The dysregulated microbiome of city trees

Published in Ecology & Evolution

When I walk outside my apartment in Boston, Massachusetts, I am met by a lonely oak tree planted in a sidewalk pit. However, this tree is far from lonely – it plays host to a trillion microbial cells. As our own gut microbes help us digest food, absorb nutrients, and fight off pathogens, the microbial communities in soils, roots, and leaves regulate tree nutrition, metabolism, and immune systems. Boston, and hundreds of cities around the globe, are investing in planting trees like the one outside my apartment to provide much-needed shade and cooling services during the summer, collect air pollution on their leaves and improve the mental well-being of residents. Yet, these same environmental stressors that we need trees to protect us from also threaten tree health, and we haven’t developed a cohesive picture of how urbanization impacts the tree microbiome, or its potential influence on trees and the services they provide.

To better understand the impacts of urbanization on the tree microbiome, we at Boston University embarked on a study that took us from the hottest, least tree-covered neighborhoods of Boston to the shady, intact research plots at Harvard Forest to characterize the oak tree microbiome across a 120 km urban-to-rural gradient system. In the summer of 2021, we set out across Massachusetts to sample the leaves, soil, and roots from 91 oak trees – some tucked between the sidewalks and brownstones in Boston, others towering in Harvard Forest’s biomass inventory plots. We quickly learned that city soils can be as hard as concrete; by the end of the summer, we had broken three slide hammers trying to dig into them! But what kept us going were the people: curious residents would stop to ask what we were doing and shared their own stories about the trees—how long they’d been in the neighborhood, the shade they offered in the summer, or the loss when one didn’t survive. These conversations reminded us that our work wasn’t just about microbes or trees, but about how science could serve the communities living alongside them.

Back in the lab, I teamed up with a hard-working group of undergraduate research assistants. Together, we spent months getting DNA out of roots, leaves, and soils, celebrating at the sights of high concentrations of DNA after a successful extraction or groaning at the sight of a blank gel after a failed PCR. By the time we finally sent our samples for sequencing two years later, it felt like we had crossed the Boston Marathon finish line, but the real excitement was only just beginning.

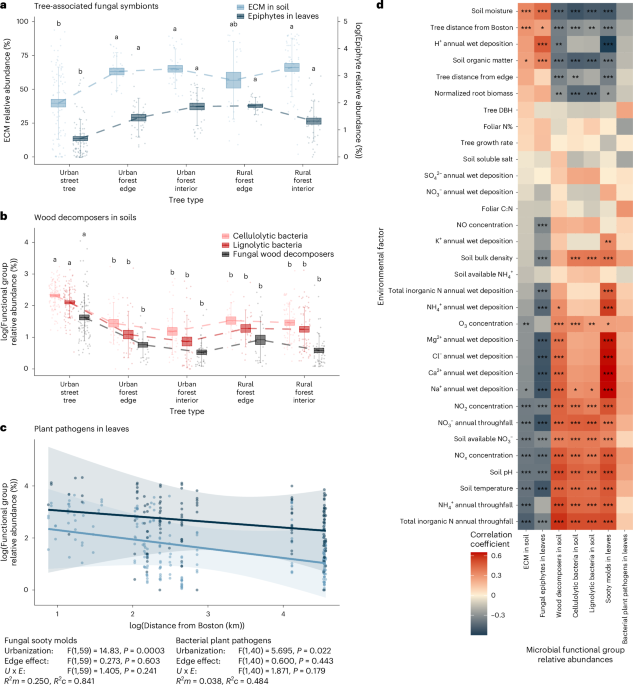

Some of our results lined up with our expectations, but others changed the way we think about urban trees and their microbiomes. First, as we had found in a previous study of forest soils along an urban-to-rural gradient, we found that our city oak trees had a lower abundance of microbial symbionts, or the microbes that help trees take up nutrients and tolerate stress. Instead, plant decomposers and pathogens thrived in the city. Wood decomposer abundances increased in the soils of city tree pits, potentially acting as root pathogens. In fact, our city oak trees collected not only plant pathogens, but also animal and human pathogens across their leaves, soils, and roots! These pathogens were associated with high soil temperatures and high levels of atmospheric pollution, as well as low soil moisture, all characteristic of urban areas – the same factors that were negatively associated with the tree symbionts. City oak trees also accumulated denitrifying bacteria and fungal decomposers that could accelerate the production of greenhouse gases. Total microbial diversity was lower in urban compared to rural trees, across their entire microbiome, which has been previously correlated with the prevalence of inflammatory diseases, including asthma and allergies, in nearby human populations.

These results have important implications for the health of not only city trees, but also city residents. Our results suggest that street trees’ most important functions in urban settings, such as the sequestration of carbon dioxide and promotion of residents’ health and well-being, may be partially offset by the composition and functions of their microbiomes. However, there is hope: our results suggest that some tree-level management interventions investigated by previous studies, such as adding compost to urban trees, can foster conditions that maintain diverse and beneficial microbial communities in urban areas. From the residents who stopped to share memories to the students who poured their energy into the lab work, this project reminded me that urban trees connect not only microbes and ecosystems, but also communities and people. And ultimately, it is this human connection that will determine how we protect and sustain the trees that protect and sustain us.

Follow the Topic

-

Nature Cities

This journal aims to deepen and integrate basic and applied understanding of the character and dynamics of cities, including their roles, impacts and influences — past, present and future.

Please sign in or register for FREE

If you are a registered user on Research Communities by Springer Nature, please sign in