The multifunctional gene engineering platform CRISPR to dissect the genetic code of life

Published in Bioengineering & Biotechnology, Materials, and Microbiology

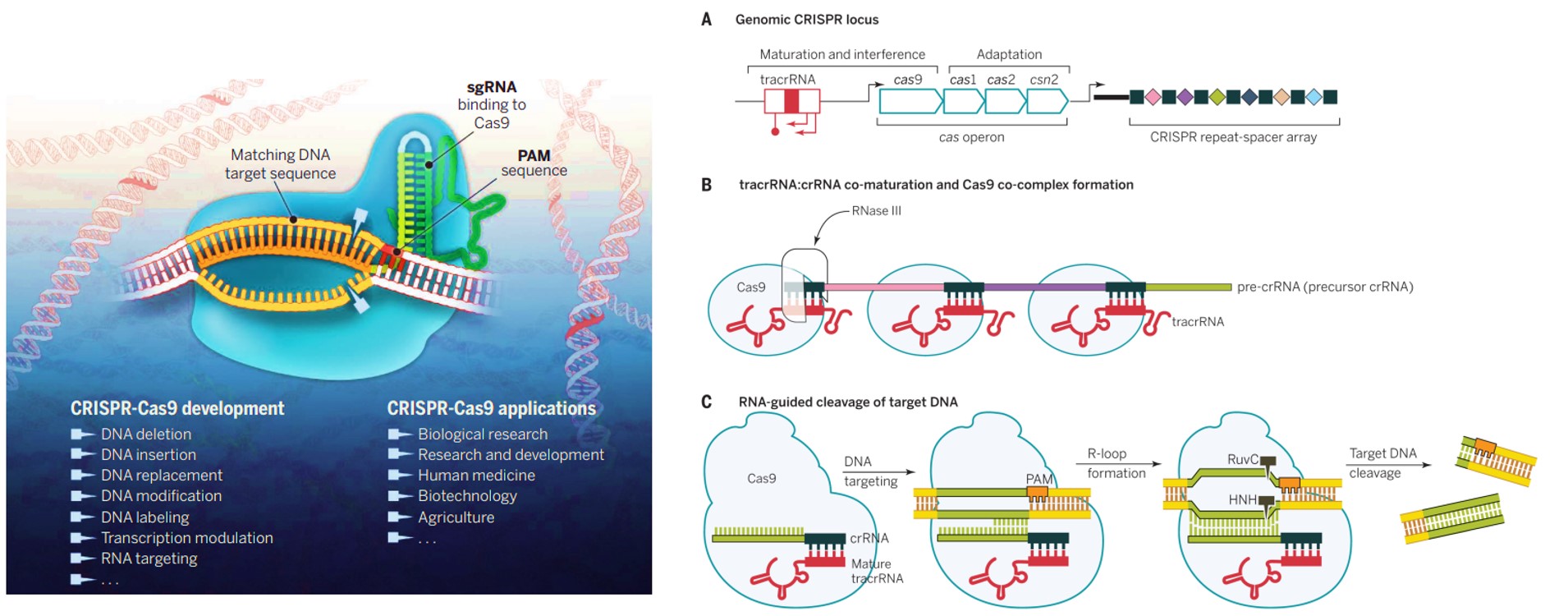

Having recently read the “code breaker” by Walter Isaacson that details the life and times of Jennifer Doudna, the gene editing pioneer, whose breakthrough work originated from dissecting the genetic code of life. To write this article, I ventured from my usual interests, to revisit the gene-engineering work of the pair – Doudna and Emmanuel Charpentier who jointly won the Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 2020 by developing a "programmable method" for genome editing. During their early years of research, the pair studied a prokaryotic adaptive immune defense system that targeted invading viruses through a sequence-specific immune mechanism. This adaptive immunity in prokaryotes is facilitated via “clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats – with the Cas9 protein,” commonly abbreviated as CRISPR-Cas9. The scientists then repurposed this gene editing mechanism within eukaryotic cell lines for innovative applications in and beyond the lab (Figure 1) [Doudna J. and Charpentier E. 2014].

- A brief review of CRISPR gene editing and a brief introduction to its history,

- The role of CRISPR in genetics screens to understand underlying pathologies,

- The interdisciplinarity of CRISPR across neuroscience, cardiology, and oncology,

- The treatment of rare hematological disorders with CRISPR, and

- AI-based CRISPR strategies to optimize the protocol in the life sciences [Golkar Z. 2020].

Figure 2: The basics of CRISPR in brevia – A) an overview of the CRISPR-Cas9 system as it occurs in prokaryotes. The CRISPR loci are found in roughly 40 percent of bacterial genomes and can be transmitted both horizontally and vertically. B) Translating CRISPR-Cas9 as a precise genome editing tool in eukaryotic cell lines. C) An excerpt of the correspondence between the experimentalists Ruud Jansen and Francisco Mojica that led to the origin of the ‘snappy’ term CRISPR (clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats) [Golkar Z. 2020, Davies K. and Mojica F. 2018].

What is CRISPR (Clustered Regularly Interspaced Short Palindrome Repeats)?

While CRISPR needs no introduction to basic scientists in the field of gene engineering and the life sciences – CRISPR or ‘clustered regularly interspaced short palindrome repeats’ is derived from a naturally occurring genome editing adaptive immune defense system found in bacteria [Xu Y. and Li Z., 2020]. Geneticists and bioengineers have repurposed this technology to selectively modify DNA of mammalian cells or living organisms with adaptations for laboratory use. In general, during its mechanism-of-action, the bacterial CRISPR system is somewhat akin to the human immune system. Much like when we generate an immune response to a viral infection in the form of masses of antibodies that then form immune memory. Similarly, when a virus or phage infects bacteria, CRISPR assists to establish genetic memory as the bacterium incorporates or inserts a piece of the viral genome into its own genome.

This newly acquired DNA sequence facilitates the development of a new “guide RNA (gRNA)” sequence for CRISPR to find the invader via sequence complementarity. Thereby when a virus re-infects a bacterial cell, the guide RNA will rapidly recognize that viral DNA sequence to bind and destroy it. This system is broadly classified into two classes – Class I multiprotein complexes (inclusive of type I, III and IV), and class II single protein nuclease complexes (inclusive of type II, V and VI) [You L. et al. 2019]. The CRISPR-Cas9 technology specifically originates from type II CRISPR-Cas systems that naturally provides bacteria with adaptive immunity towards viruses and plasmids [Doudna J. and Charpentier E. 2014].

The CRISPR-associated protein Cas9, for instance is an endonuclease that incorporates a guide sequence within an RNA duplex to introduce double-strand breaks into the DNA, to efficiently conduct its mechanism-of-action (Figure 1). Conversely, anti-CRISPR proteins also exist as components that are naturally expressed by bacteriophages (viruses) to inhibit the adaptive immunity exerted by prokaryotes. These fortuitous “natural brakes” are also translated in-lab for safer and optimized gene editing mechanisms that limit off-target effects (Figure 3) [Zhang F. et al. 2019].

