Southern Ocean Warming: Storms and the Importance of Robotic Observations

Published in Earth & Environment, Electrical & Electronic Engineering, and Materials

Southern Ocean heat engine: storms, currents, and unanswered questions

The Southern Ocean is a vast expanse of water encircling the Antarctic continent, pushed along by violent mid-latitude storms. It is home to the planet‑spanning Antarctic Circumpolar Current that helps regulate Earth’s climate by moving heat, carbon, and nutrients around the globe. Importantly, it provides a critical climate service by taking in over three quarters of the excess atmospheric heat caused by rising greenhouse gas emissions.

However, many questions remain. What controls the rate at which heat is transferred from the atmosphere into the ocean, and how is that heat redistributed to depth after it reaches the surface? Can we rely on satellite sea surface temperature (SST) alone to quantify ocean heat uptake? What is the influence of high-frequency, energetic processes such as storms and ocean eddies on the rate and intensity of warming? These unanswered questions leave gaping holes in our understanding of the climate system.

How Robotics Fill the Gap

To tackle these questions and capture the energetic, rapidly evolving motions we care about, we have to move beyond traditional observing systems and turn to measurements that resolve the ocean at high spatial and temporal resolutions, continuously across the seasons.

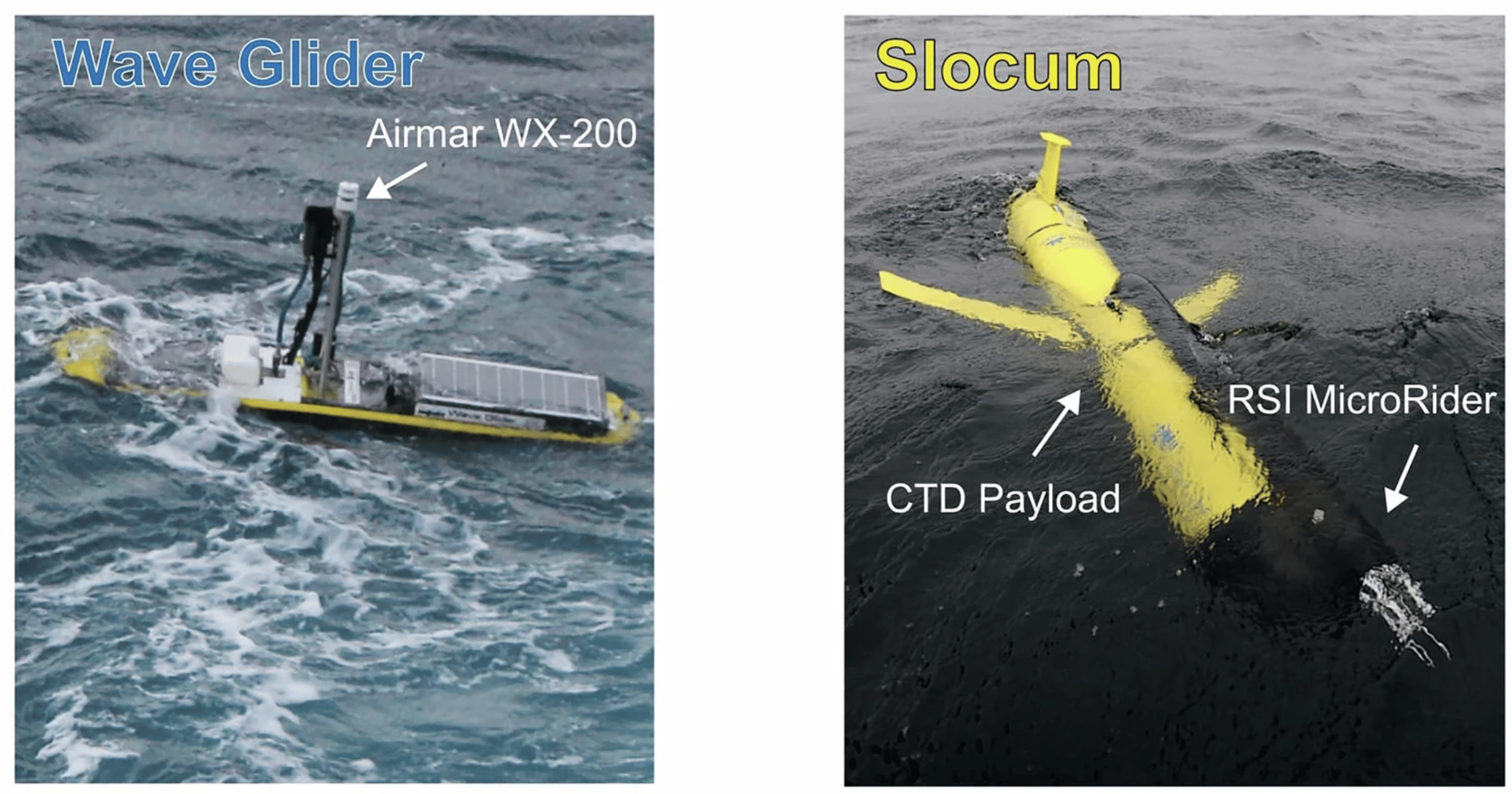

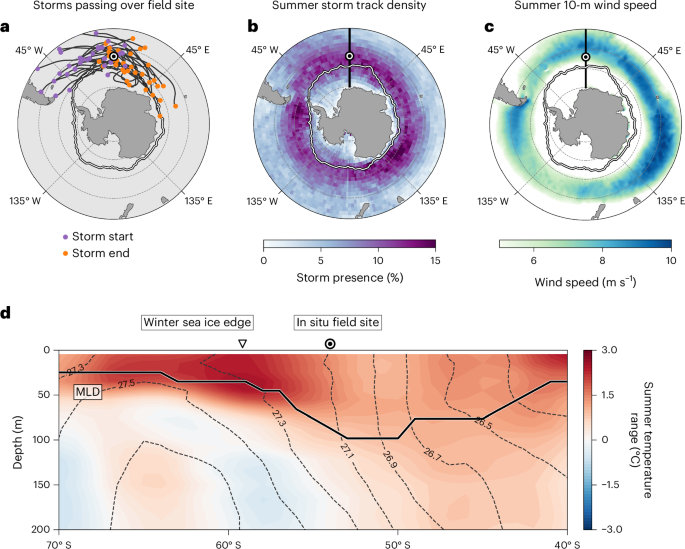

