Structure-based network analysis predicts pathogenic variants in human proteins associated with inherited retinal disease

Published in Cell & Molecular Biology, Genetics & Genomics, and General & Internal Medicine

Background

As genetic sequencing has become increasingly available and less costly, a growing number of patients with clinical presentations of suspected genetic origin are undergoing targeted or whole exome sequencing. Despite improved accessibility, the genetic basis of disease for a considerable proportion of these patients remains unclear following sequencing1. Inherited retinal diseases (IRD), whereby rod and cone photoreceptors degenerate, are a group of Mendelian disorders that represent an important cause of vision loss2. With the advancement in availability of genetic testing3-6 and the lower cost of exome sequencing, IRD is a field with increasing promise and possibility for gene therapy interventions. However, among patients with an IRD, approximately 30% do not have a clear genetic basis despite classic retinal changes and decrease in visual and retinal function7, making them ineligible candidates for treatment. For these patients, additional tools are needed to better define genetic variants that are not among the group of known causal variants (i.e. variants of uncertain significance -- VUS).

Contribution

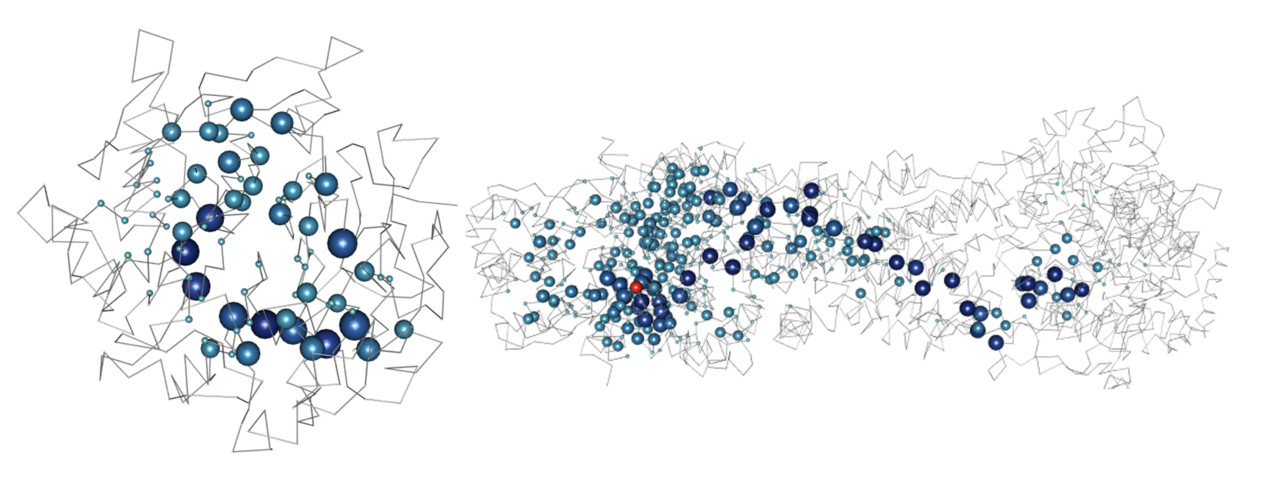

We developed structure-based network analysis (SBNA) which leverages the application of network theory to protein structure data with the goal of quantifying local residue connectivity, bridging interactions, and ligand proximity in order to identify amino acid residues that are topologically important8,9. Using x-ray crystallography and cryogenic electron microscopy (cryo-EM) data, it models proteins as networks of connected amino acids to quantitatively estimate the topological importance of each amino acid as it relates to others in the protein, protein complex or protein-ligand interaction. This approach is distinct from prior computational tools that use structural information because it is not reliant on pre-defined secondary structure elements; rather, it analyzes the crystallized tertiary structure of the folded protein as a network of weighted inter-residue interactions. Additionally, this approach does not require training on pre-labeled phenotypic data which means that it can provide a metric that is specifically focused on first-principle structural information. Approaches that require training on phenotypic data are limited by sparsely available annotations10, and previous studies suggest that some of these algorithms may also have considerable false discovery rates11,12. Furthermore, many of these algorithms are limited by circularity, with duplication of variants in the training and test datasets as well as variants from the same protein within the training and test datasets13. The clinical applicability of these approaches has been limited as a result13,14.

