Social Class Linked to Collectivism in Rice Cultures

Psychologists have linked social class to individualism, which fits with the idea that money frees people from having to rely on others. But a new study finds this link flips in rice-farming cultures.

Published in Social Sciences, Agricultural & Food Science, and Behavioural Sciences & Psychology

Researchers have found through several studies that people of higher social status tend to be more individualistic and think more analytically. That includes my own research, as well. But a new study from my research team finds this pattern flips in cultures with a history of rice farming.

The idea that social class makes people individualistic has a logical story behind it. The idea is simple. Wealth and power give people the freedom to do what they want. They don't have to rely on other people.

Notice that this is a general, abstract story. In other words, it should be generally true.

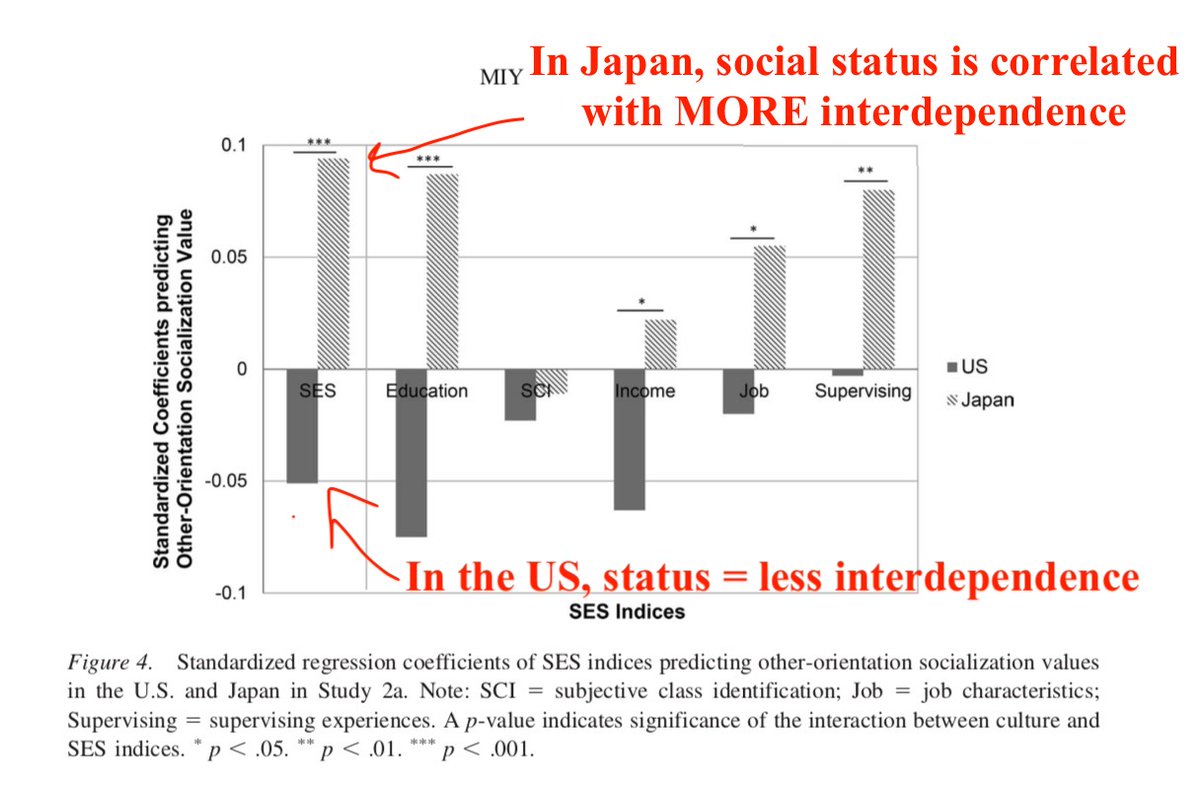

However, when researchers tested this in Japan, they found the opposite pattern from the US. People from higher social classes were more interdependent.

Why would the pattern flip in Japan? We suspected it might have to do with Japan's history of rice farming. Rice farming required twice the labor as grain crops like wheat and corn. This encouraged the formation of cooperative labor exchanges.

Rice also depended on complex irrigation networks. These networks required farmers to coordinate their water use and the maintenance, like dredging the canals. In sum, rice-farming areas are traditionally more interdependent, wheat-farming areas more independent.

