Why is Singapore Identified in Global Research as Number One? How Physical Activity and Education Excellence Created a Global Leader

Published in Sustainability

By Allison Perrigo1,2, Emke Vrasdonk1,3, Louisa Durkin1 and Alexandre Antonelli1,2,4

1Gothenburg Global Biodiversity Centre, Sweden

2Department of Biological and Environmental Sciences, University of Gothenburg, Sweden

3Environmental Systems Analysis, Department of Technology Management and Economics, Chalmers University of Technology, Gothenburg, Sweden

4Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew, Richmond, United Kingdom

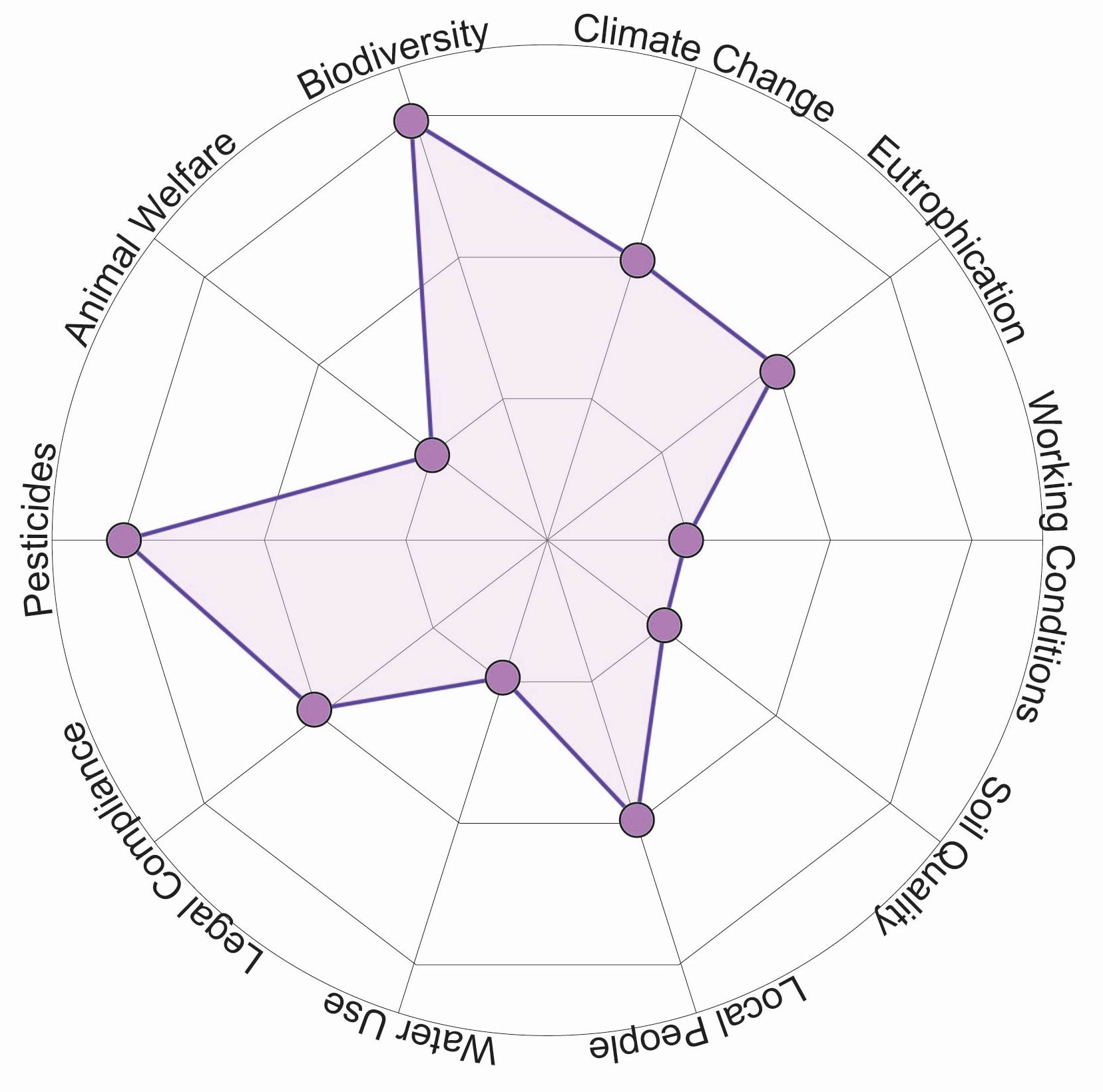

Swedish giant supermarket chain Coop announced in their Sustainability Declaration that all of their 17,000 in-house products will soon have a full socio-environmental impact disclosed on the package. This move follows an increasing trend in ecolabels, but stands out in its attempt to convey ten disparate variables in a simple graph. Among the variables are climate impact, biodiversity impact, animal rights, water use and working conditions.

We fully support initiatives to give consumers the possibility to make more informed decisions and that consolidate a significant amount of information into a single figure. Still, we feel it is important to look critically at this first effort, as it will set a bar for future efforts in Sweden and internationally. Here we explore the background to this initiative and its potential shortcomings, followed by recommendations for improvement. In particular, we focus on one of the ten parameters Coop will evaluate: biodiversity.

It’s fair to assume that environmentally-minded consumers want to ‘do the right thing’. The practical question, however, is which product to choose in the few seconds we spend in front of a filled supermarket shelf before moving on to the next item. Ecolabels are one way to streamline this process.

The first eco-label, ‘Blue Angel,’ was introduced in Germany in the late 1970s. Since then, the environmental impact of individual products has become increasingly visible to allow consumers to make informed choices. Significant political action has been taken to facilitate the use of labelling schemes, introducing common legal frameworks and international standards.