Figure 3: Anti-CRISPR (Acr) proteins, their applications and regulation. The Anti-CRISPRs can regulate the CRISPR-Cas system in many diverse scenarios including gene editing, gene regulation, epigenetic modification, and DNA imaging. The Acr proteins can in turn be regulated using inducible promoters, tissue specific microRNAs (miRNAs) and small molecules to achieve rapid and dynamic regulation of CRISPR-Cas activity [Marino N. et al. 2020]

The history of CRISPR – a timeline of key events

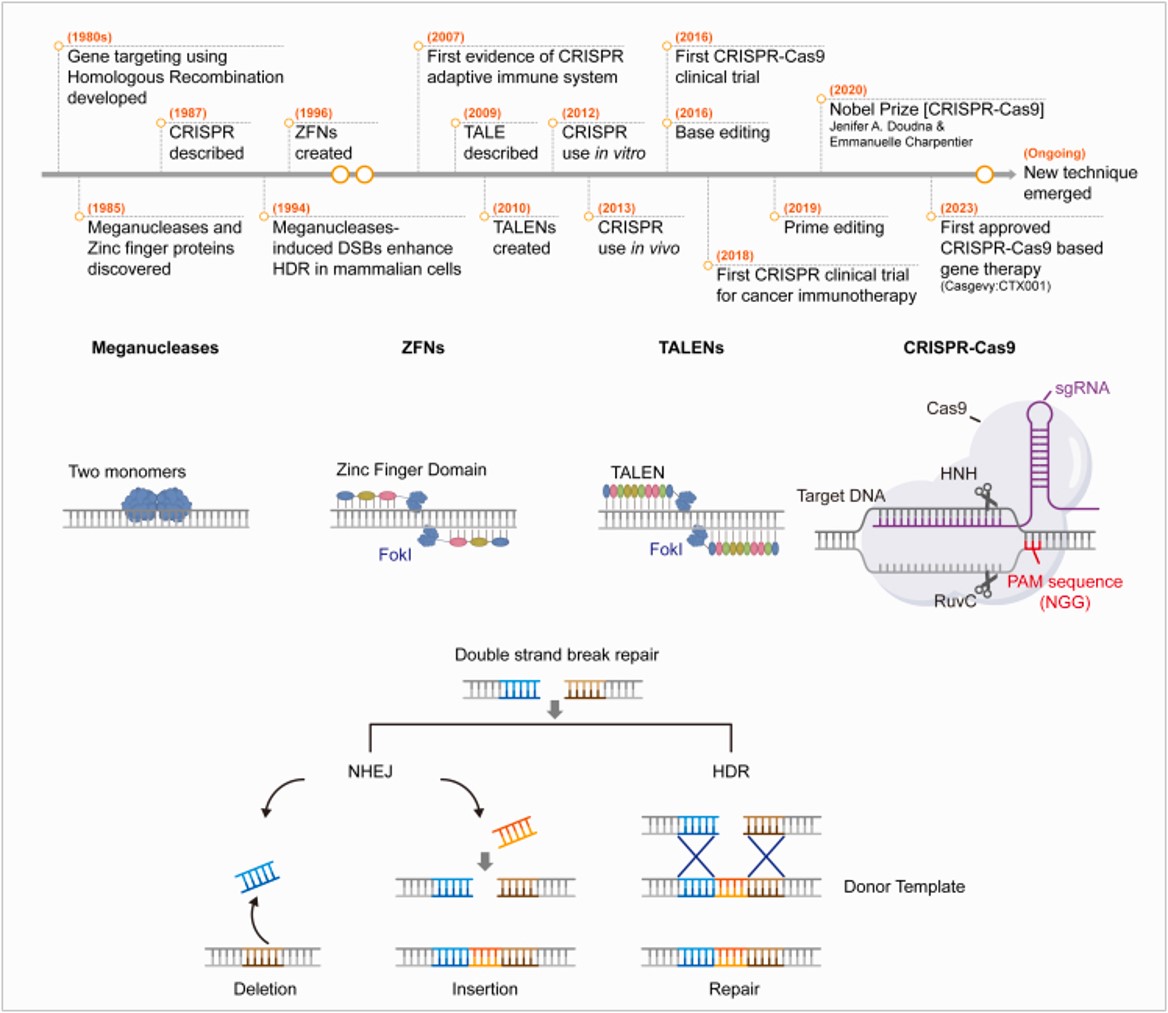

Genome editing has at present substantially advanced in the clinical context, with applications for disease treatment and cure, by delivering genome editors into the nucleus of target cells through enveloped gene delivery vehicles [Ngo W. et al. 2025]. These progressive quantum leaps in genetics medicine are more so accentuated by the fact that this underlying discovery occurred relatively not so long ago. In 1987, Japanese scientists at the Osaka University led by Yoshimi Ishino made a foundational observation of unusual repetitive DNA sequences while studying the E. coli gene, whose functional significance was not understood at the time [Ishino Y. et al. 1987], until approximately 20 years later. In 1993, experimentalists Francisco Mojica in correspondence with Ruud Jansen, coined the term "CRISPR," based on its function as a microbial adaptive immune system (Figure 2) [Mojica F. et al. 2005, Davies K. and Mojica F. 2018]. Biologist Alexander Bolotin is subsequently credited with discovering the Cas gene in May 2005 by recognizing that CRISPRs have spacers of extrachromosomal origin [Bolotin A. et al. 2005].

Figure 4: A timeline of key events during the discovery and application of the CRISPR system. Genome editing platforms and DSB repair mechanisms (A) Schematic timeline of the development of gene editing. (B) Overview of four currently used genome editing technologies: Meganucleases; ZFN, zinc finger nuclease; TALEN, transcription activator-like effector nuclease; CRISPR-Cas9, clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats and CRISPR-associated protein 9 (Cas9). (C) DSB repair mechanisms. DSBs formed by genome editing are repaired through non-homologous end joining (NHEJ) or homology-directed repair (HDR) using a donor template. NHEJ can lead to insertions or deletions of various lengths, whereas HDR can induce gene replacement when a donor DNA template is present. NHEJ, non-homologous end joining; HDR, homology-directed repair. Credit: [Joo J. et al. 2025].

In 2006, Biologist Eugene Koonin proposed the hypothetical scheme of adaptive immunity for CRISPR cascades to function as a bacterial immune system. By March 2007, an unconventional breakthrough occurred in the food industry, to experimentally demonstrate the CRISPR adaptive immunity, when scientists at Danisco explored the capacity of S. thermophilus to respond to a phage attack – a common issue that affects the quality of industrial yoghurt making. When the new phage/viral DNA was integrated into the CRISPR array, it fought off the next wave of an attacking phage, to implicate its function as a bacterial immune system [Barrangou R. et al. 2007]. Later, in 2008, geneticist John van der Oost and colleagues pieced together critical information to show that in E. coli, the spacer sequences derived from phage are transcribed into small RNAs known as CRISPR RNAs (crRNAs) to guide the Cas protein to the target DNA to acquire viral resistance [Brouns S et al. 2008, Gostimskaya I 2022].

