Storing carbon in European forests is not (always) enough for biodiversity

Published in Earth & Environment, Ecology & Evolution, and Agricultural & Food Science

Today, forests are increasingly expected to play a key role in two major environmental challenges: climate change and biodiversity loss. European forest policies, including the EU forest and biodiversity strategies for 2030, explicitly aim to deliver climate change mitigation through increased carbon storage in forests, while simultaneously promoting biodiversity conservation. These policies rely on the implicit assumption that increasing forest carbon stocks will also benefit biodiversity.

However, it is increasingly evident that this assumption should not be taken for granted. Across Europe, both forest area and carbon stocks in living trees have increased steadily over recent decades. Yet these trends have not necessarily translated into an improvement in the conservation status of forest habitats, which remains mostly unfavorable. This discrepancy raises a crucial question: are current European policies really delivering benefits for both climate change mitigation and biodiversity conservation?

A key reason why this question is difficult to answer is our perception of forest carbon. Carbon is stored in very different forest components. Living trees store carbon, but so do standing dead trees, fallen logs, decaying wood on the forest floor, and soil. These carbon pools are not ecologically equivalent. They differ in their origin, turnover rates, and, crucially, the biological communities they support. In particular, deadwood is a key habitat and resource base for a large share of forest species, especially fungi, insects, lichens, and mosses. Nevertheless, policy frameworks and forest monitoring systems tend to emphasize only carbon stored in living trees, largely because it is easier to measure and integrate into carbon accounting frameworks. Deadwood, in contrast, is often poorly quantified and scarce in managed forests. As a consequence, this carbon pool remains underrepresented in forest inventories and carbon accounting initiatives.