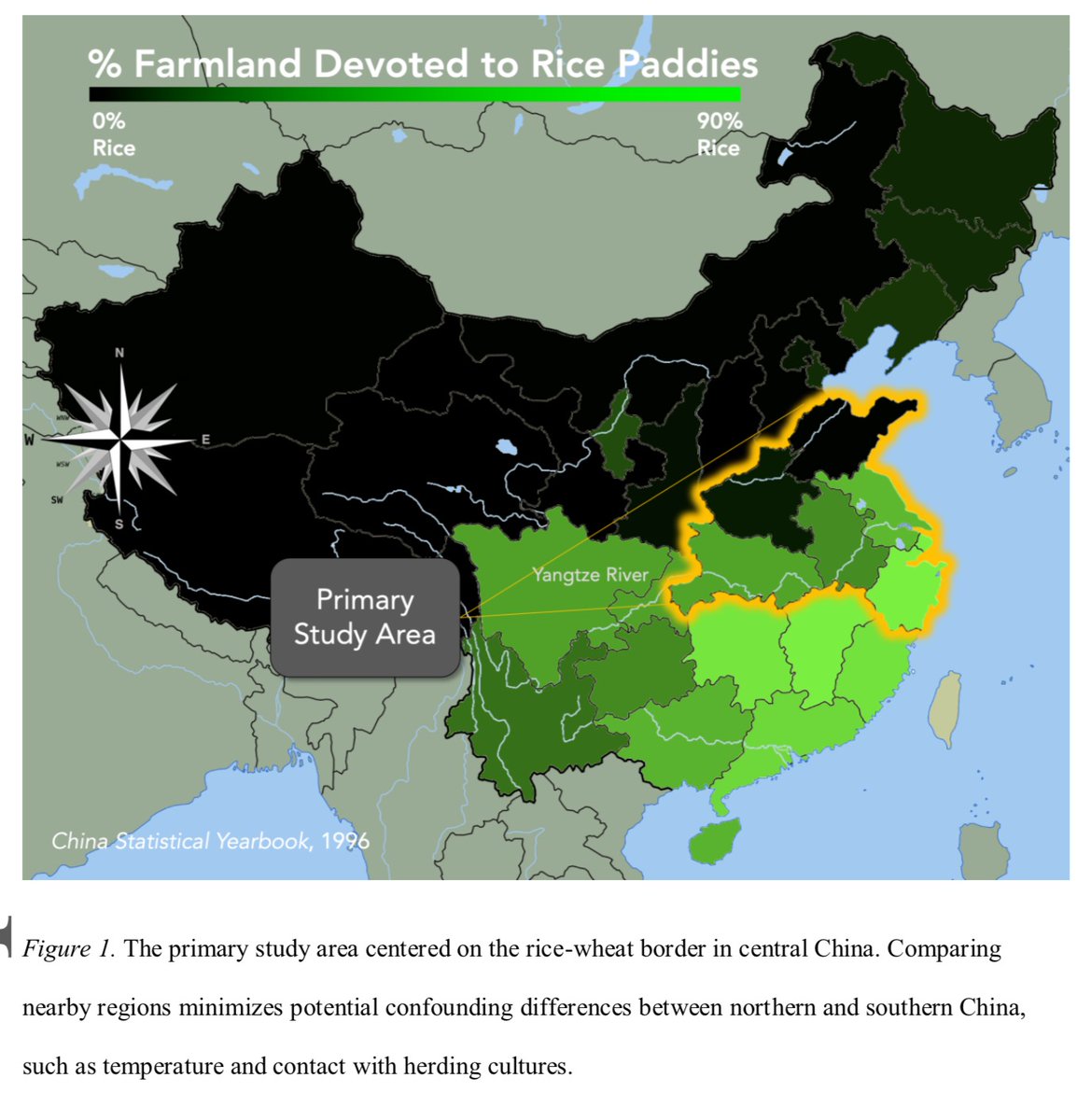

To truly test whether rice farming is a plausible cause of cultural differences, we needed a comparison group. Fortunately, China has different regions with histories of rice farming and wheat farming. We focused on people in nearby counties along the rice-wheat border in China.

