“Show me someone without an ego, and I’ll show you a loser”

Published in Social Sciences

By Joël van der Weele and Peter Schwardmann

The quote in the title is from the current President of the United States (Twitter, July 19, 2012) and seems to epitomize his social behavior; to overwhelm others with his grandiose sense of self-worth. Many self-help books also advocate for the power of self-confidence, albeit in a more gentle and diplomatic way: If you only believe in yourself, success and social rewards will be yours.

Probably unbeknownst to him, Trump’s tweet has serious theoretical underpinnings. In various articles written since the 1980’s, the evolutionary biologist Robert Trivers hypothesizes that our delusions, such as an inflated ego, serve a social purpose. Truly believing in something or someone (yourself), makes it easier to convince others and persuade them to invest in this cause. Following George Costanza’s maxim "It’s not a lie if you believe it", self-deception obviates the need for lying, reduces give-away tells and makes you more persuasive.

The crucial element of this theory is that people truly believe their self-deceptions. In a recent article, social psychologist Bill Von Hippel and Trivers make the case for their social theory of self-deception, but acknowledge that "no one has examined whether self-deception is more likely when people attempt to deceive others.'' (2011, p.12). Indeed, the empirical evidence is scant. Self-help books mostly rely on anecdotal evidence and individual success stories. Of course, Trump did become president, but who knows what he really believes? Studies also show that people who express more confidence are perceived as more impressive, but again, these might be cases of conmanship rather than self-deception.

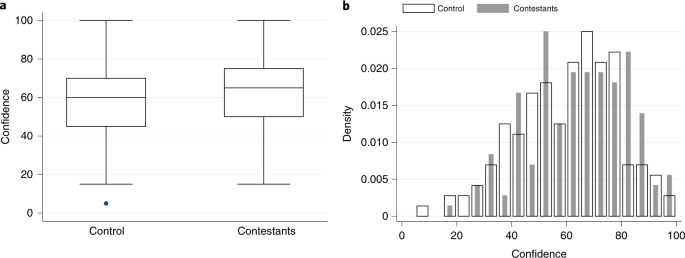

Thus, Von Hippel and Trivers issued a call to arms, and both authors of this post independently set out to design an experiment to test whether a) higher confidence in one’s own competence helps to secure better evaluations from others and b) people do in fact manage their private beliefs to exploit these social gains. A major challenge is to measure true beliefs. To do so, we proposed using techniques from experimental economics: by letting subjects bet on their own performance on an intellectual test, they have money at stake for reporting their accurate beliefs. Similarly, we incentivized the evaluators to bet on who actually performed well, giving them a stake in detecting true performance.

In the end, our projects merged thanks to Jeroen van de Ven, a mutual friend and academic working on similar topics, who proposed a match after hearing our individual plans. The resulting paper, which has just been published and which you can read here, shows confirmatory evidence on both research questions. We find causal evidence that confidence about performance on an intelligence test helps one convince others. Confident subjects are more persuasive through both verbal and non-verbal channels. Furthermore, people become more confident when they are told that they have an opportunity to make money from persuading others. In the meantime, several other papers and preprints, some of them by Trivers and Von Hippel together with other co-authors, show results going in the same direction.

We think that this strand of research demonstrates something deep about human cognition, and overconfidence in particular. Overconfidence has often been described as a “bias” or a mistake, but is simultaneously recognized as deeply human. According to Daniel Kahneman overconfidence “is built so deeply into the structure of the mind that you couldn’t change it without changing many other things.” Our research suggests why: some overconfidence may in fact be good for you. It helps you to make the case for yourself more persuasively.

Boundless overconfidence is probably not a good thing, as Donald Trump’s billion dollar losses as a businessman demonstrate. Evolution has equipped most of us with the cognitive technology to strike a balance between making realistic decisions and adapting to our social environment that values confidence. The outcome of that balancing act does not appear to be perfect realism.

Follow the Topic

-

Nature Human Behaviour

Drawing from a broad spectrum of social, biological, health, and physical science disciplines, this journal publishes research of outstanding significance into any aspect of individual or collective human behaviour.

Please sign in or register for FREE

If you are a registered user on Research Communities by Springer Nature, please sign in

Cool article - thanks! I wonder, is there a relationship between this phenomenon and that described by Dunning & Kruger (re: actual competence and self-assessed competence)?

Some of the overconfident people might posing overconfident...!