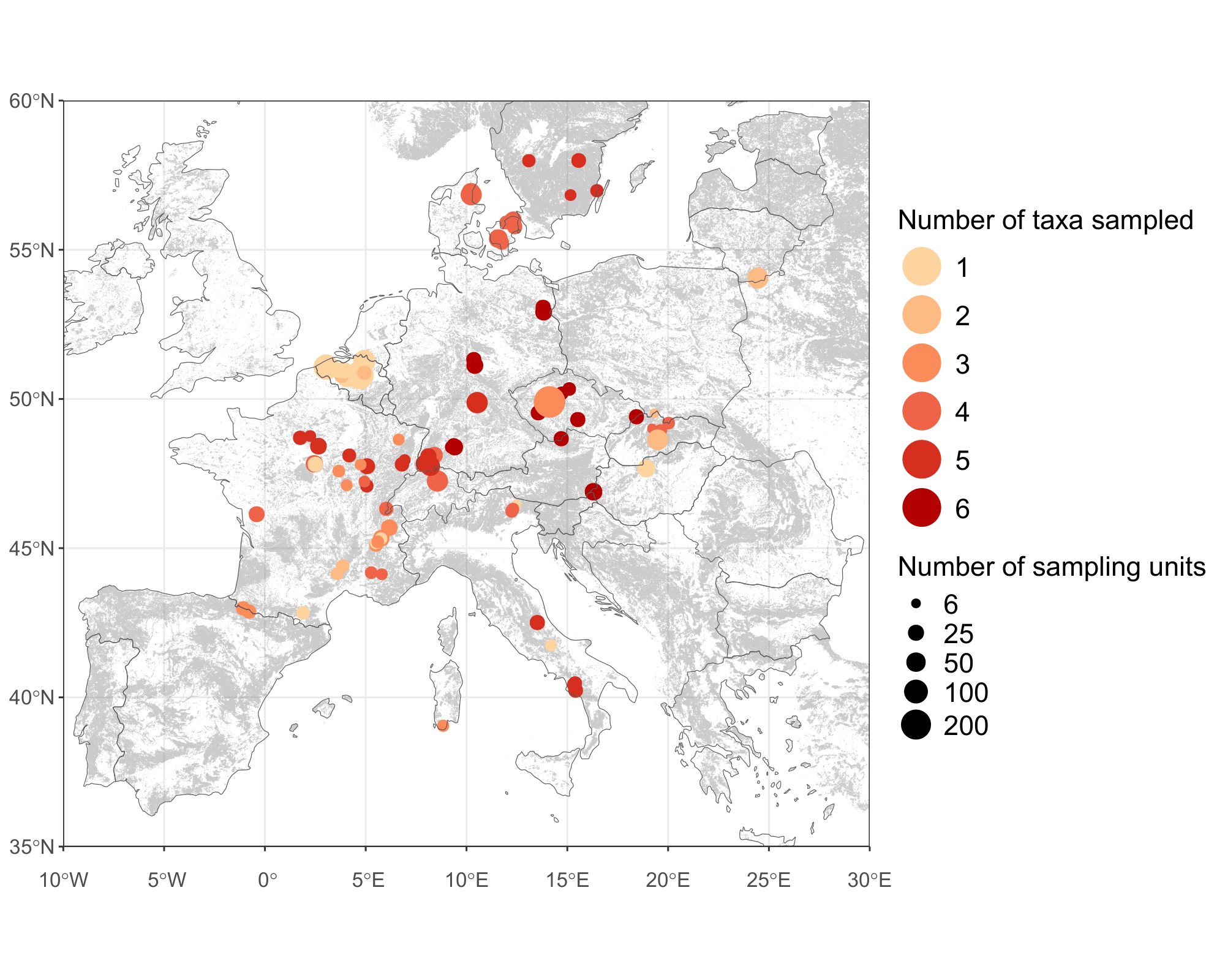

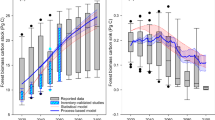

To explore how these different carbon pools are linked to biodiversity, we used the “Bottoms-Up” database (https://www.bottoms-up.eu/en/), a Europe-wide forest structure and multi-taxon dataset (Fig. 1). We combined data for vascular plants, bryophytes, lichens, fungi, saproxylic beetles, and birds with information on forest structure and carbon stocks. Working at the continental scale allowed us to move beyond local studies and ask whether general patterns emerge across European forests, despite their different management histories and environmental conditions.