Measuring Cultural Differences

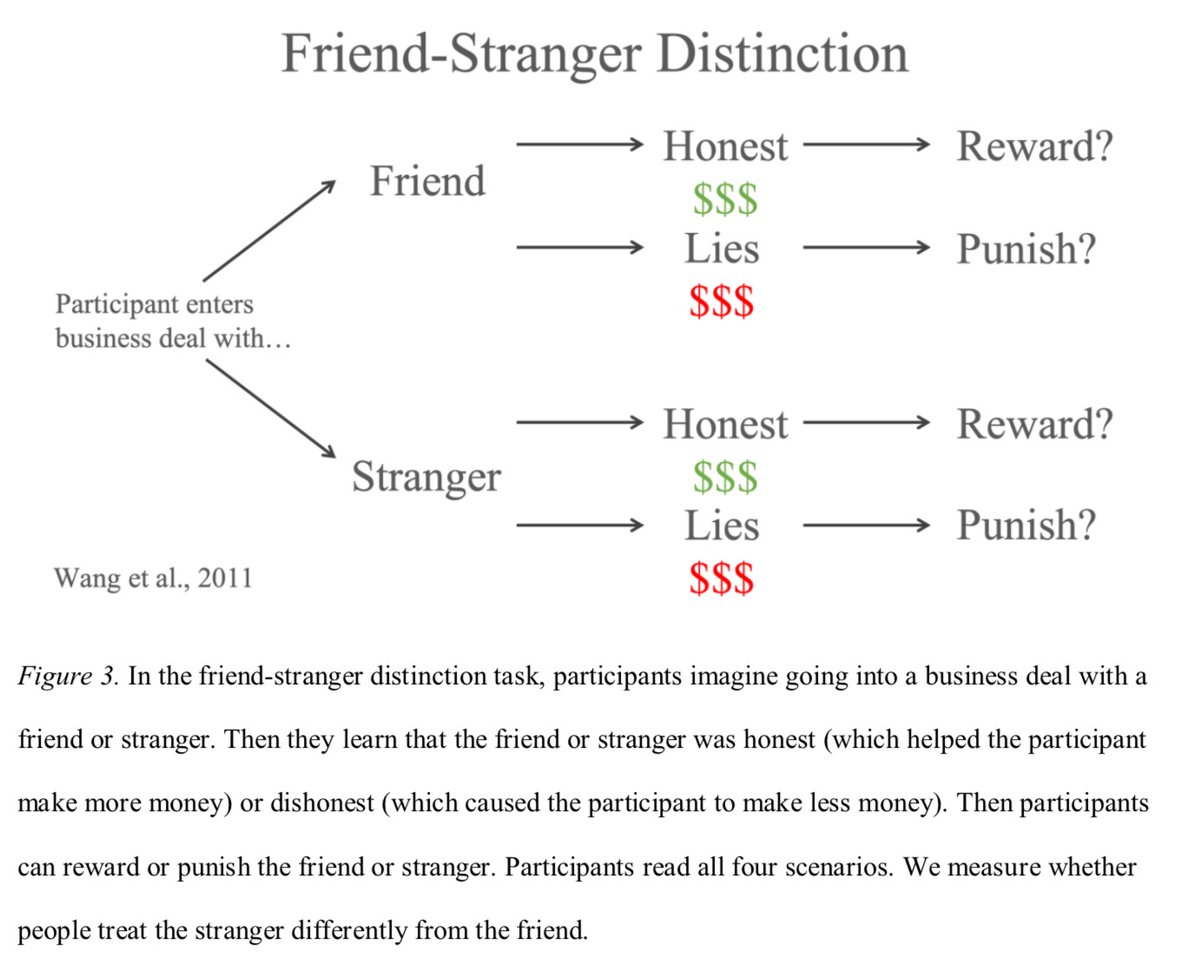

Psychologists have measured individualism versus interdependence in several ways. One way is the friend-stranger distinction. Interdependent cultures tend to draw a sharp distinction between friends and strangers.

