Social support and stress hormones in wild African elephant orphans

Published in Ecology & Evolution

The first time I observed the African elephants of Samburu and Buffalo Springs Reserves of Kenya was in 2015 with my PhD advisor, Dr. George Wittemyer, his PhD student at the time, now Dr. Shifra Goldenberg, and Save the Elephants’ long-term monitoring researcher, David (“Davido”) Letitiya. We sat on the dirt track in a research vehicle whose engine was off in the middle of a feeding herd near the Ewaso N’giro River. I was astonished at how calm the elephants were. In the years since 1998, these individually known elephants had become habituated to research vehicles and were totally unbothered by us.

From that very first day, and during the many hours I would spend watching elephants thereafter, one thing was certain: family, to elephants, is everything. An adult female passed behind her sister, rubbing against her in a behavior called a “body rub” and emitting a low rumble in greeting. An older sibling checked with her trunk what her little brother was eating, while a couple of cousins intertwined trunks or threw their front legs over one another’s backs in play.

Most of all, calves stayed near to Mom. They were never far from her. One curious calf lagged behind her mother by 10 – 15 meters among her siblings and aunts to smell the vehicle. Her mother moved to the other side of us where the calf could not see her. The calf cried out, and it was a beautiful thing to witness how quickly her mother stopped and ran back, tail slightly up and ears folding out and flopping, to reassure her baby.

George and others of Save the Elephants had observed such interactions for years, and he and Shifra conceived of an important suite of studies because they recognized that when an elephant is killed by humans, the story does not end. All the elephants with which he or she had a social bond are affected, meaning that people were not grasping the total impact of ivory poaching. It was time tell the rest of the story.

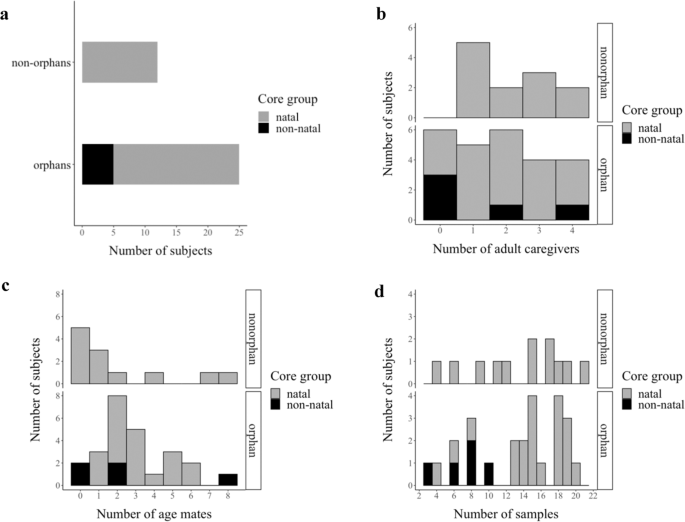

Shifra began her PhD working on the social consequences for elephant orphans, who in this population were orphaned during a period of drought and increased poaching from 2009 – 2013. She found that without their mother orphan elephants receive more aggression from other elephants than nonorphans, especially if they go to live with a different and unrelated family following their mother’s death. She also found that orphans interact less with knowledgeable adult females like matriarchs, instead strengthening their bonds with elephants of the same age.

My PhD research built on this base by looking at the physiological consequences of being orphaned. Using years of long-term demographic data, we discovered that orphan elephants suffer lower survival even if they are weaned when their mother dies, and that the death of orphans measurably depresses population growth. We continued on to investigate the physiology of orphans who managed to survive.

After collecting hundreds of dung samples from known orphans and nonorphans over thirteen months together with Davido, we partnered with the Smithsonian Conservation Biology Institute (Dr. Janine Brown and Nicole Boisseau) and other colleagues at Save the Elephants (Davido and Dr. Iain Douglas-Hamilton) and Colorado State University (George and Dr. N. Thompson Hobbs) to compare the metabolized stress hormones of surviving orphans with those of non-orphans. These orphans’ mothers had died >2 years ago, therefore we were investigating potential long-term impacts of being orphaned on the stress response. We hypothesized we would find evidence of sustained higher stress hormone secretion in orphans because we knew firsthand just how important the mother-calf bond is in elephant society.

What we found encouraged us. Orphans did not show higher concentrations of stress hormones than non-orphans in the long-term, and it seems that increasing interactions with age mates may help to regulate their stress response. Individuals with more elephants of similar age in their family group had lower average concentrations of stress hormones. For elephants, the presence of peers may assist in recovering from the loss of one’s mother.

Orphans who live with an unrelated family group may not fare as well. Such “non-natal” orphans are the individuals that Shifra found receive the most aggression in the form of, for example, being chased short distances off to the periphery of the group. Our sample size of non-natal orphans was small because poaching in Samburu never reached the severe levels it has in other populations, therefore most families remained intact and the majority of orphans could stay with their natal group. However, the five non-natal orphans we sampled had lower average stress hormone concentrations than other individuals. We discovered from literature that long-term social stressors can result in a downregulated stress response, and that sustained low levels of cortisol are a symptom of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) in humans. More research with a larger sample size of non-natal elephant orphans is needed, but our findings from a small sample size do agree with findings in humans: a study of human orphans showed only those who felt a lack of social support developed symptoms of PTSD like low cortisol levels.

Our findings are hopeful for surviving orphans who still have other family members, and especially a healthy network of same-aged friends. Preserving bonds within social wildlife populations may be one key to making them more resilient.

Follow the Topic

-

Communications Biology

An open access journal from Nature Portfolio publishing high-quality research, reviews and commentary in all areas of the biological sciences, representing significant advances and bringing new biological insight to a specialized area of research.

Related Collections

With Collections, you can get published faster and increase your visibility.

Signalling Pathways of Innate Immunity

Publishing Model: Hybrid

Deadline: Feb 28, 2026

Forces in Cell Biology

Publishing Model: Open Access

Deadline: Apr 30, 2026

Please sign in or register for FREE

If you are a registered user on Research Communities by Springer Nature, please sign in