Results

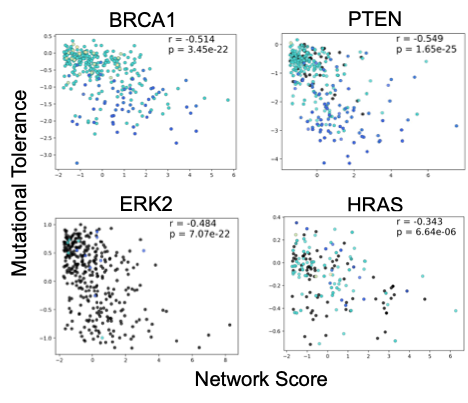

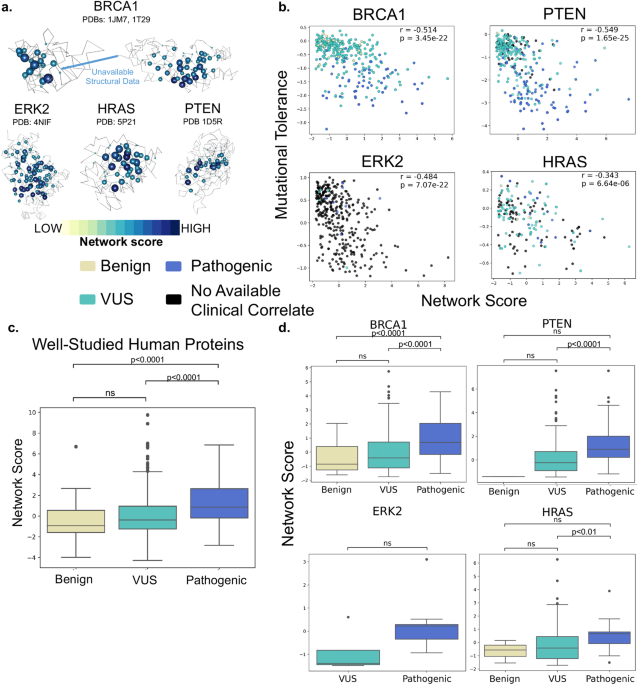

SBNA has previously been successfully utilized to identify variant-constrained amino acid residues in viral proteins8,15. As humans present a far greater level of genetic complexity, we first tested SBNA in 4 well-studied human disease-associated proteins (BRCA1, HRAS, PTEN, and ERK2) with available high-quality structural data. In addition, these proteins had published in vitro saturation mutagenesis experiments, which allowed us to extract the functional consequence of all missense variants and quantify mutational tolerance16-19. We found that SBNA scores correlate strongly with deep mutagenesis data (Figure 1).

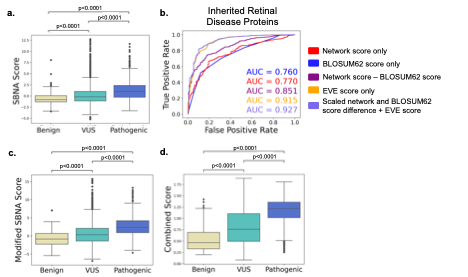

Encouraged by these results, we then applied SBNA to a dataset of 47 IRD-associated genes with available high-quality crystal structure data. Within this dataset, SBNA scores reliably identified disease-causing variants according to phenotype definitions from the ClinVar database10 (Figure 2A). To move from aggregate statistics to prediction of pathogenicity using network scores, we constructed a modified score that incorporates not only the SBNA network score but also the degree of chemical and side chain dissimilarity between the reference and mutant amino acid at that position (since missense variants vary in this regard). To capture the latter effect, we subtracted the BLOSUM62 matrix score from the SBNA score (which we will now refer to as the modified SBNA score) to allow for a distinction between non-conservative substitutions (e.g. ILE →TRP) and conservative ones (e.g. ILE → LEU) 20. Modified SBNA scores predicted variant pathogenicity (AUC 0.851; Figure 2B, C) and outperformed network scores alone, BLOSUM62 scores alone and relevant solvent accessibility (RSA) scores alone. Importantly, these models do not require any training on phenotypic data. Model performance was further augmented by incorporating orthogonal data from EVE scores (AUC = 0.927; Figure 2B, D), which are based on evolutionary multiple sequence alignments.