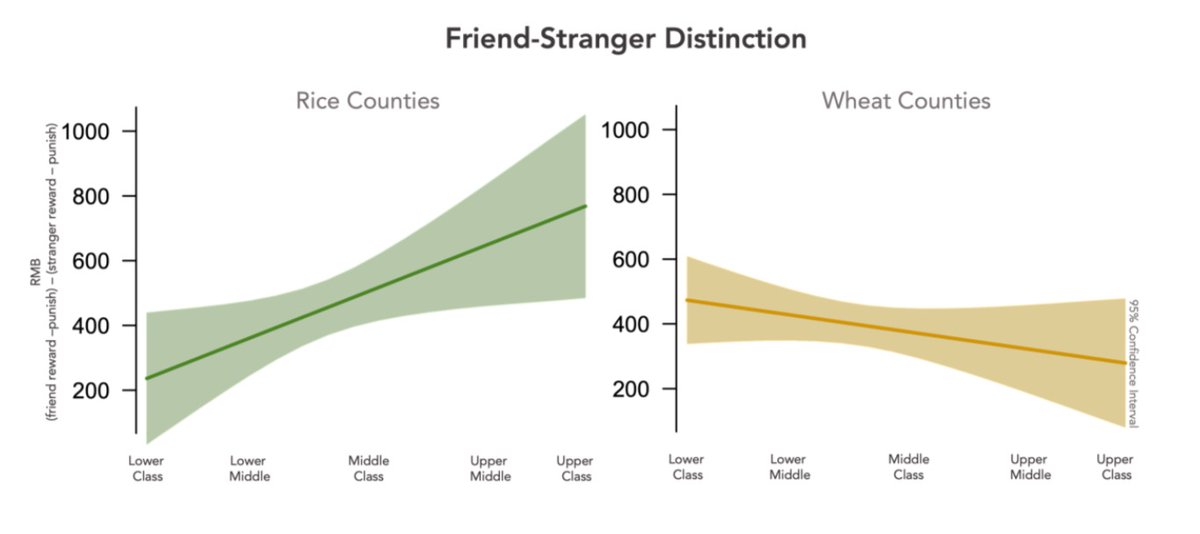

In rice counties, high-status people drew a bigger distinction between friends and strangers. In wheat counties, it trended the opposite way. In other words, the psychological correlates of social class were different in cultures with a history of rice farming versus wheat farming.

