The active layer soils of Greenlandic permafrost areas can function as important sinks for volatile organic compounds

Published in Earth & Environment

Permafrost, VOCs, and the atmosphere

Permafrost, ground that remains frozen for at least two consecutive years, is estimated to hold up to 1700 petagrams of carbon, which has accumulated over millennia as incompletely decomposed dead organic matter. This accounts for twice the carbon content of the atmosphere, making permafrost a considerable carbon reservoir. Climate change and rising global temperatures are accelerating permafrost thaw, mobilizing long-frozen organic matter. A portion of permafrost carbon is released into the atmosphere as greenhouse gases such as CO2 (carbon dioxide) and CH4 (methane). Thawing permafrost can also emit volatile organic compounds (VOCs), some of them highly chemically reactive. This may have profound atmospheric implications, as the VOCs are eventually oxidised, forming aerosol particles and reacting with hydroxyl radicals, processes that can alter the atmosphere’s reflectivity and cleansing capacity. Above permafrost lies the active layer, which undergoes seasonal freeze-thaw cycles, provides a rooting zone for plants, and can act as a near-surface ground water reservoir. With a depth that generally ranges between 40 to 320 cm, this layer supports an active microbial community, which plays central roles in the exchange of greenhouse gases and VOCs between the atmosphere and permafrost.

Greenland as the study site

In this study, we travelled to Greenland, which features extensive permafrost that is vulnerable to degradation from climate change. Since the end of the Little Ice Age, glaciers have been steadily retreating, with global warming accelerating this process. In glacial forefields, newly exposed areas transform through early plant succession and soil development. These young soils are characterized by notably different microbial communities than in older soils, with lower biomass and a higher proportion of bacteria relative to fungi. Within the active layer, the distribution of organic matter and microbial communities can vary across the vertical profile, with more abundant organic matter and biomass towards the surface. The combination of varying soil ages, diverse and contrasting microbial communities, and the presence of permafrost made Greenland a perfect site for studying how thawing permafrost influences soil processes.

As part of ongoing research projects at the University of Copenhagen, our team has been investigating the role of soil in VOC exchanges across different ecosystems. While some of our previous experiments have been conducted in temperate ecosystems, here we focused on colder, high latitude regions, characterized by active permafrost thaw. It is already well known that thawing permafrost releases large amounts of CO2 and methane, but much less is known about the release of VOCs. Previous studies suggest that the active layer might consume some of the VOCs released from permafrost, leading us to speculate about the manner in which these compounds exist and move through the soil.

The fieldwork

We designed a study that looked across the natural gradients in Greenland’s glacial forefields, and took measurements of VOC uptake and soil properties across different sites and soil depths to account for both vertical and successional differences. Travelling to remote places in the Arctic is always a bit challenging, and we ended up getting stuck at the airport in Greenland for a while because of the weather. However, the sampling itself went very smoothly. Sampling took place at two locations in western Greenland: Disko Island and Kangerlussuaq. It consisted of digging multiple soil pits and collecting density ring-samples at three different depths, and was carried out alongside setting up another experiment at the site, which involved setting up probes in the soil. The focus was on getting good quality samples, preserving them well, and transporting them back to Copenhagen for the actual experiment.

The lab work

Back from the trip, the soil samples were prepared for lab experiments under controlled conditions and field-relevant temperatures, designed to simulate the natural permafrost environment. We wanted to see both how the soils exchange VOCs with the air, and how they absorb different compounds. Samples were placed in glass jars with continuous clean synthetic airflow. For the VOC uptake experiment, a mixture of 12 common target VOCs was introduced into the airflow, allowing us to measure the rate at which the soil absorbs these compounds. The outflow was analyzed with a sensitive real-time VOC analyzer. On top of VOC measurements, we analyzed the key soil properties that impact microbial activity (carbon, nitrogen, phosphorus, water content and microbial biomass), helping establish links between VOC fluxes and soil characteristics.

What the soils revealed, and why it matters

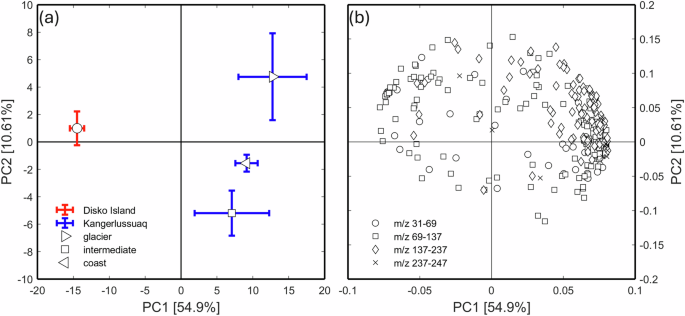

The study revealed that the active layer soils function as a “sink” for VOCs, absorbing the compounds passing through it, rather than emitting VOCs. This shows the potential for the active layer to intercept VOCs released from thawing permafrost below, before they escape into the atmosphere. This filtering effect was highest in the upper layers of the soil, where microbial activity and organic matter are most abundant. This and several other clues suggest that the active layer sink is mainly biotic, with microbial degradation likely being the main driver of VOC absorption. The analyzed soil properties varied significantly, and water content, organic matter, and microbial biomass were found to have the strongest correlations with VOC uptake. Adding water to the samples generally increased uptake, likely enhancing microbial activity or helping with VOC dissolution. The two sites, with different physiochemical characteristics, also exhibited distinct patterns. Younger soils closer to the continental glacier had lower overall VOC uptake rates, suggesting a strong link between VOC consumption and succession of the microbial community. Overall, the fact that the active layer can regulate how much of permafrost VOCs can get into the air was perhaps the most exciting finding. It was nice to see that our previous, and quite exploratory findings from past projects were confirmed in this more thoroughly designed experiment.

What’s next?

Considering that the active layer thickness has been observed to increase in almost all permafrost regions, not just in Greenland, its role as a sink and regulator for VOCs becomes increasingly relevant. A better understanding of these processes can also help improve climate models, giving us an insight into how permafrost thaw may change and shape the atmosphere in the future. A next step for us would be to disentangle how exactly the VOCs are absorbed and released, and which key microbes and metabolism processes are involved. There are still many unknowns, and continued research is important to better connect permafrost thaw, active layer soils, VOC exchanges, and their impacts on the atmosphere.

Follow the Topic

-

Communications Earth & Environment

An open access journal from Nature Portfolio that publishes high-quality research, reviews and commentary in the Earth, environmental and planetary sciences.

Related Collections

With Collections, you can get published faster and increase your visibility.

Archaeology & Environment

Publishing Model: Hybrid

Deadline: Mar 31, 2026

Drought

Publishing Model: Hybrid

Deadline: Mar 31, 2026

Please sign in or register for FREE

If you are a registered user on Research Communities by Springer Nature, please sign in