Terrestrial magma ocean origin of the Moon

Published in Astronomy

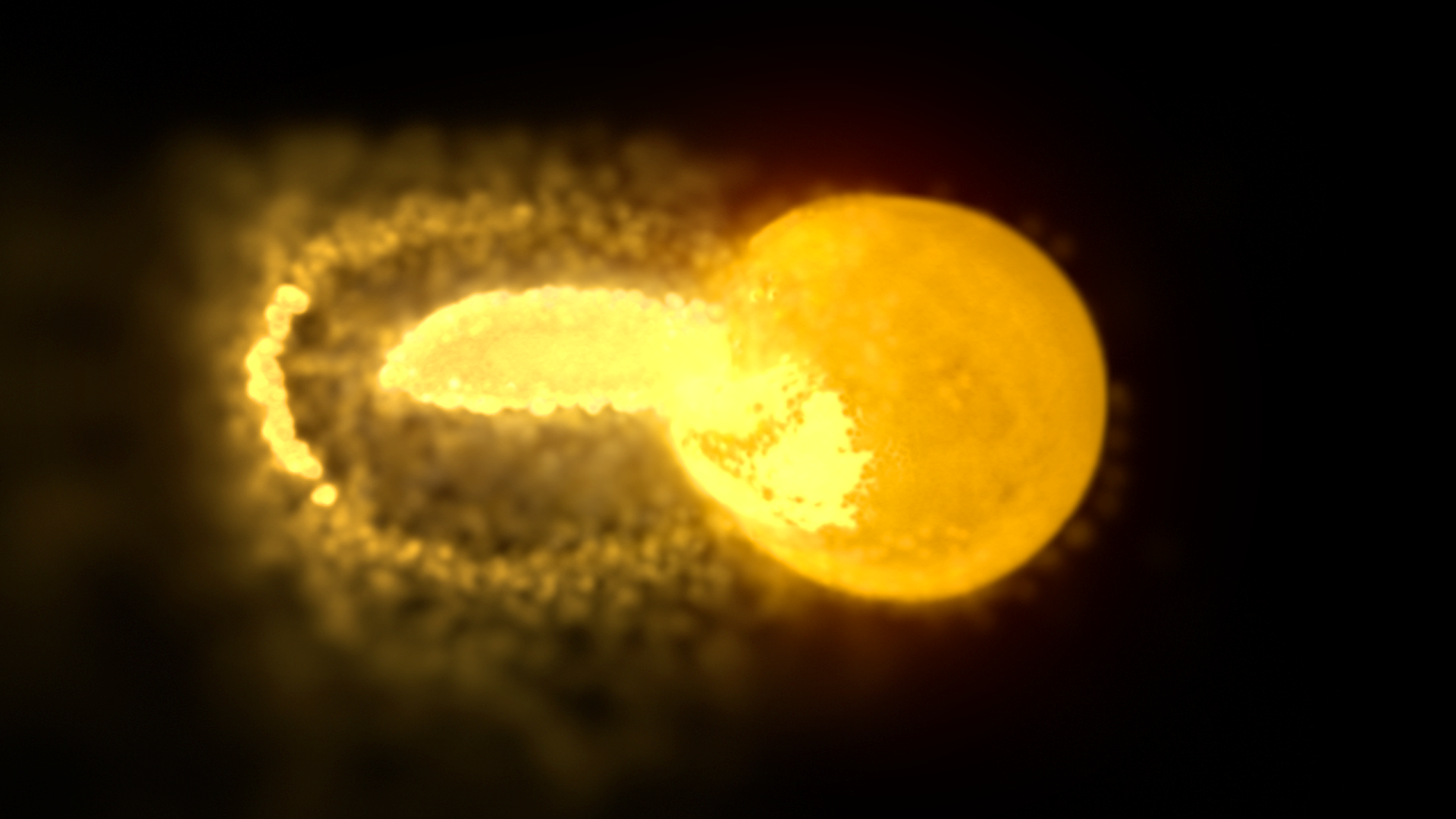

For a long time, people have speculated the origin of the Moon. To date, several models for the origin of the Moon have been suggested, e.g., fission, capture and binary formation models. Amongst these candidates, a collision between two planetary embryos, so-called "the giant impact (GI) hypothesis", has been recognised as the most favourable scenario for the formation of the Moon. According to this scenario, in the late stage of the Earth formation, a Mars-sized body collided with the proto-Earth and ejected materials to the orbit, which was later accumulated into the Moon. This hypothesis can explain almost all of the evidence of the current Earth-Moon system, e.g., a lack of iron core in the Moon, the angular momentum in the Earth-Moon system, and so force. Numerical simulations have also supported this scenario and made it a de facto standard scenario. The following figure shows one snapshot of our paper.

Simulation: Natsuki Hosono

Visualization: Hirotaka Nakayama

Four-Dimensional Digital Univers Project, National Astronomical

Observatory of Japan

Lately, however, a severe problem which makes scientists confusing was reported; the high-resolution measurements of the isotopic composition suggested that the Moon should be formed from the Earth-originated materials, while numerical simulations concluded that the Moon should come from the impactor-originated materials. This discrepancy is sometimes referred to as "isotopic crisis." To date, many researchers, including me, have tackled with this problem.

If I recall correctly, it was the summer in 2014 when I first made the acquaintance of Shun-ichiro Karato who told me that he had an idea to overcome the crisis from a geophysical point of view, namely, the magma ocean. According to his idea, due to the difference of sensitivity to shock heating between silicate melts and solid rocks, a substantial fraction of materials would be ejected from the magma ocean. He would like us to confirm his idea with numerical simulations. However, in order to test his idea with numerical simulations, we need an equation of state which is appropriate to molten silicate. Fortunately, his team has developed an appropriate model of state for molten rocks.

Let me write the struggle against the equation of state. Karato-san gave me a reference to their equation of state, and it is given in the form of pressure as a function of volume and temperature. On the other hand, numerical hydrodynamic methods require a function of density and internal energy. Conversion between density and volume is trivial; density is reciprocal of volume. However, conversion between temperature and internal energy is not. When it comes to solids, there are well-known methods, namely, Einstein/Debye models. So the first step of this research was to construct the function to convert temperature and internal energy. Hence, I have re-derived their equation of state from a partition function and finally obtained their equation of state in a density-energy form.

Numerical simulations with a new equation of state were challenging, but I finally get a preliminary result of the giant impact onto the magma ocean in Augst, 2016. In the beginning, I felt like I wondered whether the magma ocean could change the result. It was exciting; the result was largely different; there seem to be more massive materials from the Earth when we put a magma ocean on the proto-Earth. Hard times still last for about two years, but our paper has finally been accepted.

The referees gave us helpful comments. Thanks to their comments, our paper got improved. However, this paper is not the last word for the Moon formation. There are several criticisms and questions to our scenario. In both geochemical and planetary science points of view, there are future works. What will occur in the post-impact proto-Earth? How will the disc evolve and accumulate into the Moon? If you are interested in, I will recommend to give it a go!

For detail, see https://www.nature.com/articles/s41561-019-0354-2

Follow the Topic

-

Nature Geoscience

A monthly multi-disciplinary journal aimed at bringing together top-quality research across the entire spectrum of the Earth Sciences along with relevant work in related areas.

Related Collections

With Collections, you can get published faster and increase your visibility.

Fluids in seismicity

Publishing Model: Hybrid

Deadline: Mar 31, 2026

Past sea level and ice sheet change

Publishing Model: Hybrid

Deadline: Mar 31, 2026

Please sign in or register for FREE

If you are a registered user on Research Communities by Springer Nature, please sign in