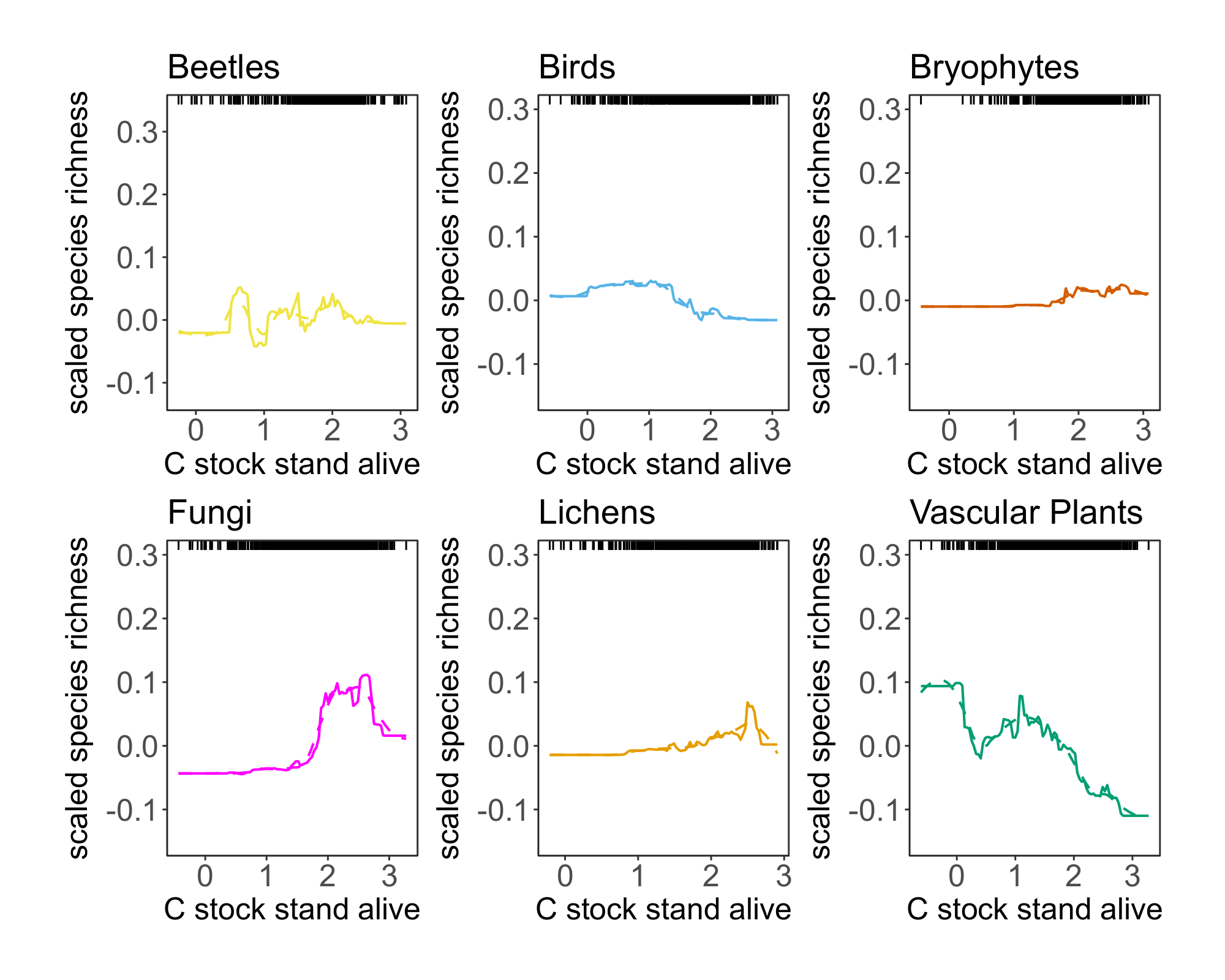

What we found challenges the idea of a universal carbon/biodiversity win-win relationship. Carbon stored in living trees showed weak or negative associations with the richness of several taxonomic groups (Fig. 2). Vascular plants, in particular, declined as living trees' carbon stocks increase, likely due to reduced light availability at the forest floor. For other groups, such as birds or lichens, responses were mixed and generally inconsistent.

