The 1918 influenza pandemic in its time –will we learn for the future?

Published in Microbiology

In 1918, a new pandemic influenza virus spread through the human population. Within a year, it killed at least 35 million people and possibly 100 million. Adjusting for population growth, that is equivalent to a death toll today of from roughly 140 million to 425 million.

Over-all case mortality in the developed world was around 2%, but in the developing world, case mortality was generally higher, particularly in India, and in isolated regions with virgin populations, the death toll was truly frightening. In Samoa, for example, 16% of the population died in 14 days. Even in the West, the over-all case mortality numbers mislead, since certain sub-groups suffered much higher percentages. Most of the dead were healthy young adults age 18 to 45. From 3-8% of the entire population in that age range died. Different studies of pregnant women in the United States found case mortality rates ranging from 21% to 73%. A Metropolitan Life Insurance study of those it insured found that 3.28% of that entire population of industrial workers in the U.S. aged 20-50 died, and 6.21% of the entire population of U.S. miners in that age group died [1]; case mortality was likely 10%-30% for those groups.

St. Louis Red Cross Motor Corps on duty, Oct 2018. Source: US Library of Congress Prints and Photographs

While much attention has been focused on the young adults who died, a comparable death toll among children age 1 through 4 in the U.S. would equal the number who die of all causes over a 24 year period [personal communication; Carter Mecher, Jan. 5, 2018].