These series of serendipitous discoveries led scientists to speedily piece together diverse details about the CRISPR-Cas system’s interference with an invading phage through time to integrate its repertoire of distinct proteins and eventually repurpose the mechanism in basic sciences, molecular biology, biotechnology, and clinical medicine. The CRISPR discovery pipeline as elaborated on the website of the Broad Institute, is complex, fastidious, and marked by key discoveries and contributions of many significant scientists within diverse fields, across a short timeframe as schematically represented herein (Figure 4) [Golkar Z. 2020, Joo J. et al. 2025].

The Interdisciplinarity of CRISPR – News and Opinions

Figure 5: Outlining the interdisciplinary promise of CRISPR in immunotherapy and immunomaterials to deliver genes through biomaterials for efficient precision medicine efforts. Credit: Jeewandara T. 2023

While I have previously covered foundational interdisciplinary CRISPR advances on many different news platforms in depth through the years, including notes on the CRISPR interference protocol (CRISPRi) to describe a gene expression knockdown mechanism with a deactivated Cas9 (dCas9) protein, and generalized the applications of CRISPR in biomaterials for immunotherapy (Figure 5). The technology can also combine other gene editing methods such as multiplex automated genome engineering in biotechnology to herald a new era in synthetic biology.

Interdisciplinary applications broadly vary across CRISPR-Cas9 based methods of metabolic engineering, inclusive of CRISPR-powered optothermal nanotweezers, while advances include deep learning models for AI-based CRISPR protocol optimization. Further articles that I wrote, shed light on how the technology can incorporate novel proteins such as CRISPR-Csm as a type III CRISPR-Cas interference complex for advanced precision RNA editing [You L. et al. 2019], which transcends mechanisms of CRISPR interference (CRISPRi). CRISPR can even influence new paradigms of immunoengineering biomaterials as immunomodulators in vivo. And effectively bioengineer humoral immunity by producing CRISPR-engineered B cells, with scope to create genetically engineered vaccines against HIV, Influenza, and the Epstein-Barr virus, with added capacity to develop disease therapies for which long-term treatments or cures do not yet exist.

To add further nuance to its already versatile portfolio; applications of CRISPR are also observed in spatial transcriptomics [Binan L. et al. 2025] and in clinical applications to treat rare diseases [Li T. et al. 2023]. Complex approaches integrate single-cell transcriptomics or spatial transcriptomics simultaneously with CRISPR screening to reveal intracellular, intercellular, and functional transcriptional circuits associated with diseases [Binan L. et al. 2025]. This is followed by CRISPR-Cas9 therapeutics-associated treatment strategies presently in development from the bench-to-clinic to correct or disrupt disease-causing rare genes with precision and efficacy to treat several rare diseases [Jiang C. et al. 2020, Heidenreich M. and Zhang F. 2015].

CRISPR Screening – Investigating the molecular underpinnings of pathology

CRISPR screening is a powerful and versatile method to understand the genetics underpinning biological pathways at a systems level via functional genetic screens of the CRISPR-Cas9 system (Figure 6) [Bock C. et al. 2022]. The protocol can generate genome-wide perturbations or disturbances, by integrating CRISPR knockout, CRISPR interference, or CRISPR activation mechanisms to deactivate or enhance gene expression via loss- and gain-of-function protocols, respectively. Either version of the gene editing protocol (loss- or gain-of-function modalities) facilitates genetic perturbation to manipulate a gene of interest in a molecular pathway, or a gene of interest involved with a disease state of interest. By using CRISPR-screening, the pooled loss-of-function data for instance can identify genetic mechanisms that underly a variety of pathologies, including.

- The enhanced growth rate of metastatic tumors [Chen S. et al. 2015],

- Identify genes responsible for drug resistance [Kerek E. et al. 2021], and

- Identify the host-infection rates during viral infections [Li B. et al. 2020].

This intricate method can map gene circuits within cells to determine causal connections between the expression of a gene and its downstream signaling pathways (Figure 7) [Binan L. et al. 2025, Dixit A. et al. 2016]. Intercellular genetic interactions can be deciphered during CRISPR screening by recording the gene expression rates via guide RNA (gRNA)-based perturbations. The gRNA-sequencing is a key aspect of CRISPR, and it can be coupled to imaging-based profiling methods to effectively measure gene expression best suited to understand pathological associations at the genetic level [Feldman D. et al. 2022].

Innovative methods that thus measure gene expression include “Perturb-FISH (fluorescence in situ hybridization)” an imaging method developed in molecular biology to visualize the CRISPR-knockout effects of gRNA-linked perturbation. Specific examples include CRISPR inhibition (CRISPRi) screening in autism spectrum disorder (ASD)-linked risk genes conducted with human-induced pluripotent stem cell (hiPSCs) astrocytes [Binan L. et al. 2025]. Such imaging methods can simplify the observations of common calcium activity in the cells, alongside genetic interaction associations in order to identify dysregulated pathways, to study genetic and molecular trends in astrocytes at single-cell resolution. These efforts offer transcriptome insights to understand and treat several disorders [Quesnel-Vallieres M. et al. 2019, Wang Q. et al. 2021].

Genetics screening in the tumor microenvironment with CRISPR

The screening method is equally applicable to record the effects of knockout perturbations (induced via CRISPR knockout) in a tumor xenograft, to interrogate complex genetic interactions between tumor cells and the infiltrating immune cells, to understand molecular pathway associations in the tumor microenvironment. Measures of genetic perturbations can answer specific queries – such as how does nuclear factor kB (NF-kB) pathway influence tumor-related inflammation? (Figure 8) [Binan L. et al. 2025]. These combined methods in functional genomics shed light on the intracellular circuitry in molecular detail, inclusive of immuno-oncology panels of tumor cells to examine immune responses to cancer progression in animal models [Binan L. et al. 2025, Jaitin D. et al. 2016].