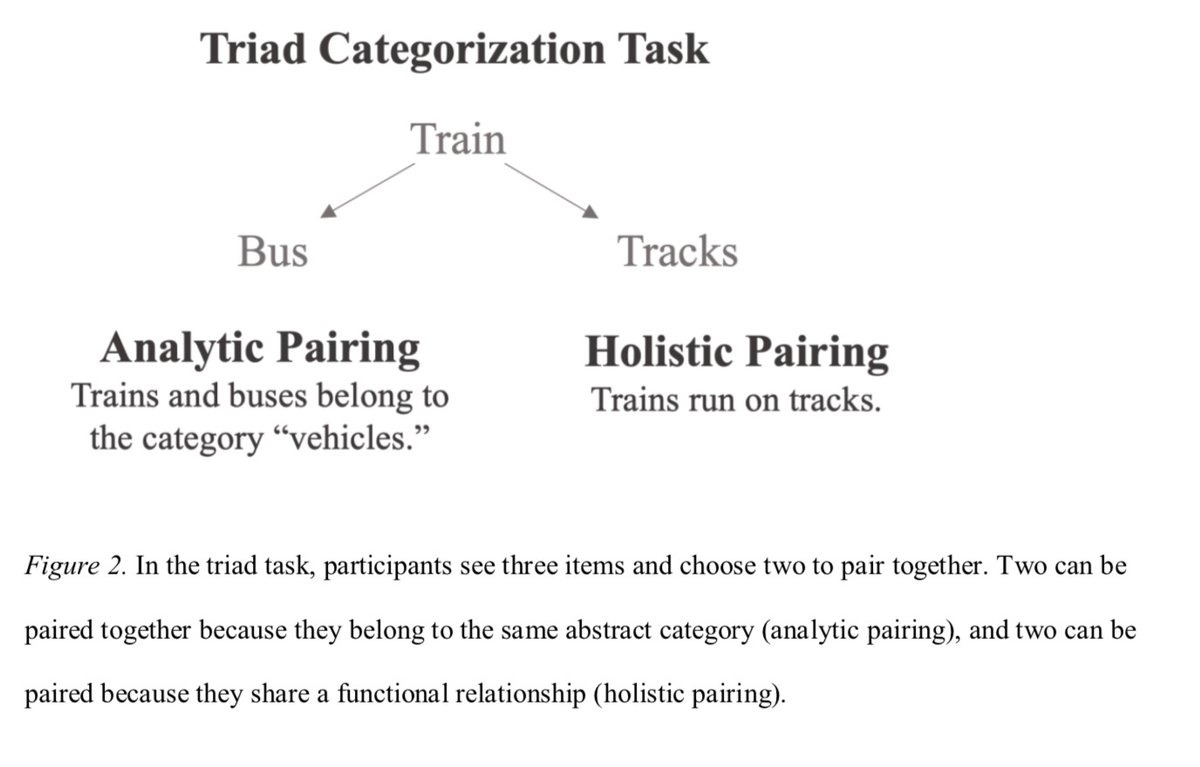

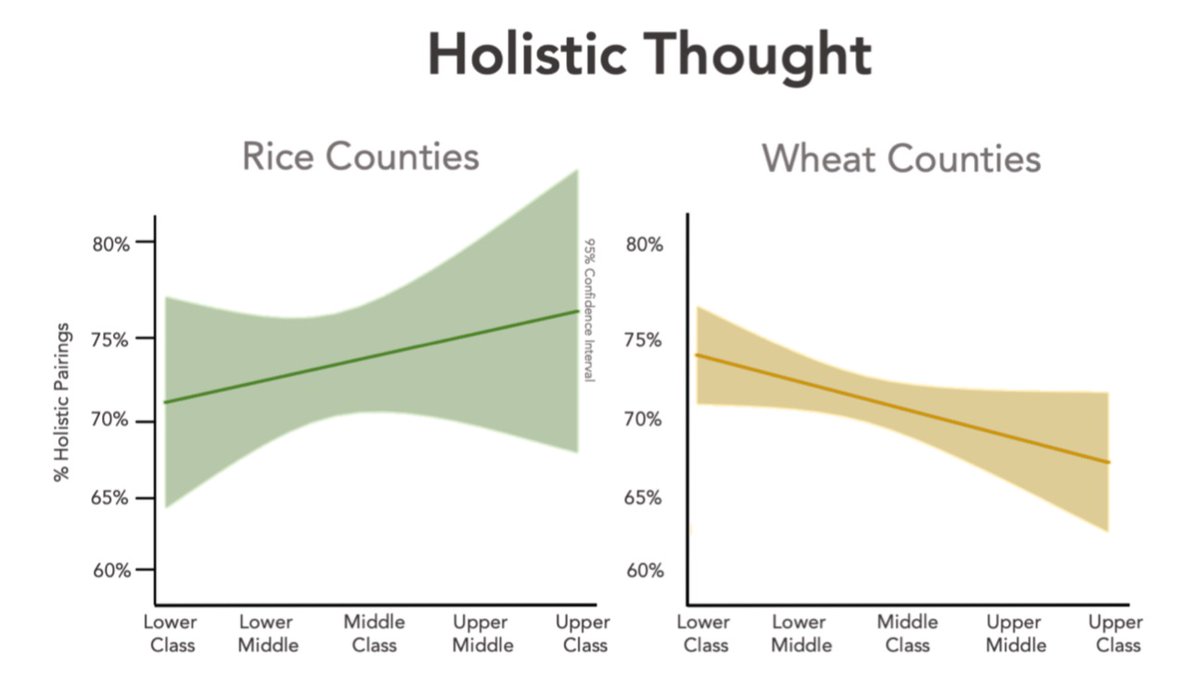

Another cultural trait psychologists measure is holistic thought. Holistic thought focuses on relationships between objects and the context. It tends to be more common in cultures in East Asia.

This is in contrast to analytic thought, which focuses on the characteristics of objects isolated from the context (much like how scientists run experiments in test tubes and stainless steel boxes to get rid of environmental effects). Analytic thought tends to be more common in Western cultures.

One way cultural psychologists have measured holistic versus analytic thought is by asking people to categorize objects. In the categorization task, people see three words, such as train, bus, tracks. They choose two to categorize together. Two words belong to the same abstract category, such as train and bus. Two share a functional relationship, such as train and tracks.

We gave the triad task to people in rice areas and wheat areas along China's farming border. In rice areas, high-status people tended to think more holistically, choosing more relational pairings. In wheat areas, high-status people tended to think less holistically, similar to findings in the US.

Whose Status?

What this all means is that social class differences in people's psychologies is not some abstract law. The basic idea that money buys freedom and therefore a Western style individualism is wrong. Instead, the effect of social class depends on culture.

Why does social class differ in rice-farming cultures? One idea is that interdependent rice cultures reward people who fit their cultural ideals, like prioritizing friends and relationships. The people who fit closer to the cultural ideal gain more status.

Another idea is that cultures give us scripts for how to use power and status. In the US, these scripts might tell people to focus on themselves (like the phrase, "you do you"). In rice-farming cultures, those scripts might focus on being enmeshed with other people, rather than separating from them. At the very least, this research suggests that we need to be careful about forming general, physics-like theories of human psychology based on studies that are largely done in the West.

Follow the Topic

Cognitive Psychology

Humanities and Social Sciences > Behavioral Sciences and Psychology > Cognitive Psychology

Social Psychology

Humanities and Social Sciences > Behavioral Sciences and Psychology > Social Psychology

Anthropology

Humanities and Social Sciences > Society > Anthropology

Agriculture

Life Sciences > Biological Sciences > Agriculture

History of China

Humanities and Social Sciences > History > Asian History > History of China

Asian Culture

Humanities and Social Sciences > Cultural Studies > Regional Cultural Studies > Asian Culture

Ask the Editor – Collective decision-making

Got a question for the editor about Experimental Psychology and Social Psychology? Ask it here!

Continue reading announcement

Please sign in or register for FREE

If you are a registered user on Research Communities by Springer Nature, please sign in