Teaching Large Language Models to Think Like Clinicians

Published in Bioengineering & Biotechnology and Mathematical & Computational Engineering Applications

In September 2024, our laboratory felt unusually quiet.

Many of my lab mates had just returned from the ACL conference in Thailand. Like many early-career researchers, I was eager to hear what the next big thing was. Over coffee and informal discussions, I asked a simple question:

“What is everyone focusing on right now?”

The answer was almost unanimous: reasoning in large language models.

They talked about chain-of-thought prompting, mathematical reasoning benchmarks, and datasets such as GSM-8K. I remember feeling both inspired and uneasy. Inspired—because the idea of making models reason rather than merely generate text is deeply compelling. Uneasy—because most of these advances seemed far removed from real-world, high-stakes domains.

A personal crossroads between medicine and language models

My academic journey has always sat at the intersection of disciplines. During my master’s degree at Central South University in China, my focus was firmly on medical imaging and deep learning. I spent years working with radiological data, learning firsthand how sensitive medical decision-making is—and how costly errors can be.

Figure 1: An outside view from the lab during the day (left) and the same lab late at night during ongoing research work (right) at central south university.

Later, when I began my PhD at Shanghai Jiao Tong University, I entered a lab whose primary focus was natural language processing and large language models. Suddenly, my daily work revolved around language, reasoning, and generative models rather than pixels and scans.

At that point, a question became unavoidable:

If large language models are learning to reason, why are we mostly testing that reasoning on math puzzles—rather than on human health?

Medicine is not a clean, closed-form problem. Patient narratives are messy. Symptoms are ambiguous. Diagnoses evolve. And most importantly, clinicians do not just give answers—they explain why.

That realization became the core motivation behind our paper.

Figure 2: Working in the AGI institute lab at Shanghai Jiao Tong University

China stands at the forefront of global innovation, blending deep cultural heritage with rapid technological advancement. Shanghai, as its most dynamic metropolis, embodies this spirit—an international hub of research, education, and industry—where tradition and modern science converge to shape the future.

The trust problem in medical AI

There is no shortage of excitement around using LLMs in healthcare. These models can read clinical notes, summarize patient histories, and even suggest diagnoses. But enthusiasm often hides a fundamental issue: trust.

Clinicians are understandably cautious. A correct diagnosis without a clear rationale is not enough. In real clinical practice, decisions are scrutinized, discussed, revised, and justified. A model that behaves like a “black box” is difficult—if not impossible—to integrate safely into this workflow.

Many existing approaches attempt to solve this by adding longer explanations or encouraging step-by-step reasoning. But we observed several limitations:

- Most methods were tested on a small number of models or datasets.

- Many relied on predefined answer options, unlike real clinical settings.

- Reasoning quality was rarely evaluated in a clinically meaningful way.

We did not want to simply make language models talk more. We wanted them to reason more like doctors.

Mimicking how doctors actually think

In hospitals, junior doctors propose an initial interpretation. Senior doctors refine it. Attending physicians synthesize everything into a final judgment. This layered reasoning is not a formality—it is a safety mechanism.

So we asked: What if a single large language model could simulate this process?