Applications of CRISPR – from the lab to the clinic

CRISPR for neuroscientists

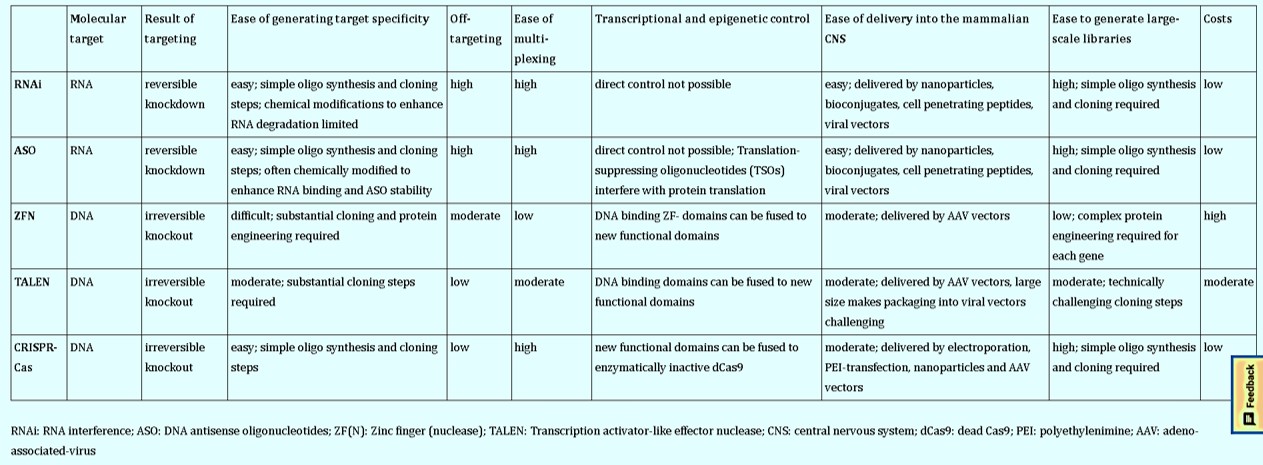

Broader examples of gene editing advances from the lab to the clinic highlight the versatility of CRISPR across multiple disciplines. In neuroscience, for example, the complexity of the mammalian brain is initially investigated in non-human animal models to understand cellular and molecular underpinnings of brain disorders [Heidenreich M. and Zhang F. 2015]. Existing gold-standard gene silencing methods such as RNA interference (RNAi) facilitate the study of gene function in pre-clinical animal models and in cell cultures [Elbashir S. et al. 2001, Hammel J. et al. 2003]. RNA interference (RNAi) is generally a prospective tool to determine human viral infections [Levanova A. and Poranen M. 2018]. However, CRISPR advances have seen to the introduction of genome editing based on engineered designer nucleases to offer several advantages beyond RNAi in neuroscience.

Overall, the gene editing portfolio broadly includes tools based on site-specific DNA nucleases such as zinc-finger nucleases (ZFNs) and transcription activator-like effector nucleases (TALENs). Alternative methods based on DNA anti-sense oligonucleotides (ASOs) and RNA interference (RNAi) can be incorporated for gene silencing (Figure 4) with promising therapeutic implications to suppress pathogenic protein aggregates in the brain [Smith R. et al. 2006, Kordasiewicz H. et al. 2012]. The ASO therapy can target specific disease mechanisms as a powerful way to treat neurodegenerative disorders such as amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), Huntington’s and Alzheimer’s by reducing the associated toxic proteins via its delivery to the central nervous system.

Several gene editing tools exist for refined gene regulation, beyond a simple gene knockdown status (Table 1) to understand molecular underpinnings of the nervous system, in general (Figure 9) [Heidenreich M. and Zhang F. 2015, Geurts A. et al. 2010]. Technically, a nuclease-inactivated version of Cas9 (dCas9 or deadCas9) can fuse with diverse functional enzymatic domains to mediate transcriptional regulation in the form CRISPR-interference [Gilbert L. et al. 2013].

Figure 9: Methods to generate genetically modified rodents. Comparison of the timelines of traditional gene targeting using classic homologous recombination (HR) in embryonic stem cells (ESCs) or in Cas9, in one-cell embryos. (a) The HR-approach is time- and cost-intensive. (b) By contrast, the Cas9/sgRNA microinjection is relatively easy and fast without genetic backcrossing and crossbreeding. Credit: [Heidenreich M. and Zhang F. 2015].

Neuroepigenetics

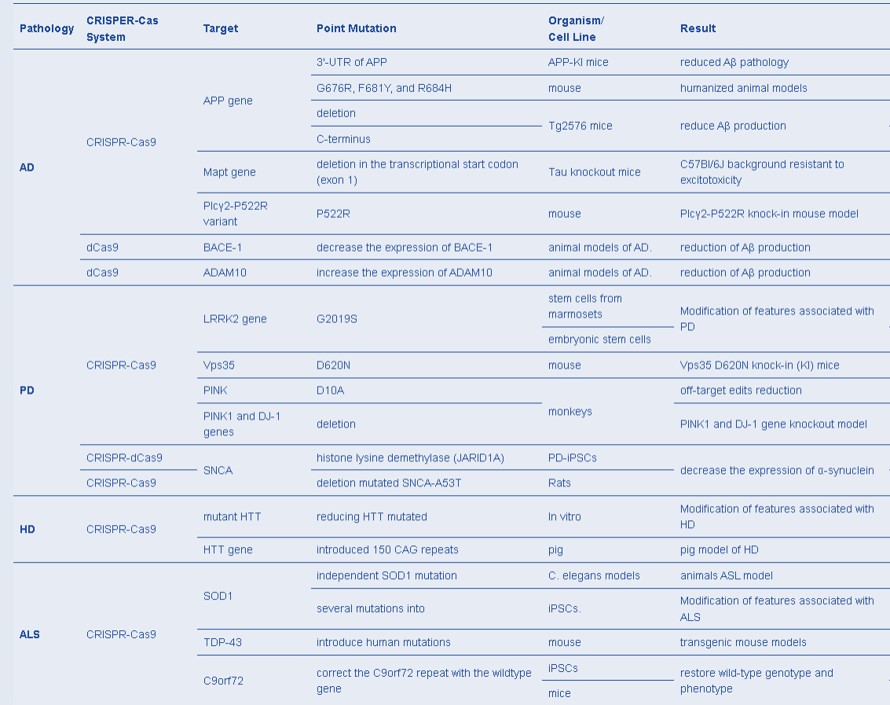

Recent investigations of CRISPR advances in neuroscience have used Cas proteins to edit the epigenome, to potentially treat a variety of neurological disorders such as Alzheimer’s disease, Parkinson’s, and autism, by better understanding their mechanisms-of-action [Heidenreich M. and Zhang F. 2015]. Four of the most diffuse neurodegenerative disorders include Alzheimer’s disease, Parkinson’s disease, Huntington’s disease, and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) [Plano L. et al. 2022]. Several implementations of the CRISPR-Cas system have facilitated humanized animal models to understand these disease mechanisms, in order to optimize treatment strategies from the bench-to-clinic (Table 2) [Serneels L. et al. 2020, Wulansari N. et al. 2021, Plano L. et al. 2022].

The new frontier in cardiology - CRISPR correcting cardiovascular disease

In cardiology, the predominant in vivo gene editing technique that is in use in animal models to induce knockout and knock-in technologies is the Cre-LoxP recombination system. The advanced capacity to correct genetic drivers of cardiovascular disease by delivering gene editing components in vivo via CRISPR, in order to permanently treat human patients is therefore an exciting new therapeutic frontier on par with science fiction. CRISPR aims to uncover the mechanistic underpinnings of congenital heart disease, adult cardiovascular disease, and inherited cardiomyopathy to attenuate cardiovascular disease in humans [Lewandoski M. 2001, Doetschman T and Azhar M. 2012].

