Speed dating: individual male pectoral sandpipers sample breeding sites across the Arctic

Published in Ecology & Evolution

This story starts in June 2005. We were in Barrow, the northernmost tip of Alaska, for the third summer in a row. In the previous year, we found out how we can catch male pectoral sandpipers. The species had been described as promiscuous or lekking, but nobody had studied an individually marked population. Fact is that the males are much larger and heavier than the females, and that only females invest in parental care. Females are easy to catch: you only have to put a trap on the nest, and wait until she returns to incubate her eggs. But males never come to the nest...

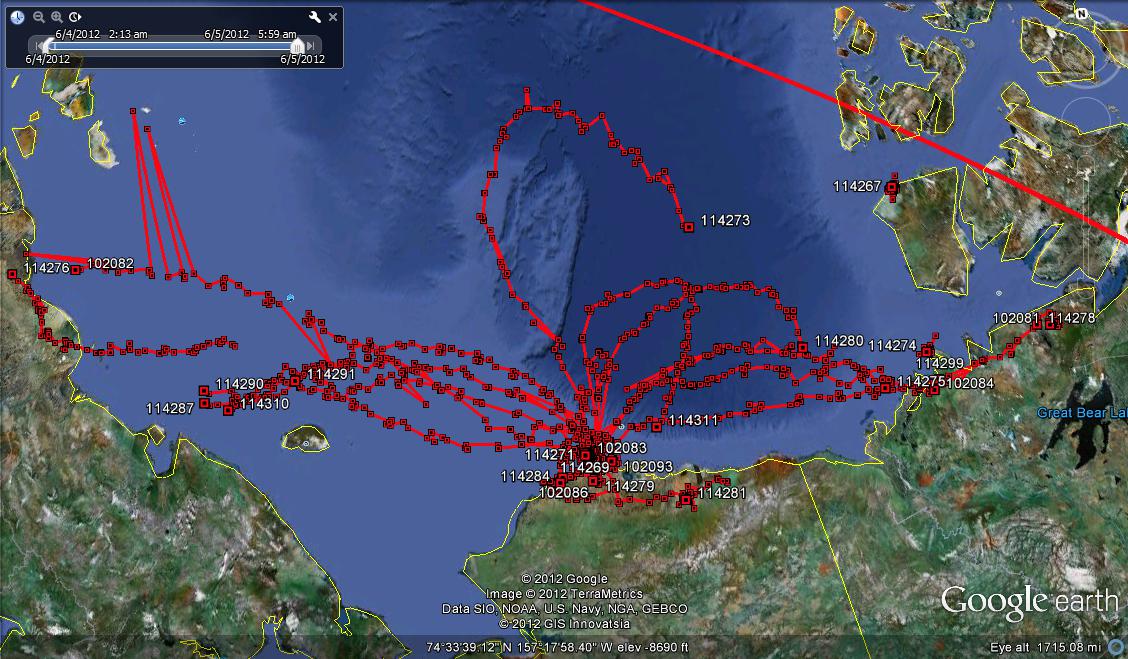

This year we came to Barrow with a large team and our goal was to catch and mark every pectoral sandpiper with a unique combination of colour bands. To follow individuals and observe and measure aspects of their behaviour, we also equipped 39 males with standard radio-transmitters. The seed of this study is laid one bright night when I was watching a radio-tagged male that was foraging together with other pectoral sandpipers in a wet part of the tundra. Suddenly, a small group flew up and started circling the area, then headed north. My radio-receiver was turned on and with the large antenna in hand I started running past the buildings until I found myself on the Beaufort Sea shore. This was the view...

I stood there and slowly turned 360 degrees with the antenna. The result was unmistakable: the pinging sound of the transmitter was loud and clear when the antenna was pointing north. Over the next 10 minutes or so, the signal became weaker until it finally disappeared. I was baffled. There was only one possible conclusion: the male was flying northwards over the pack-ice towards the pole. We did not directly observe this again, but over the next weeks it became clear that many of the males we had caught and radio-tagged left the study area, and were never seen again.