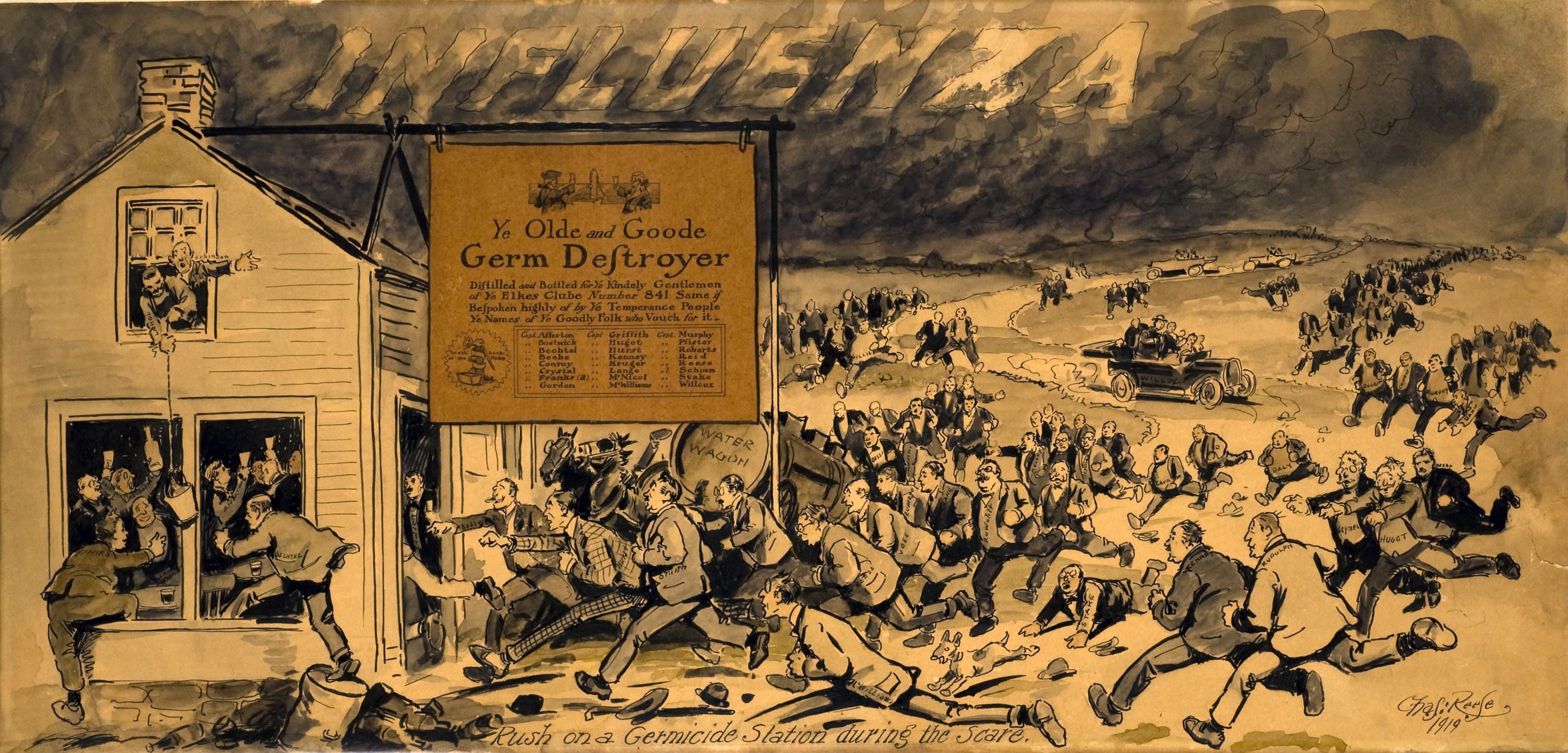

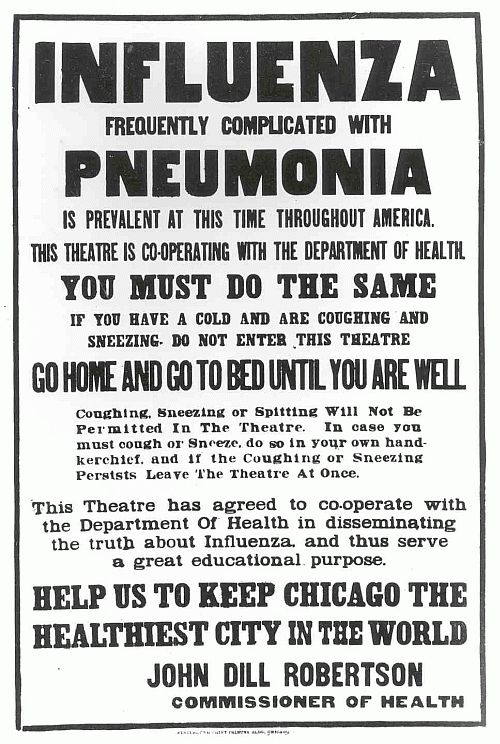

On top of that, probably two-thirds of the deaths were compressed into a period of about 12 weeks, from mid-September to mid-December 1918. And, during that peak, no one knew when or even if it would end.For good reason, the pandemic frightened people and stressed the entire society. That fear and stress was compounded, rather than alleviated, by attempts to offer false reassurance by public officials and the press. The very name of the disease emerged from falsity. It became known as “Spanish Flu” not because it began in Spain— it hit many other places before erupting there—but because Spain was not at war and its press wrote about the disease, while other countries’ censored press published nothing. And falsehoods only began with the name. Surgeon General of the United States Rupert Blue said, "There is no cause for alarm if precautions are observed [2]". The Associated Press quoted another physician involved in national health policy, "The so-called Spanish influenza is nothing more or less than old fashioned grippe". New York City’s public health director declared "other bronchial diseases and not the so-called Spanish influenza… [caused] the illness of the majority of persons who were reported to be ill with influenza [3]”. In Little Rock, Arkansas, the Arkansas Gazette ran a headline stating, "Spanish influenza is plain la grippe-- same old fever and chills [4]". Just seven miles away an Army hospital was admitting eight thousand soldiers in four days, then ceased further admissions, leaving many thousands more sick in barracks, and a doctor there recorded "miles of corridors with a double row of cots with influenza patients... There is only death and destruction [5]." The reassurances were counterproductive. People knew this was no ordinary influenza. They knew because some deaths occurred in 24 hours or less, and they knew because of some horrific symptoms, including bleeding from not only the nose and mouth but from the eyes and ears. They knew because in such cities as Philadelphia priests drove horse-drawn carts down the street calling upon people to bring out their dead. Recognizing they were being lied to, knowing they could believe nothing they were being told, trust evaporated.