In 1994, cardiology researchers showed the capacity to introduce double-strand breaks into the genome of mouse cells via the expression of a rare cutting endonuclease and integrate the targeted genes efficiently, which led to generating site-specific double-strand breaks [Rouet P. et al. 1994]. Of the clusters of endonucleases, the RNA-guided CRISPR-Cas system is shown to simplify the gene editing method, with enzymes from Cas9 to Cas13 that can transform the accessibility of genome engineering across DNA to RNA (Figure 10) [Knott G. and Doudna J. 2018]. The defense system better adopted for use in eukaryotic cell lines for DNA cleavage and gene editing is the class II CRISPR-Cas system, which allows reduced off-target editing of the genome, in addition to the widely integrated type II-A subtype Streptococcus pyogenes Cas 9 protein (Figure 11) [Liu N. and Olson E. 2022, Joo J. et al. 2025, Anzalone A. et al. 2020].

Figure 11: The mechanisms of base editing and prime editing systems in precision gene editing. Base editing involves the fusion of Cas9 nickase (nCas9) with nucleo-base modifying enzyme to convert one nucleotide into another without generating double-strand breaks. This technique is useful to introduce specific point mutations, precise gene corrections, or stop codons for gene knockout. Prime editing integrates nCas9 with reverse transcriptase and employs prime editing guide RNA (pegRNA) that contains a single guide RNA (sgRNA), a reverse transcriptase template (RTT) and a prime binding site (PBS). Prime editing allows the insertion, deletion, or replacement of short DNA sequences. RNA editing uses Cas13 nuclease fused to a deaminase enzyme to alter the RNA sequences and thereby modify protein production. Transcriptional modulators regulate gene transcription using catalytically inactive Cas9 (dCas9) fused to transcriptional modulation domains [Joo J. et al. 2025].

A new era in cardiovascular gene editing for precision therapeutics

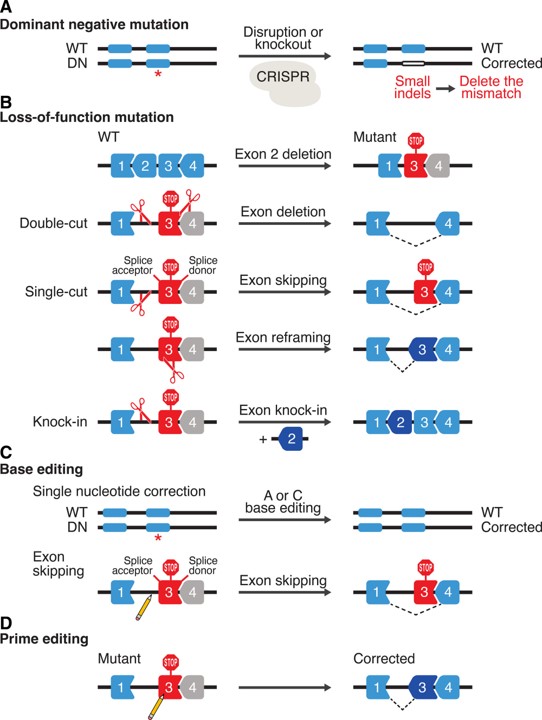

The CRISPR-Cas9 genome editing tools are foundational for therapeutic applications at the genetics level, as they can induce permanent changes within the genome to result in life-long therapeutic effects in heart disease. A variety of gene engineering strategies exist to treat inherited cardiomyopathies and monogenic cardiovascular diseases caused by single gene mutations (Figure 12) in pre-clinical models, inclusive of:

- The correction of dominant-negative mutations with CRISPR-Cas9 to delete mutations by inducing small insertions or deletions (i.e. INDELS)

- The restoration of loss-of-function mutations that occurs due to the deletion of an exon resulting in a downstream frameshift, which can be corrected by double-cut, single-cut, or knock-in strategies.

- Base-editing to correct specific single nucleotide mutations, and

- Prime editing to correct all possible single nucleotide mutations and induce small deletions and insertions (Figure 11) [Joo J. et al. 2025].

Figure 12: Strategies for therapeutic genome editing by CRISPR-Cas. A Dominant-negative (DN) mutations can be corrected by CRISPR-Cas9 to delete the mutations by inducing small insertions or deletions (INDELs). B, an example of a loss-of-function mutation is shown, which is caused by deletion of an exon that creates a frameshift (stop codon) in the downstream exon. Various strategies can be applied to correct loss-of-function mutations. Double-cut strategy will delete the out-of-frame exon to put exons back in frame. Single-cut strategy can promote exon skipping by targeting splice acceptor or donor sites and exon reframing. Knockin strategy relies on HDR DNA repair in the presence of a donor template. C, Base editing can correct single-nucleotide mutations (A to G and C to T) and promote exon skipping by mutating AG or GT at splice acceptor and donor sites, respectively. D, Prime editing can correct all possible single-nucleotide mutations and induce small deletions and insertions. WT indicates wild type. Credit: [Liu N. and Olson E. 2022].

Precision genome engineering for cancer immunotherapy - CRISPR in haemato-oncology

The influence of CRISPR/Cas9 technology in precision medicine has long-standing applications in the field of tumor immunotherapy [Feng X et al. 2024]. Immunotherapy targets the underlying, intricate nature of cancer biology to circumvent its progression at the molecular level. However, fundamental immune escape mechanisms inherent to cancer can alter the impact of therapeutic intervention [Riley R et al. 2019]. Bioengineers have already developed a variety of advanced biomaterials and drug delivery systems inclusive of nanoparticles with the use of T cells to deliver cancer immunotherapy [Riley R et al. 2019]. Newer efforts to optimize cancer immunotherapy have led to engineering next-generation CAR-T cells via CRISPR-Cas9 gene editing [Dimitri A. et al. 2022].

Despite its clinical efficacy, the optimal potential of CAR-T cell therapy for many solid cancers remains to be achieved. The factors underlying its dysfunction include T-cell exhaustion, lack of CAR-T cell persistence, and cytokine-related toxicities [Dimitri A. et al. 2022]. The ease and accessibility of CRISPR-Cas9-based gene editing can precision engineer CAR-T cells to install the desired genetic changes, with or without introducing a double strand break into the genome, for on-demand cancer immunotherapy. The existing scope to bioengineer next-generation CAR-T via synthetic tools and strategies, can target negative regulators of T-cell function by directing therapeutic transgenes to specific genomic loci for reproducible and safe CRISPR-based CAR-T cell products.

These strategies aim to ameliorate existing clinical issues and optimize cancer immunotherapy. In addition to building better CAR-T cells with CRISPR screening in multiple myeloma; a difficult to treat blood cancer [Knudsen N. et al. 2025]. The technology has shown the possibility of building a platform of responsible mutated genes in haemato-oncology, to better understand cancer cell survival, and proliferation in leukemia [Vuelta E. et al. 2021, Tzelepis K. et al. 2016].