Consumers today are met with a proliferation of labeling systems. Coop alone boasts at least 19 different labelling systems on their products, and although this figure seems high it’s just a fraction of the nearly 460 ecolabels currently in use. The breadth of labels is potentially a sign of a diverse and developed market for sustainable products, but it can also lead to confusion for us as consumers. An increasing array of labels is difficult to contain and complicates interpretation if they convey inconsistent messages. Because of this, the plurality of labelling schemes undermines the original idea of a clear-cut signal.

Since most labels are simply present or absent, it can be tricky for the consumer to really understand the relative impact products may have compared to one another. Are two products bearing the same label equivalent in their production? Probably not, but they will both presumably meet a minimum standard.

There are methods that can be used to give consumers more information in order to understand the relative impacts of a product. Life cycle assessments are a widely used tool that evaluate the potential environmental impacts of products from raw-material acquisition to end-of-life treatment. A simplified version of this is the basis of the ‘product carbon footprint’ that is used as the parameter for climate impacts in Coop’s labelling scheme.

The product carbon footprint measures the overall amount of carbon dioxide (CO2) and other greenhouse gas emissions (e.g. methane and nitrous oxide) associated with the product throughout its lifecycle. All greenhouse gas emissions are expressed in the amount of CO2 that would have an equivalent global warming impact, which is called a CO2-equivalency factor. This allows for combining impacts occurring at different steps of the supply chain and at different geographical locations. Calculating CO2 equivalents based on a standardized product unit (for example 1 kg of bone-free meat) gives a reasonable basis for comparison with different production systems.

As the proposed Coop system highlights, many factors beyond carbon emissions are also relevant to how sustainable a product is. But many of these other sustainability factors—for example biodiversity—cannot currently be summarized in a straight-forward and value-free way through equivalency factors.

Coop has decided to form their new label as “spider web charts,” also known as radar or polar charts. There are several advantages of using these charts in this way:

As usual, the devil is in the details. We identify three particular pitfalls which require careful consideration and close collaboration between the research community and industry.