Figure 2. Structure-based network analysis identifies pathogenic variants in inherited retinal disease proteins. (A) Pooled comparison between network scores for variants with available clinical phenotype data for all 47 inherited retinal disease proteins. (B) ROC curves for network scores alone (red), BLOSUM62 scores alone (blue), the difference between network scores and BLOSUM62 scores (purple), EVE scores (orange) and the sum of EVE scores and the scaled difference between network scores and BLOSUM62 scores (light purple). ROC curves were determined using allvariants with available clinical phenotype data for all 47 inherited retinal disease proteins. AUC values are show for each curve. (C) Pooled comparison between the difference between network scores and BLOSUM62 scores for variants with available clinical phenotype data for all 47 inherited retinal disease proteins. (D) Pooled comparison between the sum of EVE scores and the scaled difference between network scores and BLOSUM62 scores (“combined score”) for variants with available clinical phenotype data for all 47 inherited retinal disease proteins.

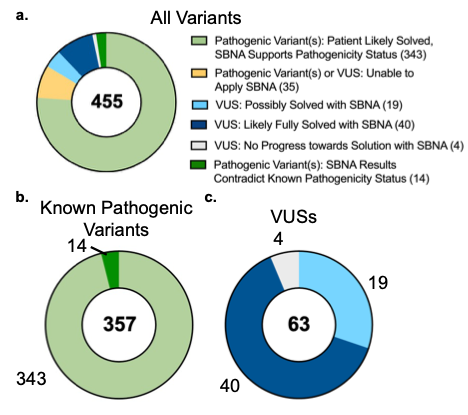

Finally, we applied this approach to 455 patients at Massachusetts Eye and Ear carrying variants of interest in the 47 IRD genes (Figure 3A). Before applying SBNA, 357 patients were found to have variants that were “likely causal” while 63 patients harbored one or more VUSs that prohibited a molecular diagnosis. The remaining 35 patients had non-missense variants or variants within a region that lacks available structural data and were therefore excluded. For the 357 patients who harbored known pathogenic variants sufficient to cause disease, the modified SBNA scores were concordant with these pathogenicity categorizations in 96.0% of cases (Figure 3B). For the 63 patients with VUSs as categorized by ACMG/AMP standards21 and/or ClinVar, the modified SBNA scores offered support for a genetic cause of disease for 40 patients (23 unique variants, Figure 3C).

Figure 3. SBNA helps identify pathogenic variants in patients with inherited retinal disease. (A) Categorization of results from application of modified structure-based network analysis (SBNA) to a dataset of possibly solving patient variants. Results were further subdivided into those from patients with known putative genetic causes of disease (B) and those from patients with only VUSs in known inherited retinal disease-associated genes (C).

Despite evidence of strong performance when applied to IRD-associated proteins, SBNA remains broadly limited by the availability of high-quality structural data for proteins of interest. This structural coverage must also overlap with the availability of high-quality phenotypic data from ClinVar, limiting the scope of analysis. Applying AlphaFold2 may provide a path towards overcoming this limitation. To further establish that AlphaFold2 can help to overcome the limited availability of high-quality structural data for SBNA, we selected 10 IRD-associated genes without available structural data that had a considerable amount of data in ClinVar. We performed SBNA on the AlphaFold2-generated structures for these genes and found a significant difference between the SBNA scores assigned to benign and pathogenic variants (Figure 4). These results suggest that AlphaFold2 could potentially be useful in expanding the applicability of SBNA, although it is not clear that the quality of this analysis would be superior to that performed on experimentally generated structural data.

Figure 4. AlphaFold2 improves coverage for SBNA. Ten IRD-associated genes without available structural data were selected, and SBNA scores were calculated for the full AlphaFold2 structures.

Conclusion

In conclusion, our results suggest that SBNA provides meaningful insights for patients with an unclear genetic basis for their clinical symptoms, particularly for patients with inherited retinal diseases. Importantly, we note that this method is based purely on structural principles rather than training on labeled outcome data, which means that it provides both an unbiased prediction of pathogenicity and the mechanism of pathogenicity (i.e. structural change) is proposed.

References

- Cooper, G. M. & Shendure, J. Needles in stacks of needles: finding disease-causal variants in a wealth of genomic data. Nat Rev Genet 12, 628-640, doi:10.1038/nrg3046 (2011).

- Berger, W., Kloeckener-Gruissem, B. & Neidhardt, J. The molecular basis of human retinal and vitreoretinal diseases. Prog Retin Eye Res 29, 335-375, doi:10.1016/j.preteyeres.2010.03.004 (2010).

- Consugar, M. B. et al. Panel-based genetic diagnostic testing for inherited eye diseases is highly accurate and reproducible, and more sensitive for variant detection, than exome sequencing. Genet Med 17, 253-261, doi:10.1038/gim.2014.172 (2015).