Edits Made to Order – Treating rare hematological genetic disorders with CRISPR

Figure 13: How does prime editing work? Prime editing integrates nCas9 with reverse transcriptase and employs prime editing guide RNA (pegRNA) that contains a single guide RNA (sgRNA), a reverse transcriptase template (RTT) and a prime binding site (PBS). Prime editing allows the insertion, deletion, or replacement of short DNA sequences [Anzalone A et al. 2019, Joo J. et al. 2025]

Restoring functional red blood cells and hemostasis factors via CRISPR-Cas9 to treat sickle cell anemia, beta thalassemia, and hemophilia disorders is currently in the spotlight [Alayoubi A et al. 2023]. In hematological disorders, Physician-Scientists Haydar Frangoul, Stephen Grupp, and colleagues for the CLIMB SCD-121 Study Group have shown gene therapy with promising results via the FDA already approving CRISPR gene editing therapy (Casgevy) or Exagamglogene Autotemcel (Exa-cel). To treat transfusion-dependent beta thalassemia; a previously incurable rare blood disorder, and sickle cell disease, to deliver a major milestone in genetic medicine [Yen A. et al. 2024, Frangoul H. et al. 2024].

The technology modifies a patient’s own blood stem cells ex vivo to “switch-on” the production of healthy fetal hemoglobin to treat or eliminate painful transfusion needs by correcting the underlying genetic issue, that then prevents the sickling of red blood cells [Frangoul H. et al. 2024]. Geneticists and bioengineers who devised this strategy achieved low-risk, off-target editing during the process by selecting a unique on-target site or regulatory element such as BCL11A, with low sequence homology to the rest of the genome, with novel delivery strategies to enhance clinical translation [Yen A. et al. 2024, Liu H and Zhang P. 2025].

Base editing is yet another example of gene therapy mechanisms that incorporate Cas9 nickase, first reported by Biologist David Liu’s laboratory in 2016 [Joo J. et al. 2025]. Liu and team also introduced prime editing in 2019 as “edits made to order” for therapeutic intervention, in which Cas9 nickase integrates with reverse transcriptase and a prime editing guide RNA to insert, delete or replace short DNA sequences, in a mechanism now known as PERT (prime-editing mediated readthrough of premature termination codons), with the capacity to treat four different rare diseases in a single strategy (Figure 13) [Anzalone A et al. 2019].

Mechanistically, PERT aims to rescue a type of mutation known as “nonsense mutations” that cause about a third of rare genetic diseases, in order to treat multiple rare disorders via a single editing event, regardless of disease specifics. This highly resourceful method in genotherapy therefore targets genetic disorders caused by premature stop codons, by converting endogenous tRNA into an optimized suppressor tRNA (Sup-tRNA) to rescue the disease pathology (Figure 14) [Pierce S. et al. 2025]. When tested in human cell models of Batten disease, Tay-Sachs disease, and Niemann-Pick disease, and in a mouse model of Hurler syndrome, the PERT approach alleviated symptoms across all four of the diseases, and restored protein production, without off-target edits, changes in the normal RNA or protein production, or toxicity to the cells [Pierce S. et al. 2025], highlighting its remarkable viability in precision medicine.

Artificial Intelligence-based CRISPR in the Life Sciences lab

Artificial intelligence (when responsibly used) can support the advancement of CRISPR too. AI-based gene editing mechanisms typically employ AI algorithms to design new proteins and guide RNAs, while predicting off-target effects, in order to forecast gene editing outcomes ahead of the actual experiment [Joo J. et al. 2025]. In 2023, Systems Geneticist David Ichikawa and team developed a deep learning model for zinc finger design known as “ZFDesign,” in an effort for programmable regulation of gene expression, suited for any genomic target [Ichikawa D. et al. 2023]. The concept is based on a modern machine learning method that aims to overcome the design challenges that are inherent to the structurally intricate engagement of zinc finger domains with DNA.

CRISPR-based gene editing workflows can be further optimized with AI across multiple domains to predict off-target events, optimize guide RNAs (gRNAs) and simulate editing outcomes. Efforts for lab-to-clinic translation of CRISPR necessitate minimal off-target effects and the development of highly specific gRNAs to reduce unintended activity, predict prime editing and base editing outcomes in advance [Xiang X. et al. 2021, Marquart K. et al. 2021, Mathis N. et al. 2023].

Figure 15: Prediction of pegRNA editing rates by an attention-based bi-directional recurrent neural network. a) Illustration of the attention-based bidirectional recurrent neural network. Rectangles with circles represent vectors, b) Comparison of machine learning model performances on editing efficiency prediction, c) comparison of machine learning model performances on unintended editing rate prediction, d) evaluation of the PRIDICT-AttnBiRNN (attention-based bidirectional recurrent neural network) by comparing the measured editing efficiency of one cross-validation dataset with predicted efficiency, e) evaluation of the PRIDICT-AttnBiRNN model by comparing the measured unintended editing rate of one cross-validation dataset with predicted unintended editing efficiency [Mathis N. et al. 2023].

For example, prime editing requires experimental optimization of the prime-editing guide RNA (pegRNA) to achieve high editing efficiency, which can be achieved by using an attention-based bidirectional recurrent neural network known as PRIDICT (prime-editing guide prediction) trained on a database of sequence context-features. The PegRNAs with high vs. low PRIDICT scores substantially increased prime editing efficacy in diverse cell types in vitro and in hepatocytes in vivo, with potential for basic and translational research (Figure 15) [Mathis N. et al. 2023].

Geneticists and bioinformaticians can employ deep learning algorithms for AI to identify sequence patterns within previously conducted CRISPR experiments too, to precisely predict gRNA sequences with target specificity, and forecast the likely outcomes for gene editing to reduce experimental time and cost. The strategy further aims to optimize the CRISPR delivery options for improved efficacy of transfection, identify new therapeutic gene targets, and refine CRISPR-based gene therapy for safe gene editing in lab, for its clinical translation in precision medicine [Marino N. et al. 2020]. The AI-based algorithms can compare several gene editing tools to assess the best CRISPR system suited for experimental and clinical applications [Dixit S. et al. 2023, Joo J. et al. 2025].

Wrap up

As a gene editing technology, stemming from the many contemporary discoveries of Franscisco Mojica, Jennifer Doudna- Emmanual Charpentier, Feng Zhang, David Liu, Haydar Frangoul and team, among many others detailed here. CRISPR has set unprecedented scientific milestones with its technical dexterity across basic science and discovery research in the past few decades. The novelty of the method primarily stems from its efficient technological transferability from a prokaryotic defense mechanism to eukaryotic genome engineering [Alayoubi A et al. 2023]. Co-evolutionary arms races are fertile grounds for innovation as observed with the easily programmable specificity of the CRISPR-Cas nucleases, suited for applications across molecular biology, biotechnology, and medicine [Mathis N. et al. 2023].