For certain parameters such as climate change, there is methodology in place to assess contributing factors in a standardized way. However, such metrics do not exist for all of the parameters presented in Coop’s new labeling scheme so proxies must be used.

There is currently no standard metric to determine the biodiversity impact of a product. Although some of Coop’s internationally recognized data sources are indicated (including the World Bank, World Wildlife Fund, and the Business Social Compliance Initiative) it is not entirely clear exactly which data is used or how. It appears that Coop will give its biodiversity rating based solely on each product’s country of origin* based on Yale’s Environmental Performance Index. But biodiversity is accounted for on multiple levels—genetic, species and ecosystem-level diversity—and relying solely on the country of origin will not reflect threats to biodiversity at these different levels.

Terrestrial biodiversity loss is driven in large part by land-use change. There are tools and databases (such as Trase and FABIO) that are beginning to track land use change attributed to different crops with increasing precision. The complexity involved in tracing land use naturally leads to simplifications, but by using these more accurate forms of land use tracing it could be ensured that labels are not so extreme as to discourage efforts to increase local sustainability initiatives within otherwise poorly performing countries.

*We requested further clarification of the methodology from Coop, but as of the publication of this blog we are still awaiting an answer.

Many of the ten parameters suggested in this labeling system directly affect one another, and it is unclear how or if this will be reflected in the labels. For example, both climate and pollution are among the top direct drivers of biodiversity loss. So should low marks in one or either of these automatically give the product a low mark for biodiversity as well? In the example product label released by Coop, a middling mark for climate is shown, but near top marks for biodiversity. It is unclear if the interaction is considered based on this single label.

Looking beyond biodiversity, other questions arise. Soil quality, eutrophication, chemical use and water quality are inextricably linked, how will this be reflected? And perhaps most importantly, how will the factor “law compliance and traceability” be treated? If we don’t know where a product originated then it becomes impossible to give an accurate assessment of nearly any of the subsequent sustainability indicators.

Is the extinction of pandas worse than a 0.5℃ increase in temperature, or the unfair treatment of Ethiopian workers? There’s no objective, mathematical solution to this problem – this is a philosophical question, one that compares apples and oranges. It could be argued that scaling each social-environmental parameter to one would be a sensible approach, which is the route that it seems Coop has taken – however this is itself a major and hidden value judgement.

The leading standards for life cycle assessment specify that you cannot use weighing for comparative assertions intended to be disclosed to the public. This makes sense, since most consumers are not experts and will not know the implications of seeing a single, weighted environmental impact score. The spider web diagram leaves it completely up to the consumer to choose the aspects they think are more important – which complicates their decision and undermines the idea of a ‘simple’ label.

A more informed solution might be to weigh impacts in relation to the ‘planetary boundaries’ concept. Under this logic, an impact in a globally critical variable – such as biodiversity loss – could be argued to carry more importance than in another aspect, such as freshwater use. However, this omits social aspects of sustainability and further the spider web diagram may become unbalanced.

One could argue that a partial step in the right direction is better than no step. We agree, as long as it doesn’t mean that the job is done. We therefore endorse the initiative in its goal of capturing additional variables beyond climate, but we recommend both Coop and other companies considering similar initiatives to:

In summary, while we welcome this effort and see it as an important first step in understanding and improving our purchases from a consumer perspective, we hope that it continues to improve and grow as a dynamic and research-based system that leads to more environmentally-friendly consumption and helps us safeguard the world’s biodiversity.

An introduction to Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) Topics and their role in highlighting sustainable development research.

Continue reading announcement Read more

We use cookies to ensure the functionality of our website, to personalize content and advertising, to provide social media features, and to analyze our traffic. If you allow us to do so, we also inform our social media, advertising and analysis partners about your use of our website. You can decide for yourself which categories you want to deny or allow. Please note that based on your settings not all functionalities of the site are available.

Further information can be found in our privacy policy.

Please sign in or register for FREE

If you are a registered user on Research Communities by Springer Nature, please sign in