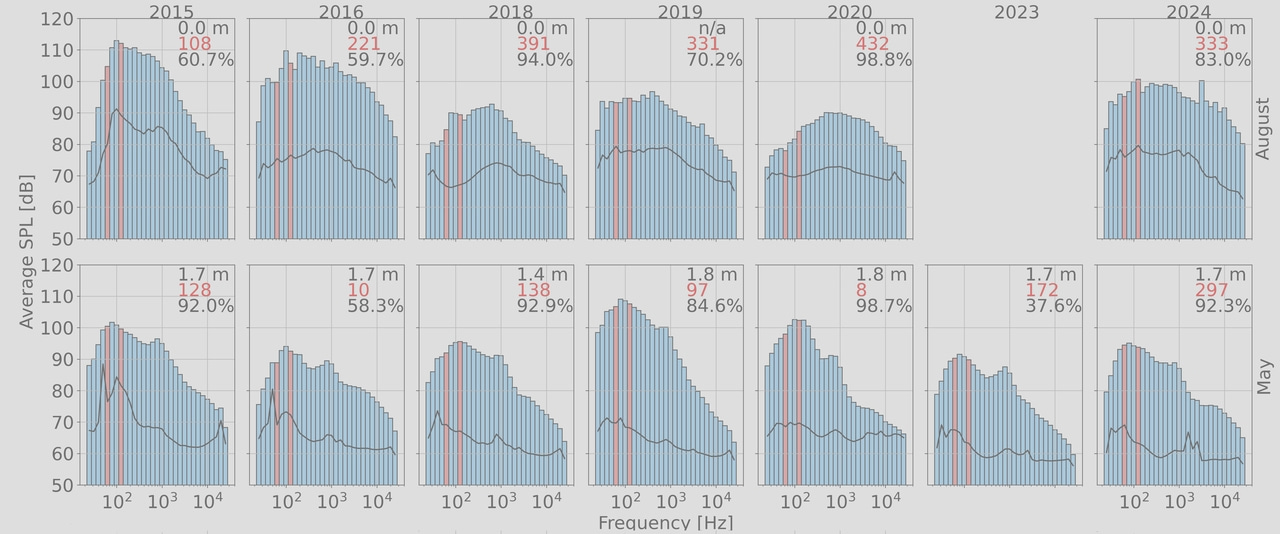

The poster image shows part of our results. For either summer or winter of every year between 2015 and 2024, we show the Sound Pressure Levels in each third-octave band (in blue) and highlight the “shipping bands” in red. We added information about ice draft above the hydrophone (in metres), the number of loud, continuous events identified (in red) and the number of measurements available for the month. For example, for August 2015, the mean ice draft was 0.0 m and there were 108 loud, continuous events identified in measurements covering 60.7% of the entire month. Conversely, for May 2015, the mean ice draft was 1.7 m and 128 loud, continuous events were identified in measurements covering 92.0% of the entire month.

Surprisingly, we heard a lot of noise from other human sources than ships: low-flying aircraft, snowmobiles, machinery (onshore or on the ice). These are human sounds, and they should be part of future, polar regulations of underwater noise in the same way that shipping is.

The poster image shows the “shipping band” can be equally loud in both open-water and ice-covered months. In summer, levels in the 63-Hz are generally lower than in the 125-Hz band, an observation often made when smaller vessels are present. In winter, both bands are at generally similar levels. Year-to-year variations do not show any particular trend, in particular from climate change effects.

The MSFD “shipping bands” are therefore not perfect in polar environments. The frequencies of loud events extend well above 1 kHz in open-water season whereas they do not extend beyond 1 kHz at the maximum extent of ice cover. These variations also affect the baseline levels for human impacts, which might vary with the months (or with the seasons). Future polar regulations should therefore extend to higher frequencies and they should account for the amount of ice cover.

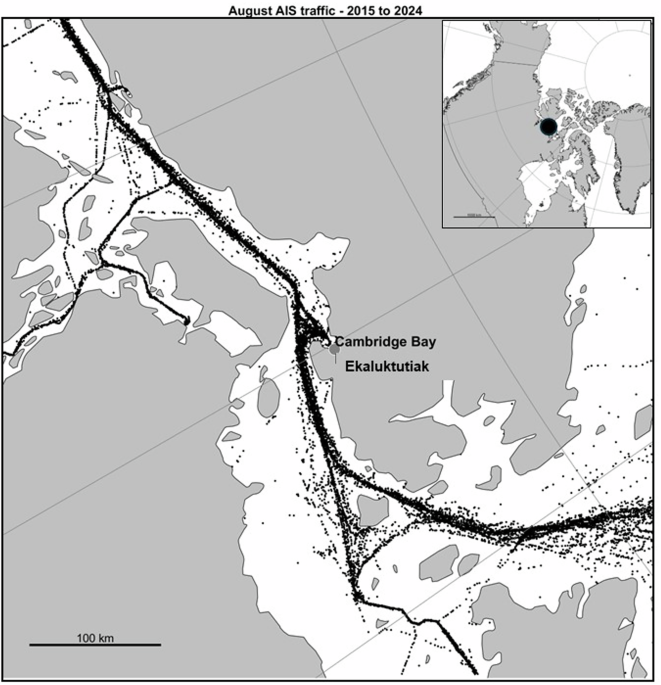

Large vessels are tracked by satellite using their Automatic Identification Systems (AIS), and this is used in models of ship noise, to simulate future evolutions or to fill gaps in measurements. AIS is not compulsory (and not used) on smaller vessels, and evidence from other oceans shows that, in some cases, they get switched off, for example to mask illegal fishing or other activities. This does not seem to be an issue in the Arctic, at least at the moment, but our results show that AIS are not enough to understand shipping. In summer, more ships can be heard than are tracked by AIS. In winter, the absence of ships does not preclude important soundscape contributions from other vehicles like snowmobiles. Satellite records of shipping (using AIS) are not enough to assess and/or model human contributions to underwater soundscapes.

The European Marine Strategy Framework Directive and its criteria for Good Environmental Status (related to third-octave bands centred on 63 Hz and 125 Hz) are very good examples of how to monitor and ultimately manage anthropogenic impacts on underwater soundscapes. But they are not adapted to Arctic conditions like in the shallow-water environment of Cambridge Bay. Any guidelines to be developed for and used in polar regions, need to address the presence of ice, its thickness and extent, with distinct assessments depending on the seasons. These guidelines need to incorporate the contribution of smaller vessels and other sources of sounds like snowmobiles on ice. The results from Cambridge Bay show for example that frequencies should be considered well above 1 kHz in open-water season but below 1 kHz at the maximum extent of ice cover.

Arctic experts like Halliday et al. (2020) concur that ambient sound levels in the Arctic seas are currently very low, and that marine life will therefore be more sensitive to any increase. The effort to “go beyond the shipping bands” and define adequate baselines is particularly pressing as climate change and geopolitical challenges are bound to greatly increase access to the Arctic and its marine (and terrestrial) resources. The measurements we present here need extending to other Arctic environments, from the High Arctic to transcontinental shipping lanes and coastal communities, with variable ice cover and other sound sources. It is therefore increasingly urgent to define an “Arctic Marine Strategy Framework Directive”, and our article shows how loud events can be analysed and help define these future guidelines.

Follow the Topic

-

npj Acoustics

npj Acoustics considers research relating to the discipline of acoustics. Important areas of interest are the generation, propagation, sensing, manipulation, and perception of sound and the analysis of related acoustic phenomena.

Please sign in or register for FREE

If you are a registered user on Research Communities by Springer Nature, please sign in