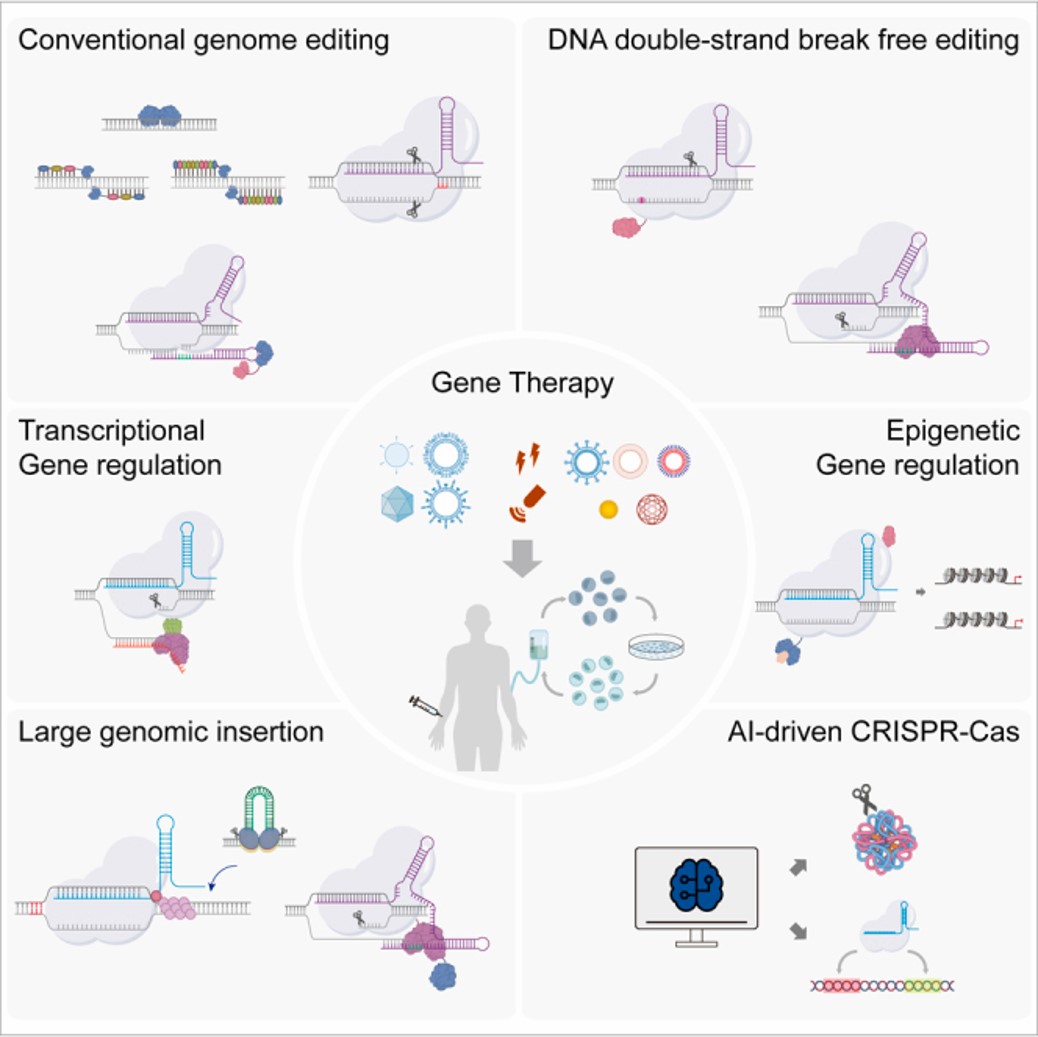

While the spectrum of CRISPR-associated gene editing mechanisms, gene knockouts, and gene regulation offer revolutionary advantages. The drawbacks include off-target effects, cellular toxicity, unexpected on-target effects, and immunogenicity that need to be addressed to develop safer genome editing applications. Geneticists, bioengineers and bioinformaticians have accomplished these goals through a collective arsenal of bona fide strategies to treat rare diseases, and to create AI-based algorithms to optimize these protocols, as detailed herein (Figure 16) [Chen B and Altman R. 2017, Joo J. et al. 2025].

Figure 16: A recap of the interdisciplinarity of CRISPR. The evolution of gene-editing technologies, with particular emphasis on the CRISPR-Cas system and its expanding applications from genetics and biotechnology to medicine [ Joo J. et al. 2025]

The interdisciplinarity of genome engineering shows the evolution of the multifunctional CRISPR platform with capacity for more precise modifications, with ongoing room for substantial improvement [Dominguez A. et al. 2016]. This is highlighted with emerging nuclease-based advanced CRISPR-derived platforms for base editing, prime editing, RNA editing and epigenome editing roles, alongside AI-based algorithms to optimize the technology [Ichikawa D. et al. 2023]. On a more interactive note, on the theme - the Howard Hughes Medical Institute (HHMI) has developed an interactive science website to help explore and learn more about the CRISPR-Cas9 biotechnology tool that is presently at the forefront of scientific research and gene editing.

The multifunctional interdisciplinary advances have scope to improve the precision, safety, and therapeutic potential of genome editing in mammalian cells, alongside its therapeutic delivery via CRISPR technology for genetics medicine or genotherapy, to treat rare genetic disorders, malignancies, and other complexities in the clinic, inclusive of treating hitherto “incurable” hematological disorders in humans.

Header Image - A still from the CRISPR-Cas9 biointeractive science website created via the Howard Hughes Medical Institute (HHMI).

References

- Doudna J. and Charpentier E. The new frontier of genome engineering with CRISPR-Cas9, Science, 2014

- Cong L. et al. Multiplex genome engineering using CRISPR/Cas systems, Science, 2013

- Xia C. et al. Single-molecule live-cell RNA imaging with CRISPR–Csm, Nature Biotechnology, 2025

- Alayoubi A et al. CRISPR-Cas9 system: a novel and promising era of genotherapy for beta-hemoglobinopathies, hematological malignancy, and hemophilia, Springer Nature, 2023

- Golkar Z. CRISPR: a journey of gene-editing based medicine, Genes and Genomics, 2020

- Davies K. and Mojica F. Crazy About CRISPR: An Interview with Francisco Mojica, Mary Ann Liebert, 2018

- Xu Y. and Li Z., CRISPR-Cas systems: Overview, innovations and applications in human disease research and gene therapy, Computational and Structural Biology, 2020

- You L. et al. Structure Studies of the CRISPR-Csm Complex Reveal Mechanism of Co-transcriptional Interference, Cell, 2019

- Zhang F. et al. Anti‐CRISPRs: The natural inhibitors for CRISPR‐Cas systems, Animals Models and Experimental Medicine, 2019

- Marino N. et al. Anti-CRISPR protein applications: natural brakes for CRISPR-Cas technologies, Nature Methods, 2020

- Ngo W. et al. Mechanism-guided engineering of a minimal biological particle for genome editing, Proceedings of the National Academy of Science of the United States of America, 2025

- Ishino Y. et al. Nucleotide sequence of the iap gene, responsible for alkaline phosphatase isozyme conversion in Escherichia coli, and identification of the gene product, Journal of Bacteriology, 1987

- Mojica F. et al. Intervening sequences of regularly spaced prokaryotic repeats derive from foreign genetic elements, Journal of Molecular Evolution, 2005

- Joo J. et al. Precision gene editing: The power of CRISPR-Cas in modern genetics, Molecular Therapy Nucleic Acids, 2025

- Barrangou R. et al. CRISPR provides acquired resistance against viruses in prokaryotes, Science, 2007