- Wang, F. et al. Next generation sequencing-based molecular diagnosis of retinitis pigmentosa: identification of a novel genotype-phenotype correlation and clinical refinements. Hum Genet 133, 331-345, doi:10.1007/s00439-013-1381-5 (2014).

- Ge, Z. et al. NGS-based Molecular diagnosis of 105 eyeGENE((R)) probands with Retinitis Pigmentosa. Sci Rep5, 18287, doi:10.1038/srep18287 (2015).

- Hafler, B. P. Clinical Progress in Inherited Retinal Degenerations: Gene Therapy Clinical Trials and Advances in Genetic Sequencing. Retina 37, 417-423, doi:10.1097/IAE.0000000000001341 (2017).

- Ben-Yosef, T. Inherited Retinal Diseases. Int J Mol Sci 23, doi:10.3390/ijms232113467 (2022).

- Gaiha, G. D. et al. Structural topology defines protective CD8(+) T cell epitopes in the HIV proteome. Science364, 480-484, doi:10.1126/science.aav5095 (2019).

- Berman, H. M. et al. The Protein Data Bank. Nucleic Acids Res 28, 235-242, doi:10.1093/nar/28.1.235 (2000).

- Landrum, M. J. et al. ClinVar: improvements to accessing data. Nucleic Acids Res 48, D835-D844, doi:10.1093/nar/gkz972 (2020).

- Wang, T. et al. Probability of phenotypically detectable protein damage by ENU-induced mutations in the Mutagenetix database. Nat Commun 9, 441, doi:10.1038/s41467-017-02806-4 (2018).

- Miosge, L. A. et al. Comparison of predicted and actual consequences of missense mutations. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 112, E5189-5198, doi:10.1073/pnas.1511585112 (2015).

- Grimm, D. G. et al. The evaluation of tools used to predict the impact of missense variants is hindered by two types of circularity. Hum Mutat 36, 513-523, doi:10.1002/humu.22768 (2015).

- Richards, S. et al. Standards and guidelines for the interpretation of sequence variants: a joint consensus recommendation of the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics and the Association for Molecular Pathology. Genet Med 17, 405-424, doi:10.1038/gim.2015.30 (2015).

- Nathan, A. et al. Structure-guided T cell vaccine design for SARS-CoV-2 variants and sarbecoviruses. Cell 184, 4401-4413 e4410, doi:10.1016/j.cell.2021.06.029 (2021).

- Findlay, G. M. et al. Accurate classification of BRCA1 variants with saturation genome editing. Nature 562, 217-222, doi:10.1038/s41586-018-0461-z (2018).

- Mighell, T. L., Evans-Dutson, S. & O'Roak, B. J. A Saturation Mutagenesis Approach to Understanding PTEN Lipid Phosphatase Activity and Genotype-Phenotype Relationships. Am J Hum Genet 102, 943-955, doi:10.1016/j.ajhg.2018.03.018 (2018).

- Hidalgo, F. et al. A saturation-mutagenesis analysis of the interplay between stability and activation in Ras. Elife11, doi:10.7554/eLife.76595 (2022).

- Brenan, L. et al. Phenotypic Characterization of a Comprehensive Set of MAPK1/ERK2 Missense Mutants. Cell Rep 17, 1171-1183, doi:10.1016/j.celrep.2016.09.061 (2016).

- Eddy, S. R. Where did the BLOSUM62 alignment score matrix come from? Nat Biotechnol 22, 1035-1036, doi:10.1038/nbt0804-1035 (2004).

- Kleinberger, J., Maloney, K. A., Pollin, T. I. & Jeng, L. J. An openly available online tool for implementing the ACMG/AMP standards and guidelines for the interpretation of sequence variants. Genet Med 18, 1165, doi:10.1038/gim.2016.13 (2016).

Follow the Topic

-

npj Genomic Medicine

This is an international, peer-reviewed journal dedicated to publishing the most important scientific advances in all aspects of genomics and its application in the practice of medicine.

Related Collections

With Collections, you can get published faster and increase your visibility.

Artificial Intelligence in Genomic Medicine

Publishing Model: Open Access

Deadline: Jun 23, 2026

Genomics in precision medicine

Publishing Model: Open Access

Deadline: Apr 14, 2026

Please sign in or register for FREE

If you are a registered user on Research Communities by Springer Nature, please sign in