Simulation of group selection models

Published in Ecology & Evolution

Public significance

The paper seeks to resolve a widespread confusion over whether group selection can override individual selection. The paper uses detailed simulations to find the limits of parameter values that allow group selection to prevail. Several different mechanisms of group selection are simulated, including a new model with floating group territories.

History of the theory

The first time I read about group selection was in Wilson’s book Sociobiology from 1975. Wilson believed that group selection through warfare could explain the evolution of conformity and the capacity for culture in humans. Whereas Wilson’s theory was very superficial, Boorman and Levitt devoted a whole book to detailed mathematical models of group selection in 1980, but I found their models too abstract to be realistic. A pioneering simulation study by Levin and Kilmer from 1974 was actually more realistic.

Group selection has been hotly debated for many years. Many theorists were skeptical about group selection, but the theory got renewed interest in 1981 when Jarvis reported the discovery that a mammal – the naked mole rat – had a social organization very similar to the social insects such as bees, ants, and termites.

An article in Nature in 2010 claimed to explain how sociality can evolve in insects without the need for kin selection or group selection. It claimed that a mutation that made a female worker stay in the nest also prevented her from reproducing. This article was heavily criticized by many scientists who found logical flaws in the article and argued against the discreditation of kin selection. A more plausible explanation of insect sociality is that the queen’s offspring actively prevent other females from reproducing in competition with their mother (link).

Several lines of research have produced different types of mathematical models of group selection. Some of the more recent models are less realistic than previous models. They have made many simplifications and unrealistic assumptions in order to fit particular mathematical methods. This includes the Moran models and game theory models.

I was very surprised by the survey published in 2023 finding that many anthropologists and psychologists believe that group selection has contributed to human evolution, even though all quantitative models conclude the opposite.

I have tried to clear up the confusion by making my simulation study so comprehensive and so detailed that it can give more reliable and convincing answers to questions about group selection.

Simulation experiments

I started my computer simulation experiments back in the late 1980s and kept working on this project on and off until the beginning of the 2000s. I did not make a detailed report of the results at that time, but only a brief publication in 2000 that focused more on the software than on the results. After I retired in 2024, I finally got time to finish this project.

Previous quantitative studies mostly relied on some variant of an island model where groups live separately on each their “island”. These mathematical models relied on many simplifying assumptions. My simulation study is more comprehensive. It covers many different possible mechanisms of group selection including a new model based on floating group territories. This new model is more realistic than the traditional island models for simulating group selection in humans (and chimpanzees). I have varied all parameters in order to investigate how they influence the results. This work concludes with detailed maps of which parameter ranges allow group selection to override individual selection, and which values do not. Nobody else has done this.