Autonomous ocean robots now make this possible, and our study puts them to work. In the polar Southern Ocean, we deployed two complementary platforms as part of the Southern Ocean Carbon-Climate Observatory’s SOSCEx-Storm campaign: a surface Wave Glider and a subsurface Slocum glider.

- The Wave Glider is an autonomous surface vehicle that uses wave energy for propulsion and is equipped with sensors measuring atmospheric conditions like wind speed.

- The Slocum glider is an underwater autonomous vehicle that profiles vertically (yo-yo’s) through the water column, measuring temperature, salinity, and turbulence. It periodically surfaces to transmit data in near-real time.

By operating together in a coordinated way over several summer months, these robots provided high-resolution, continuous observations of air-sea interactions and ocean mixing processes during storm events. The Wave Glider captures conditions above the waves, while the Slocum glider monitors the turbulent mixing beneath the surface, offering detailed insight into how storms influence heat distribution in the Southern Ocean.

Key Findings on Ocean Warming

Our robotic observations showed that the heat content of the ocean’s mixed layer—the layer of water in direct contact with the atmosphere—is not always aligned with satellite-measured SST. This “decoupling” happens because storms change the depth of the mixed layer and redistribute heat vertically, causing SST to cool even when the total heat entering the ocean remains constant.

Additionally, when storm-driven mixing deepens the mixed layer, it increasing its heat capacity and moderates surface warming, meaning that calm wind periods allow the SST to rise faster. This dynamic interplay explains why SST alone can be misleading for understanding total heat uptake.