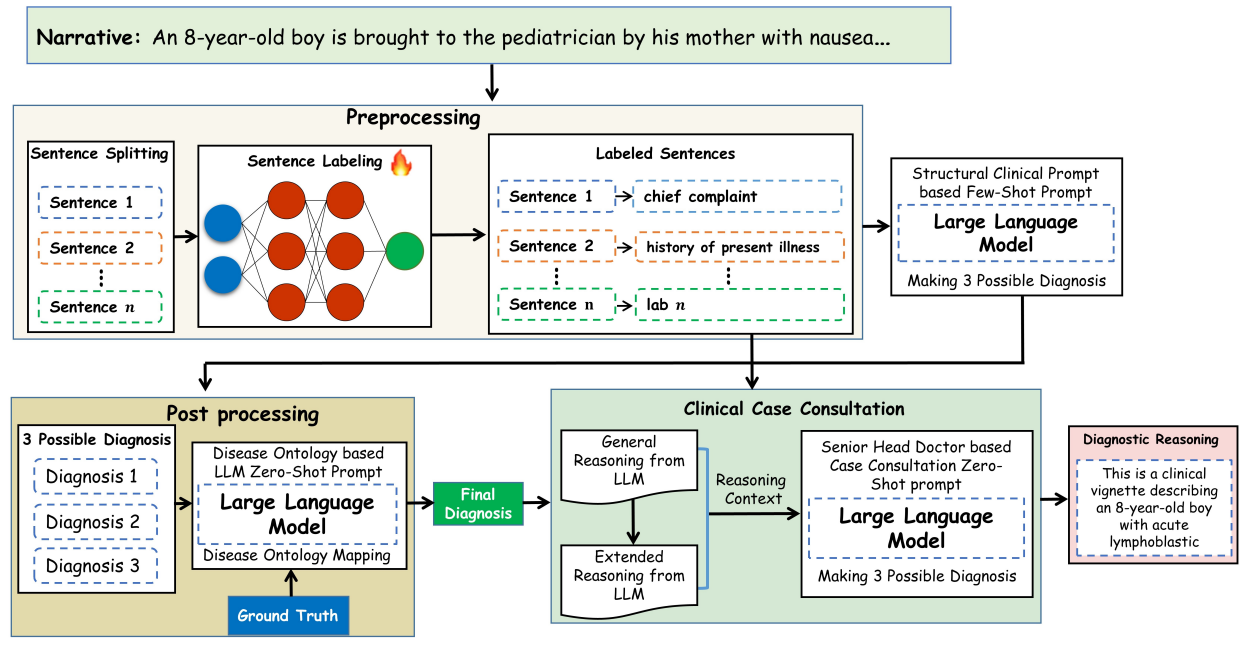

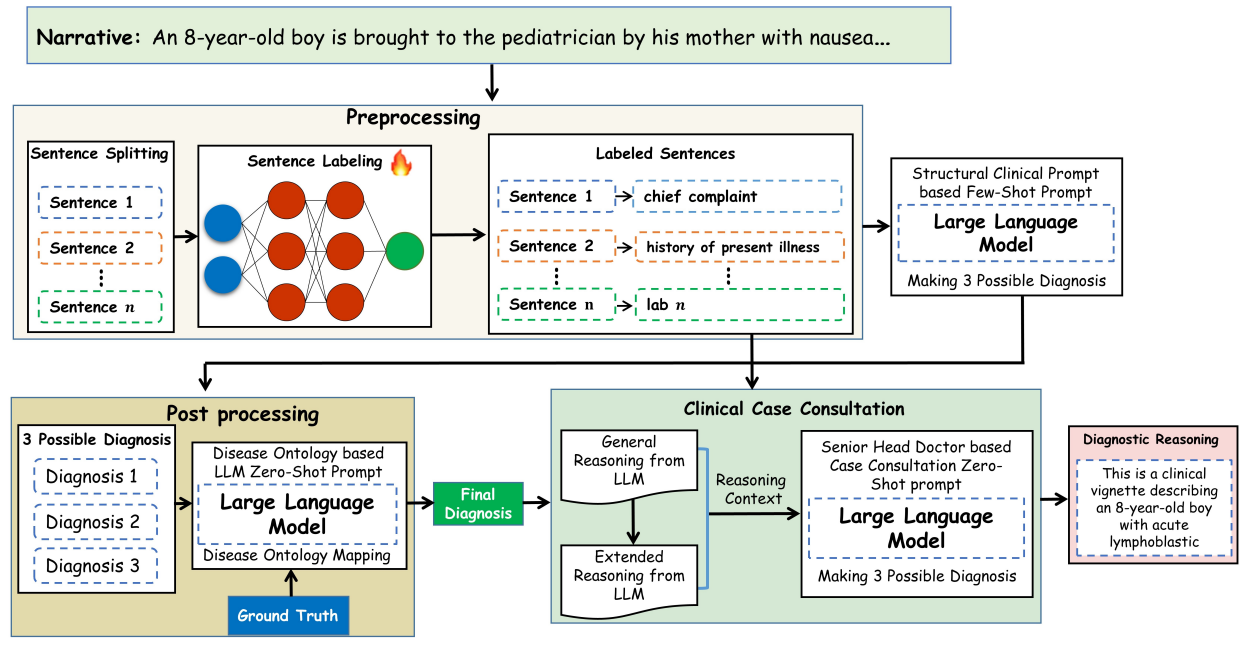

Instead of multiple separate agents, we structured the same model to reason sequentially as:

- A junior doctor generating preliminary reasoning

- A senior doctor refining that reasoning

- A head doctor synthesizing a final, coherent explanation

Before that, however, we addressed another critical issue: clinical structure.

Patient notes are unstructured narratives. Clinicians, on the other hand, think in structured components—chief complaint, history of present illness, lab findings, and so on. We therefore designed a preprocessing step that converts free-text clinical narratives into clinically meaningful segments before passing them to the language model.

Figure 3: Proposed approach for enhancing the clinical diagnosis & reasoning in LLMs

This small but crucial step dramatically improved both diagnostic accuracy and interpretability.

From black box to “white-box” reasoning

One of our central goals was transparency. Rather than treating large language models as opaque oracles, we designed a framework in which each stage of clinical reasoning is explicit, structured, and inspectable. By aligning model behavior with real clinical workflows and introducing ontology-guided validation using established medical knowledge, we ensured that diagnoses were not only linguistically plausible but clinically meaningful.

Crucially, we evaluated the framework across multiple large language models, multiple clinical reasoning datasets, and real hospital electronic health records. This breadth of evaluation mattered to us, because methods that perform well only in controlled benchmarks rarely translate into real clinical practice. The results were encouraging: across settings, we observed consistent improvements in diagnostic accuracy, reasoning quality, and clinician-rated trustworthiness. Yet, beyond the metrics, what mattered most was showing that structured reasoning can make AI systems more interpretable and clinically aligned.

Rejection, revision, and resilience

The path to publication was far from linear. We initially submitted this work to several high-profile journals, and the rejections came quickly—sometimes bluntly. Some reviewers questioned whether language models could ever be trusted in medicine; others felt the problem was too ambitious. Each rejection forced us to sharpen our claims, strengthen our evaluations, and ground our contributions more firmly in clinical reality.

When we eventually submitted to Nature Communications Medicine, the review process was demanding but constructive. Multiple rounds of revision pushed us to be more rigorous, transparent, and clinically focused. When the paper was finally accepted, it felt less like a triumph and more like confirmation that persistence—and careful refinement—matters.

For more details you may visit Authors personal webpage https://ayoub-ml.github.io/ or approach him on email (ayoubncbae@gmail.com)

Follow the Topic

-

Communications Medicine

A selective open access journal from Nature Portfolio publishing high-quality research, reviews and commentary across all clinical, translational, and public health research fields.

Related Collections

With Collections, you can get published faster and increase your visibility.

Reproductive Health

Publishing Model: Hybrid

Deadline: Mar 30, 2026

Healthy Aging

Publishing Model: Open Access

Deadline: Jun 01, 2026

Please sign in or register for FREE

If you are a registered user on Research Communities by Springer Nature, please sign in