Simulation videos

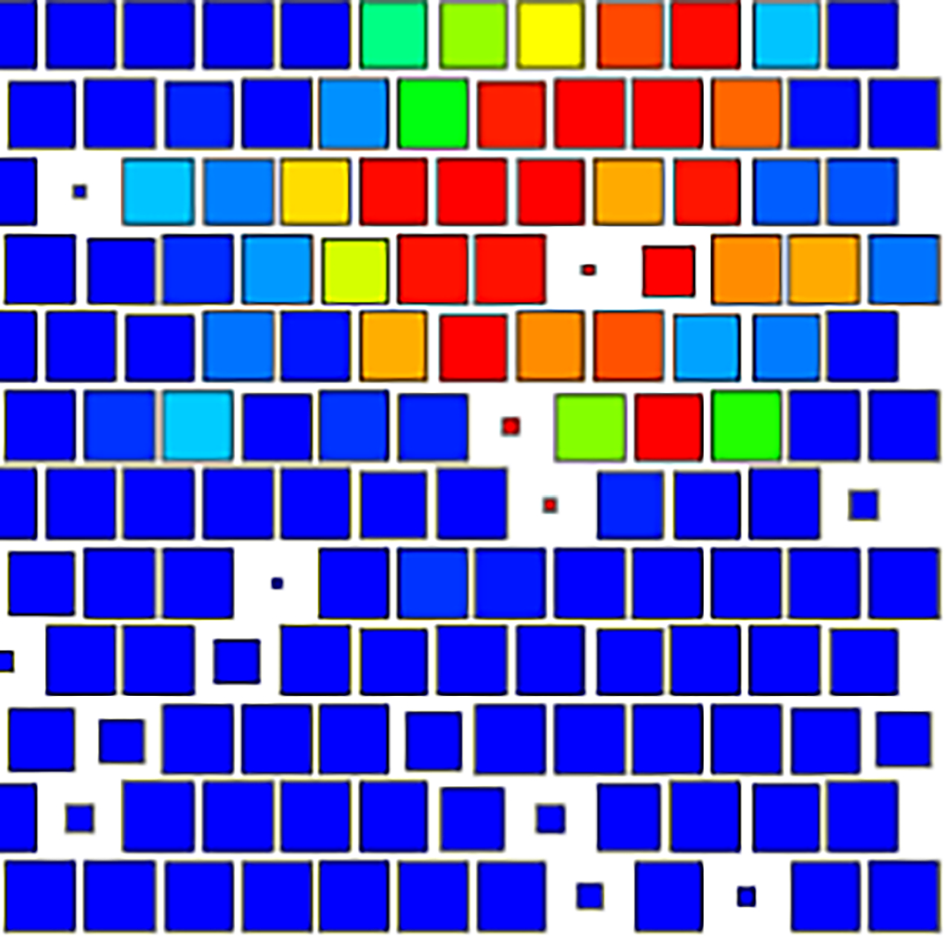

The first video shows a time lapse of the simulated evolution of eusociality in insects according to the outsider exclusion model. Black squares indicate nests without eusociality. Blue squares represent nests where the outsider exclusion gene is common. Red squares represent the altruism gene. Purple squares represent nests where both the outsider exclusion gene and the altruism gene are common. Intermediate colors indicate mixed populations. Old colonies die at a rate that is lower when altruism is common than when it is not. The space left by dead colonies allows new nests to be built by members of a nearby colony. Small squares are newly formed nests. They grow to their maximum size in the course of a few generations.

The altruism gene (red) arises from time to time due to mutation and genetic drift, but it disappears again because individual selection favors egoism. The gene for outsider exclusion (blue) can spread as soon as it has reached a critical concentration by chance. This can be seen as an increasing number of blue squares. The outsider exclusion gene makes the conditions more favorable for the altruism gene by preventing immigration of egoist individuals. The altruism gene starts to spread more widely only in areas where the outsider exclusion gene is already common. This is seen by the purple squares, indicating both outsider exclusion and altruism.

The second video shows how the model with group territories works. Again, we see a time lapse of simulated evolution. Each group has a territory whith an irregular shape. Blue territories represent a population without the altruism gene. Red territories are inhabited by individuals with the altruism gene. Intermediate colors represent mixed populations. Altruists are willing to fight for their group in territorial wars, while egoists are not. The more altruists there are in a group, and the larger the group, the higher its military strength. Stronger groups can conquer a piece of territory from weaker neighbor groups. Altruism arises in one group due to mutation and genetic drift. This group starts to conquer more and more territory from neighbor groups. After it has reached a certain size, it splits into two groups that both continue to grow. When a group splits in two, the two daughter groups sometimes have different proportions of altruists due to random genetic drift. This generates a difference in strength where the groups with the highest proportion of altruists grow more, at the cost of neighbor groups with fewer altruists. After many generations, we end up with more and more groups with only altruists (red). Egoism can reappear due to mutation and drift, but it is eliminated again by surrounding altruist groups.

I must emphasize that the latter video does not represent a realistic explanation for the evolution of territorial warfare. The parameters in the simulation model have been set to unrealistic values in order to make the mechanism work. The purpose of showing this simulation is not to postulate that group selection has affected human evolution, but to illustrate how the tested model works. This model is more realistic and more effective than previous models, yet it is still not strong enough to explain the evolution of warfare or altruism in humans under realistic conditions.

Conclusion

The paper delivers reliable answers to the much-debated questions of group selection. The conclusion is that warfare or altruism could not have evolved in humans by genetic group selection alone. Other mechanisms including cultural evolution, leadership, reward, and punishment have no doubt played important roles. A future publication will describe an extension of the group territoriality model where the evolution of leadership plays a crucial role, as predicted by regality theory.

Cover photo: Naked mole rat colony ©Shutterstock

Follow the Topic

-

Bulletin of Mathematical Biology

This journal shares research at the biology-mathematics interface. It publishes original research, mathematical biology education, reviews, commentaries, and perspectives.

Please sign in or register for FREE

If you are a registered user on Research Communities by Springer Nature, please sign in