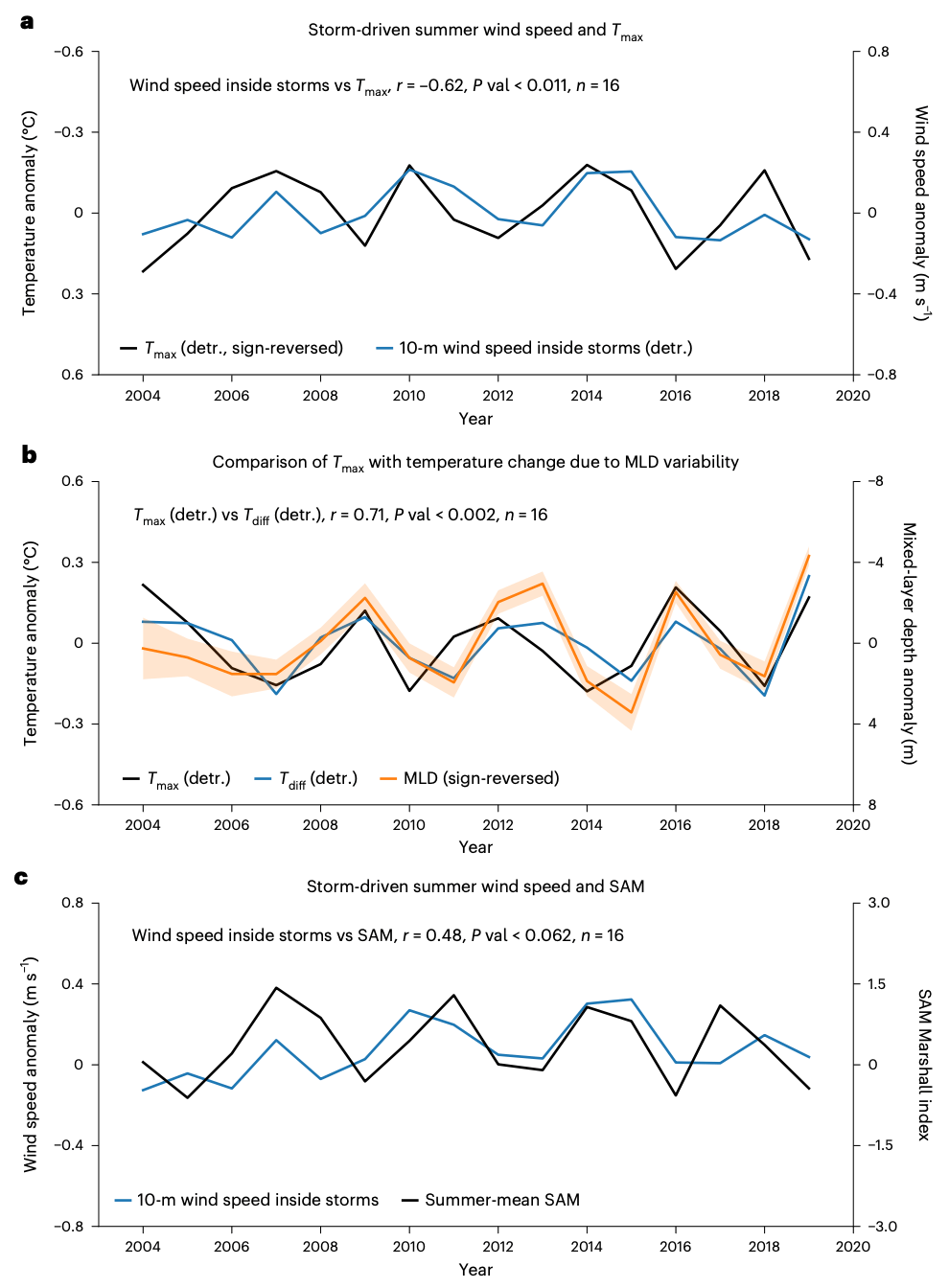

We took these results and expanded them across the Southern Ocean using a blend of reanalysis model data and satellite observations, demonstrating that the interannual variability of Southern Ocean surface temperature during summer is directly linked to the frequency and intensity of storm-driven mixing, which is regulated by the Southern Annular Mode (SAM, Fig. 3). The SAM is a key climate mode controlling the position and strength of the westerly winds that drive storms across the Southern Ocean. Years marked by stronger storm winds, commonly associated with a positive phase of the SAM, consistently show deeper mixed layers and cooler peak summer SSTs. In contrast, years with weaker storm activity lead to shallower mixed layers and warmer SSTs. This connection highlights how climate-scale variability, exerted by the SAM, operates through these storm-driven processes to set the pace of ocean warming from year to year.

Implications

Our results indicate that storm-driven changes in mixed-layer depth and entrainment provide a concrete physical pathway linking day-to-day storms to interannual variability in Southern Ocean summer SSTs and the SAM. Accurately representing storm-ocean interactions, including their impact on mixed-layer depth and shortwave radiation via cloud cover, is crucial for reducing the persistent warm summer SST biases and overly shallow mixed layers seen in many CMIP6 models. Because Southern Ocean summer SST helps set marine heatwave risk, sea-ice conditions, and the ventilation of heat and carbon to the ocean interior, improved simulation of storm effects will directly benefit future climate projections and assessments of polar climate change.

Follow the Topic

-

Nature Geoscience

A monthly multi-disciplinary journal aimed at bringing together top-quality research across the entire spectrum of the Earth Sciences along with relevant work in related areas.

Related Collections

With Collections, you can get published faster and increase your visibility.

Past sea level and ice sheet change

Publishing Model: Hybrid

Deadline: Mar 31, 2026

Urban fires around the globe

Publishing Model: Hybrid

Deadline: May 31, 2026

Please sign in or register for FREE

If you are a registered user on Research Communities by Springer Nature, please sign in