Rush on a germicide station during the scare . Source: US National Library of Medicine

Ultimately, society is based on trust and human contact, and the lies destroyed both. Without them, society began to break apart. As one man who lived through it recalled, "It kept people apart... You had no school life, you had no church life, you had nothing... It completely destroyed all family and community life. People were afraid to kiss one another, people were afraid to eat with one another... It destroyed those contacts and destroyed the intimacy that existed amongst people”. In Philadelphia, one man left his emergency hospital and drove home twelve miles every night. He saw so few cars on the road he took to counting them. One night he saw not a single other car. "The life of the city had almost stopped” he said.

At the same time, on the other side of world, another man stepped outside another hospital in New Zealand, and remarked, "I stood in the middle of Wellington City at 2 P.M. on a weekday afternoon, and there was not a soul to be seen-- no trams running, no shops open, and the only traffic was a single ambulance. It was really a City of the Dead [6]".

In both big cities and rural areas, influenza sufferers starved to death not from lack of food but because neighbors, friends, even family were too afraid to bring them food. Victor Vaughan, head of the U.S. Army’s Division of Communicable Diseases and before and after the war dean of the University of Michigan medical school, watched the deterioration of society with a different kind of fear and wrote, “If the present rate of acceleration continues for a few more weeks, civilization could disappear from the face of the earth”.

Every reader of this journal understands that future influenza pandemics are inevitable, and most readers are probably generally familiar with the fact that since 2003 two different avian influenza viruses have infected more than 2300 people, with a 44% case mortality rate. So far, except in special circumstances, all these infections have come from direct contact with birds, but every infection offers an opportunity for the virus to adapt, either through reassortment or mutation, to humans in a way that allows it to pass from person to person.

Most readers also probably recognize that, for all the medical advances since 1918, we remain unacceptably vulnerable to a lethal one. We do have vaccines now, but with current technologies it would still take months to develop, manufacture, distribute, and administer a vaccine—and it would be far short of 100% effective. Since 2003, influenza vaccine effectiveness for seasonal influenza has ranged from 10% to 61%, and there is no reason to believe a pandemic vaccine would deliver better results. As far as actual medical care, modern ICUs can provide great supportive care for those suffering from acute respiratory distress syndrome—but only if those ICU beds are available. A severe pandemic would quickly fill them, greatly limiting what could be done for those who fall sick later. And while antibiotics would dramatically cut the death toll from bacterial pneumonias following influenza—the cause of most 1918 deaths-- case mortality for that today is still 7% [7]. And that is assuming an unlikely best case: that hospitals have adequate supplies. The reality is, however, that the best case will not obtain; with just-in-time inventory systems and with vast numbers of production-line workers, truck drivers, and air traffic controllers out sick, supply chains are nearly certain to break down, causing concomitant shortages of everything from antibiotics to syringes.

As the 2009 pandemic—the mildest ever known, although quite likely many other mild pandemics passed without notice through history, before modern surveillance was available to identify a new virus-- demonstrated, the world is not ready. So it is incumbent upon us to learn everything we can from the 1918 experience.

The first lesson is to take pandemic influenza far more seriously. Public health officials understand this. When outgoing U.S. Center for Disease Control and Prevention head Tom Frieden was asked what kept him up at night, he replied, “The biggest concern is always for an influenza pandemic...[It] really is the worst-case scenario [8].” Yet concerns of public health professionals have not translated into policy or budget priorities. A December 2017 U.S. national security document, for example, listed AIDS and SARS as threats but not influenza, and spending on the development of a universal influenza vaccine pales in comparison to spending on lesser threats. The ordinariness of influenza, the familiarity with it, mitigates against politicians making it a priority, even though a universal vaccine targeting conserved portions of the virus would likely be more effective than current seasonal vaccines targeting rapidly mutating antigens, a mutation rate which partly accounts for the poor vaccine performance. Such a universal vaccine would of course protect against both pandemic virus and seasonal viruses, which kill an estimated 290,000-650,000 people annually worldwide.