- Brouns S et al. Small CRISPR RNAs guide antiviral defense in prokaryotes, Science, 2008

- Gostimskaya I. CRISPR-Cas9: A History of Its Discovery and Ethical Considerations of Its Use in Genome Editing, Biochemistry, 2022

- Bolotin A. et al. Clustered regularly interspaced short palindrome repeats (CRISPRs) have spacers of extrachromosomal origin, Microbiology, 2005

- Binan L. et al. Simultaneous CRISPR screening and spatial transcriptomics reveal intracellular, intercellular, and functional transcriptional circuits, Cell, 2025

- Li T. et al. CRISPR/Cas9 therapeutics: progress and prospects, Signal Transduction and Targeted Therapy, 2023

- Jiang C. et al. Application of CRISPR/Cas9 gene editing technique in the study of cancer treatment, Clinical Genetics, 2020

- Heidenreich M. and Zhang F. Applications of CRISPR–Cas systems in neuroscience, Nature Reviews Neuroscience, 2015

- Jeewandara T. Biomaterials for Gene Editing – Facilitating CRISPR from the Lab to the Clinic, Springer Nature - Research Communities, 2023

- Bock C. et al. High-content CRISPR screening, Nature Reviews Methods Primers, 2022

- Chen S. et al. Genome-wide CRISPR screen in a mouse model of tumor growth and metastasis, Cell, 2015

- Kerek E. et al. Identification of Drug Resistance Genes Using a Pooled Lentiviral CRISPR/Cas9 Screening Approach, Methods in Molecular Biology, 2021

- Li B. et al. Genome-wide CRISPR screen identifies host dependency factors for influenza A virus infection, Nature Communications, 2020

- Dixit A. et al. Perturb-Seq: Dissecting Molecular Circuits with Scalable Single-Cell RNA Profiling of Pooled Genetic Screens, Cell, 2016

- Feldman D. et al. Pooled genetic perturbation screens with image-based phenotypes, Nature Protocol, 2022

- Quesnel-Vallieres M. et al. Autism spectrum disorder: insights into convergent mechanisms from transcriptomics, Nature Review Genetics 2019

- Wang Q. et al. Impaired calcium signaling in astrocytes modulates autism spectrum disorder-like behaviors in mice, Nature Communications, 2021

- Jaitin D. et al. Dissecting Immune Circuits by Linking CRISPR-Pooled Screens with Single-Cell RNA-Seq, Cell, 2016

- Elbashir S. et al. Duplexes of 21-nucleotide RNAs mediate RNA interference in cultured mammalian cells, Nature, 2001

- Hammel J. et al. Local gene knockdown in the brain using viral-mediated RNA interference, Nature Medicine, 2003

- Levanova A. and Poranen M. RNA Interference as a Prospective Tool for the Control of Human Viral Infections, Frontiers in Microbiology, 2018

- Smith R. et al. Antisense oligonucleotide therapy for neurodegenerative disease, Journal of Clinical Investigation, 2006,

- Kordasiewicz H. et al. Sustained therapeutic reversal of Huntington’s disease by transient repression of huntingtin synthesis, Neuron, 2012

- Gilbert L. et al. CRISPR-mediated modular RNA-guided regulation of transcription in eukaryotes, Cell, 2013

- Geurts A. et al. Knockout Rats Produced Using Designed Zinc Finger Nucleases, Science, 2010

- Plano L. et al. Applications of CRISPR-Cas9 in Alzheimer’s Disease and Related Disorders, MDPI, 2022

- Lewandoski M. Conditional control of gene expression in the mouse, Nature Review Genetics, 2001

- Doetschman T and Azhar M. Cardiac-specific inducible and conditional gene targeting in mice, Circulation Research, 2012

- Knott G. and Doudna J. CRISPR-Cas guides the future of genetic engineering, Science 2018

- Rouet P. et al. Introduction of double-strand breaks into the genome of mouse cells by expression of a rare-cutting endonuclease, Molecular and Cellular Biology,1994

- Liu N. and Olson E. CRISPR Modeling and Correction of Cardiovascular Disease, Circulation Research, 2022

- Anzalone A. et al. Genome editing with CRISPR-Cas nucleases, base editors, transposases and prime editors, Nature Biotechnology, 2020

- Feng X et al. CRISPR/Cas9 technology for advancements in cancer immunotherapy: from uncovering regulatory mechanisms to therapeutic applications, Experimental Hematology and Oncology, 2024

- Riley R et al. Delivery technologies for cancer immunotherapy, Nature Reviews Drug Discovery, 2019

- Dimitri A. et al. Engineering the next-generation of CAR T-cells with CRISPR-Cas9 gene editing, Molecular Cancer, 2022

- Knudsen N. et al. In vivo CRISPR screens identify modifiers of CAR T cell function in myeloma, Nature, 2025

- Vuelta E. et al. CRISPR-Cas9 Technology as a Tool to Target Gene Drivers in Cancer: Proof of Concept and New Opportunities to Treat Chronic Myeloid Leukemia, The CRISPR Journal, 2021

- Tzelepis K. et al. A CRISPR Dropout Screen Identifies Genetic Vulnerabilities and Therapeutic Targets in Acute Myeloid Leukemia, Cell Reports, 2016

- Yen A. et al. Specificity of CRISPR-Cas9 Editing in Exagamglogene Autotemcel, The New England Journal of Medicine, 2024

- Frangoul H. et al. Exagamglogene Autotemcel for Severe Sickle Cell Disease, New England Journal of Medicine, 2024

- Liu H and Zhang P. Advances in β-Thalassemia Gene Therapy: CRISPR/Cas Systems and Delivery Innovations, Cells, 2025

- Anzalone A et al. Search-and-replace genome editing without double-strand breaks or donor DNA, Nature, 2019

- Pierce S. et al. Prime editing-installed suppressor tRNAs for disease-agnostic genome editing, Nature, 2025

- Ichikawa D. et al. A universal deep-learning model for zinc finger design enables transcription factor reprogramming, Nature Biotechnology, 2023

- Xiang X. et al. Enhancing CRISPR-Cas9 gRNA efficiency prediction by data integration and deep learning, Nature Communications, 2021

- Marquart K. et al. Predicting base editing outcomes with an attention-based deep learning algorithm trained on high-throughput target library screens, Nature Communications, 2021

- Mathis N. et al. Predicting prime editing efficiency and product purity by deep learning, Nature Biotechnology, 2023

- Dixit S. et al. Advancing genome editing with artificial intelligence: opportunities, challenges, and future directions, Frontiers in Bioengineering and Biotechnology 2023

- Chen B and Altman R. Opportunities for developing therapies for rare genetic diseases: focus on gain-of-function and allostery, Orphanet Journal of Rare Diseases, 2017

- Dominguez A. et al. Beyond editing: repurposing CRISPR-Cas9 for precision genome regulation and interrogation, Nature Reviews Molecular Cell Biology, 2016

Please sign in or register for FREE

If you are a registered user on Research Communities by Springer Nature, please sign in