Answering where these males were going would have to wait another 7 years. During this time, we learned a lot about pectoral sandpipers on the 2 square km study site near Barrow. We learned about territory size, about competitive interactions, and about aerial and ground displays to females. We recorded the males' hooting vocalizations and in collaboration with Tobias Riede and Franz Goller, we elucidated the functional morphology of these courtship displays, showing that - just as in pigeons - males use the inflation of the esophagus to produce the characteristic sounds.

From a sample of males and females, we clipped a 1-cm piece of the innermost primary feather, and measured deuterium isotope ratios. This allowed us to determine that about 40% of the females that came to Barrow to breed were yearlings (born in the previous year), whereas all males that were present at the study site were adults (at least 2 years old). Apparently, yearling males do not even try to compete.

With the team in Barrow, we also made an effort to find all nests. Once we found a complete clutch with 4 (rarely 3) eggs, we caught the female if she had not been banded earlier, collected the eggs and placed them in an incubator. Meanwhile, the female continued incubating a set of dummy eggs we had left in her nest. This procedure was essential, because of the high risk that arctic foxes, skuas or glaucous gulls would eat our precious data. When the eggs hatched in the laboratory, we took a blood sample from the chicks and brought them back to one of the incubating females, who readily accepted their suddenly "hatched" brood.

In 2008 and 2009, we deployed another type of custom-designed, radio-telemetry based system, which involved gluing 4 g tags on the back of all caught males and females, as can be seen in the movie. The idea was to automatically record all interactions between males and females, but by "coincidence", through a side-effect of how these tags worked, we also obtained information about the level of activity of each individual. When we obtained the data, we were in for another surprise: not only were these birds arrhythmic, males also rarely seemed to rest. We returned to Barrow in 2011, this time with sleep researcher Niels Rattenborg and his then-PhD-student John Lesku, to measure sleep in the brain in free-living males. The results confirmed what we had seen on the telemetry-based actograms: one male was awake 90% of the 24-h day, and in all males sleep was highly fragmented with hundreds of sleep episodes of an average duration of 15-35 seconds. Our 2008 and 2009 data further showed that the amount of activity had clear fitness consequences: the most active territorial males interacted more often with females and with more different females and they sired more offspring. The details of this story can be read here and here.

Drawing by Ninon Ballerstaedt, Max Planck Institute for Ornithology

By then, Microwave Telemetry, a US company based in Columbia, Maryland, had developed a solar-powered, satellite transmitter weighing less than 5 g. At the end of the field season, still in Barrow, we were discussing whether to try out these tags on a few males in the next season. My friend Peter Mombaerts, a neurogeneticist based in Frankfurt, was visiting us and he joined the discussion, commenting that we should think big. He argued that if we would use a small number of transmitters to "try things out" and the results turned out interesting, we would be disappointed not having done a bigger study to begin with. On the other hand, if we used a big sample right away, we would have to invest a considerable sum of money and in the worst case the results would turn out to be "not-all-that-interesting". However, we would still get a clear answer, with results that can be published, and we would be able to firmly conclude that further work in this direction was not meaningful. Heeding Peter's advice turned out to be the best decision we ever made.

In 2012, we equipped 60 males with the 5 g PTT tags. Every day, we could check - almost live - the whereabouts of our birds and what we saw certainly surpassed our suspicion. Twenty years earlier, when I was a PhD student myself, I spent a few months as a field assistant with fellow shorebird aficionado Richard (Rick) Lanctot, working on buff-breasted sandpipers, a lekking relative of the pectoral sandpiper. One long day Rick and I banded all males on a small lek near Prudhoe Bay, Alaska, and returned home exhausted but happy, because we imagined we could return the next day to finally do behavioural observations on marked individuals. However, imagine our disappointment when we returned. None of the marked males was still there... Or perhaps one was left, but the point is that these birds showed a similar behaviour to that of pectoral sandpipers, being present at the study site for only a short time. Not much later, Rick got news that one of his marked birds had been seen by an observer a few hundred kilometers away from where we had caught it. With those memories in mind, I imagined that we would "see" our satellite-tagged males moving across the tundra of the Alaskan North Slope. In fact, of the 50 birds that left Barrow, only 7 moved within Alaska. All other birds flew thousands of kilometers visiting suitable breeding habitat in the Canadian or Russian Arctic.