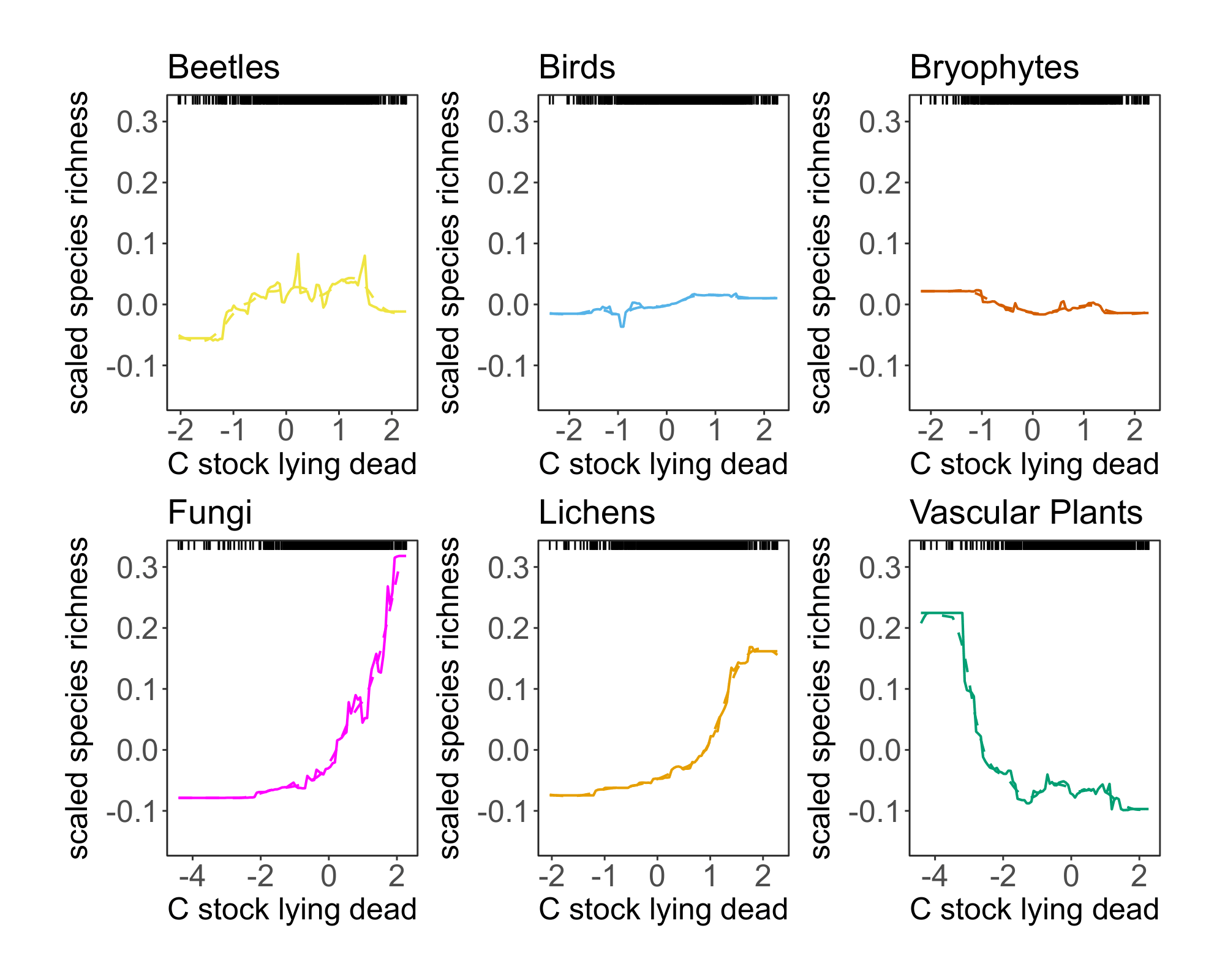

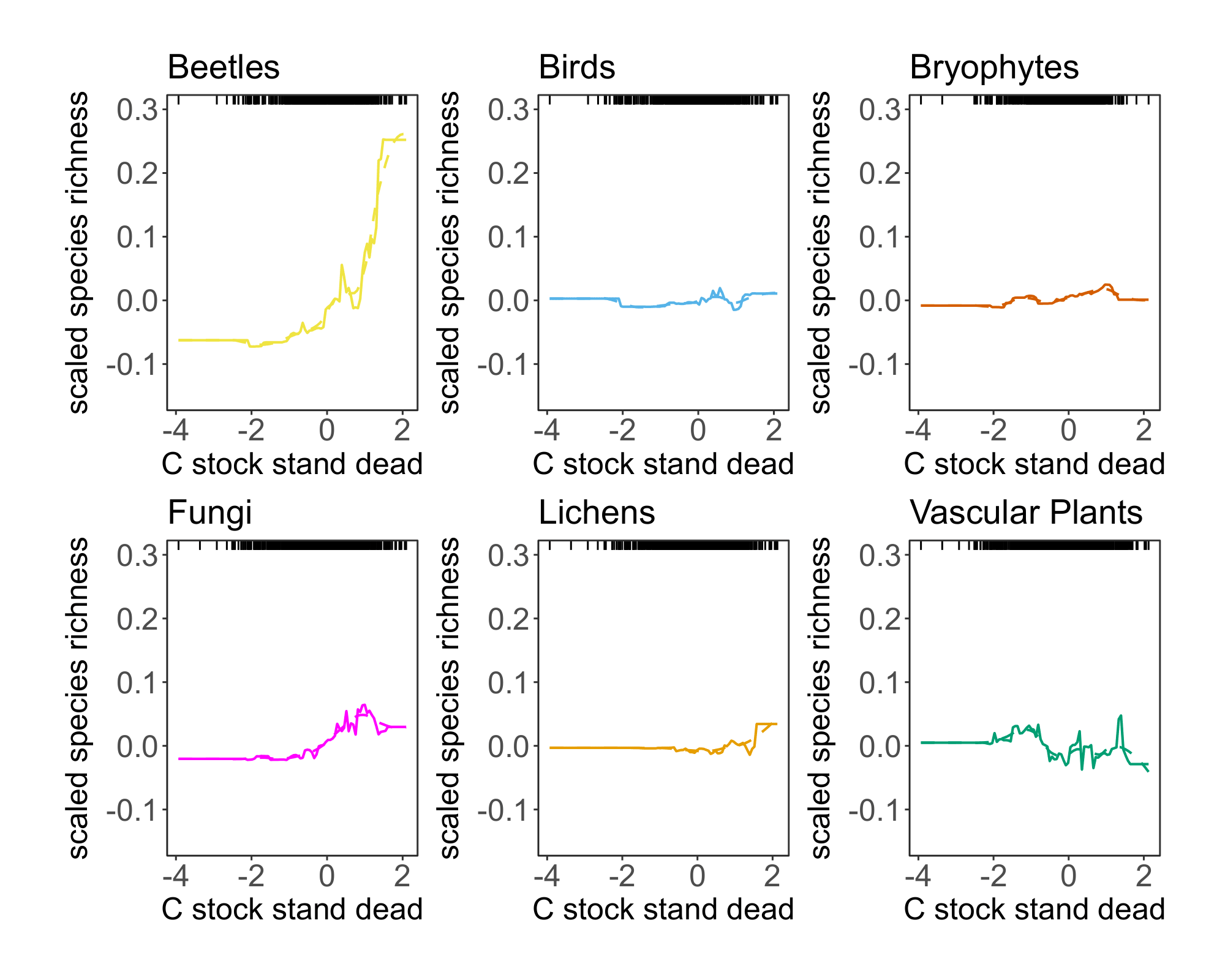

Deadwood told a whole different story. Carbon stored in standing and lying deadwood showed stronger and positive relationships with biodiversity, especially for fungi, lichens, and saproxylic beetles (Fig. 3, Fig. 4). In some cases, even relatively small amounts of deadwood carbon were associated with substantial increases in species richness. These findings highlight the ecological role of deadwood as both habitat and resource, supporting species that depend on structural complexity, stable microclimatic conditions, and ecological continuity.

These contrasting patterns have important implications for forest policy. By prioritizing carbon accumulation in living trees, current policy frameworks might promote fast-growing, structurally simplified stands to maximize carbon stocks in living trees. However, these approaches can often fail to support diverse biological communities. Our results suggest that aboveground living carbon is a poor surrogate for multi-taxon forest biodiversity and should not be treated as a standalone indicator of the ecological integrity of forest ecosystems. Conversely, deadwood emerged as a key component for aligning climate and biodiversity objectives. Deadwood supports biodiversity while also contributing to long-term carbon storage showing win-win outcomes for environmental policies.

Forests can contribute to both climate change mitigation and biodiversity conservation objectives, but only if policies move beyond a narrow focus on carbon in living trees. Recognizing the distinct ecological roles of different carbon pools, particularly deadwood, is essential for forest policies to minimise trade-offs while achieving both climate change mitigation and biodiversity conservation objectives.

Follow the Topic

-

Nature Communications

An open access, multidisciplinary journal dedicated to publishing high-quality research in all areas of the biological, health, physical, chemical and Earth sciences.

Related Collections

With Collections, you can get published faster and increase your visibility.

Women's Health

Publishing Model: Hybrid

Deadline: Ongoing

Advances in neurodegenerative diseases

Publishing Model: Hybrid

Deadline: Mar 24, 2026

Please sign in or register for FREE

If you are a registered user on Research Communities by Springer Nature, please sign in