The second lesson is that policy makers must tell the truth, and they must tell it early, often, and in full-- including acknowledgement of any mistakes, miscalculations, shortages, etc. That is the only way to remain the primary source for information, the only way to prevent the public from abandoning them for unreliable information online. Maintaining trust is absolutely crucial for the public to comply with any guidance regarding so-called Non-Pharmaceutical Interventions. Getting and sustaining compliance will be difficult under any circumstances. In Mexico City in 2009, for example, the government recommended using masks on public transit and distributed free ones; the question of effectiveness aside, usage peaked at 65% but three days later fell under 30% [9]. A corollary to the lesson about telling the truth is that those in authority—as a general rule, political leaders who oversee public health professionals-- must accept the truth. In 2009 Brazil was among the most reticent countries in the world in giving out information, whether to international partners or internally; it also had among the worst outcomes, especially in its southern region, and a thorough analysis is needed to see if there is a causal connection [10].

These first two lessons may be impossible to learn because they require politicians to make rational judgments irrespective of what helps them politically. In 2009, Mexico did tell the truth and too many other countries punished it economically—and irrationally-- for doing so; it spent $180 million handling the outbreak, but lost $9 billion [10], setting a terrible precedent which will not encourage politicians in a future health crisis to be forthcoming. Mexico aside, in 2009 many countries also ignored their own plans and WHO recommendations and reacted irrationally and took at best useless and at worst counter-productive steps. Nor did reaction by political leaders to the more recent Ebola outbreak suggest a lesson learned. That is the biggest challenge for public health leaders: convincing political leaders who oversee them to accept their advice.

The third lesson is to approach a severe pandemic from an interdisciplinary perspective, recognizing the economic and social disruption it will inevitably create. This actually could be a path to involve top political leadership in, and thus get them to buy into, preparedness efforts.

The fourth lesson is to continue to mine the five pandemics we have data from—1889 1918, 1957, 1968, and 2009—for insights. Almost nothing has been done with 1889, and while some 1918 data has been analyzed, a treasure trove remains, some of it published contemporaneously, some of it assembled but never published. For example, data by a pioneer epidemiologist George Soper proves that quarantine would be useless except in very limited and special circumstances [11], while data from 1889, 1918, and a recrudescence in 1920 deepens if not challenges our understanding of school children’s role in spreading the disease. This data needs to be explored and analyzed.

The final lesson, again from 2009, is that planning is merely a necessary but insufficient requisite for preparation; it does not equal preparation. Planning is in fact useless, unless those plans are implemented. That is the biggest challenge to public health regarding influenza, and for that matter on many other issues: getting those above their pay grade to pay attention.

References

1. Edwin Jordan, Epidemic Influenza, 251.

2. Washington Evening Star, Oct 13, 1918.

3. JAMA, 9/21/18 p 986; Duffy, A History of Public Health in NYC 1866-1966, 289-290

4. Arkansas Gazette, Sept 20, 1918.

5. quoted in Pettit, "A Cruel Wind," 105.

6. Rice, Geoffrey, Black November: the 1918 Influenza Pandemic in New Zealand, Allen and Unwin, Wellington, 1988, 52.

7. Mark L. Metersky, Robert G. Masterton, Hartmut Lode, Thomas M. File Jr, Timothy Babinchak, Epidemiology, microbiology, and treatment considerations for bacterial pneumonia complicating influenza, International Journal of Infectious Diseases, 16, 5, e321-e331.

8. Sun, Lena, “Outgoing CDC Head Talks about His Successes and His Greatest Fear,” Washington Post, January 16, 2017

9. Condon BJ, Sinha T. Who is that masked person: The use of face masks on Mexico City public transportation during the Influenza A (H1N1) outbreak. Health Policy (2009), doi:10.1016/j.healthpol.2009.11.009

10. Ciro Ugarte, PAHO, presentation on 11/13/2017 at The Next Pandemic: Are We Prepared?, in the Smithsonian Museum, Washington, DC, https://www.smithsonianmag.com/science-nature/watch-livestream-next-pandemic-are-we-prepared-180967069/

11. "The influenza Pandemic in the Camps," undated draft report, Dr George Soper, Major, Sanitation Corps, U National Archives, Record Group 112; BOX 394

Please sign in or register for FREE

If you are a registered user on Research Communities by Springer Nature, please sign in