After the 2012 season, we considered what to do next. We could have published the results then and there, but we felt that it would be more prudent and interesting to repeat the study in another year. We considered two issues, a biological and a practical one. The latter had to do with the attachment of the satellite transmitters. In 2012, we had simply glued the tag on the lower back of the bird, but "tag-life" was often short, and we suspected that the tags simply fell off. Mihai Valcu, my resourceful partner-in-crime, developed a somewhat different method. First, he firmly glued the tag on a piece of prepared goat skin that was about double as wide as the tag. Then, the piece of goat skin was draped over and glued on the back of the bird. Indeed, with this procedure tag-life became significantly longer and we obtained more data on birds leaving the breeding habitat on their migratory journey south. The biological reason for repeating the study was that we already knew from our earlier work that breeding conditions and bird numbers in Barrow vary considerably between years. So, we reasoned that 2012 could have been an exceptional year and our data thus not representative of the species' typical movement pattern. However, this concern turned out to be unwarranted. When we repeated the study with another 60 males in 2014, the overall results were very similar. Nevertheless, we learned a thing or two from this new season. Firstly, as can be seen in the Supplementary Movie that comes with our paper, we noticed that after an extreme cold spell in Barrow in late May - early June where the tundra became completely covered with snow and ice, all males left Barrow on a relatively short trip (a few 100 km) in a south-westerly direction. A few days later, they flew back in a north-easterly direction, but only one individual returned to Barrow. This suggests that most males do not seem to target a particular breeding site where they want to go to display. Secondly, in 2012 most of the males that left Alaska flew west into the Russian Arctic, whereas in 2014 most of them flew east and visited breeding sites in the Canadian Arctic. This could just have been coincidence, or it might be related to wind patterns. The latter would suggest that male pectoral sandpipers do not have a clear goal, but are minimizing flying costs and opportunistically selecting potential breeding sites.

Acknowledgements

The study of the pectoral sandpipers near Barrow has been an amazing journey. This journey has only been possible thanks to the dedicated help of many people. Everyone that came with us to Barrow has contributed substantially, each bringing their own set of skills that were essential for the success of the project (daily measuring territory size of all individuals throughout the season, cooking a tasteful hot meal after a long day, caring for eggs and freshly hatched chicks in the lab, or serving coffee and whiskey in the field during the coldest hours of the very early morning while rope-dragging to find nests: it all counts!). Apart from my co-author Mihai Valcu, there are three people I want to mention by name. Without them, the pectoral sandpiper project would not have existed. The first one is Richard Lanctot, shorebird coordinator at the US Fish and Wildlife Service in Anchorage. In the early 90s, he introduced me to work with Alaskan shorebirds, including pectoral sandpipers, and in 2003 he invited me to come to Barrow. I am immensely grateful and greatly indebted to a wonderful friend, superb ornithologist and behavioural ecologist, and dedicated shorebird researcher. The second person is Silke Steiger, who was my PhD student at the time. She taught me to never, never ever, give up. In 2004, we caught the first male pectoral sandpipers together. We did not know what we were doing, we did not understand these birds, and we did not realize that it was a low-density year. We chased individual males non-stop for up to 7 hours, but most of them did end up in our net. No, all of them. The third one is Wolfgang Forstmeier, a behavioural ecologist and member of my lab in Seewiesen. Wolfgang and Mihai taught me the importance of intense competition to increase success. No, we are not like pectoral sandpipers, and success was not measured in the number of interactions with females. However, under the midnight sun, we did compete for which team caught most birds, and for who found most nests. And with that, it became a perfect mix of hard work and great fun.

Photo: Katharina Kapetanopoulos, June 2012, Max Planck Institute for Ornithology

Other photos in this post: Bart Kempenaers

Please sign in or register for FREE

If you are a registered user on Research Communities by Springer Nature, please sign in