The oxytocin connection: new insights into cooperative relationships revealed by communally breeding house mice

Published in Ecology & Evolution and Neuroscience

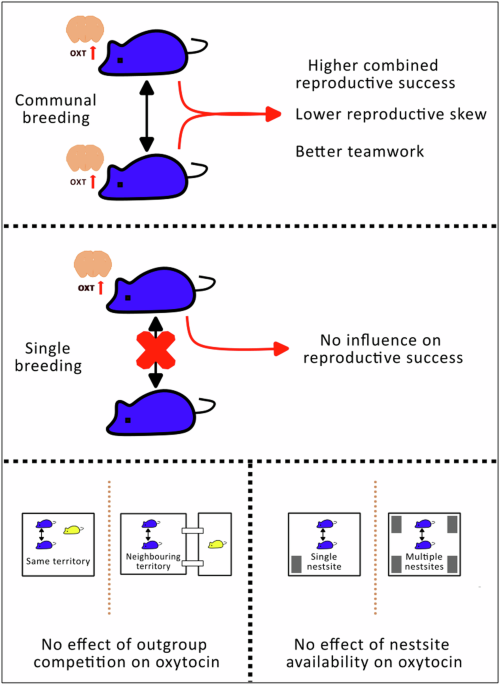

Female house mice show an interesting behaviour of often choosing to pool their litters into communal nests and cooperating to share offspring care. We found that cooperating sisters with higher oxytocin levels had more equal and greater combined reproductive success, as well as spending more equal time in the nest. By contrast, oxytocin levels were unrelated to reproductive success in the absence of cooperation, and did not vary in response to manipulation of social competition.

Cooperation and conflict in communally breeding house mice

We chose house mice as subjects for our study because of the tension between cooperation and conflict that arises when females raise their young communally. Cooperating involves a risk of exploitation, and females typically prefer close relatives as partners, which may help mitigate costs of being exploited 1,2. But even among related females, cooperative relationships can vary from relatively egalitarian to despotic, where one female gains fitness benefits at the expense of relatively greater investment by their partner 3,4. Oxytocin is often associated with social bonding 5, which could promote more equal investment in cooperation, so we wanted to test if natural variation in oxytocin levels of communally breeding sisters predicted the outcome of their cooperative relationships.

Our approach to quantifying oxytocin levels under naturalistic conditions

Because we were aiming to explore questions of evolutionary relevance, we felt that it was important to replicate the natural conditions experienced by wild house mice as closely as possible, while also carefully controlling their environment. The mice themselves were derived from wild populations and our experiments were run in indoor enclosures with subjects living in naturalistic social groups. By using an automated monitoring system, we were able to quantify the time spent in communal nests by cooperating females without disturbing them. The mice were allowed time for social groups to become established, for subjects to complete a reproductive cycle, and for a post-breeding recovery period. At the end of the study, we quantified oxytocin concentrations in the paraventricular nucleus of the hypothalamus, the main source of centrally-released oxytocin. Our focus was therefore on comparing variation in oxytocin production between subjects that had been living under relatively natural conditions over a prolonged period. This approach constrains the interpretation of our findings to some extent – i.e. we have not shown a direct causal link between oxytocin and behaviour, or quantified ‘peaks’ in oxytocin expression linked to specific social stimuli. But our approach also avoids some common difficulties of interpretation more typically associated with studies in natural populations, as these tend to rely on peripheral measures of oxytocin (e.g. in urine) which may be unrelated to central actions. Our study thus offers an advance by relating centrally measured oxytocin levels to variation in cooperative behaviour and reproductive success under naturalistic conditions.

Experiments of this nature are logistically demanding, not least because wild mice have not been selected for captive living and so are far more challenging to work with than their laboratory counterparts, requiring labour-intensive monitoring of social groups to ensure their wellbeing. The integrative nature of the study required a team with diverse expertise in wild mouse ecology, behavioural biology, evolution and neuroscience, while our desire to mimic naturalistic conditions depended on access to suitable facilities for this kind of complex work. We are hugely fortunate to have access to such custom-designed facilities within the Mammalian Behaviour and Evolution Group at the University of Liverpool, without which the study wouldn’t have been possible.

Exploring the role of social competition

One of the key motivations behind the study was our interest in social competition between females 6,7 and how this might influence cooperation. In contrast to studying competition between males, understanding female competitiveness has received much less attention. Previous studies of wild mammals suggest that competition with an ‘outgroup’ (e.g. a neighbouring social group) can promote closer within-group cooperation, and that oxytocin may be involved in mediating this response. We therefore tested if long-term exposure to competitors might lead to increased oxytocin production in female house mice. However, despite growing evidence linking oxytocin to outgroup responses 8, we found no evidence of plasticity in oxytocin production linked to outgroup competition.

Elevated oxytocin levels might also promote greater social tolerance within social groups under conditions where it is beneficial to share resources. For house mice, we hypothesised that this could apply where access to safe nest sites needed to reproduce is limited. Under such conditions, allowing a close relative to share a nest could ultimately be beneficial as otherwise they might fail to breed. We therefore manipulated access to safe nest sites for subjects in our study throughout a complete breeding cycle. However, we found no evidence of plasticity in oxytocin production in female house mice linked to nest site availability.

Why female social relationships matter

A further motivation for the study was to explore how relationships between adult females may ultimately influence social and mating systems. In egalitarian social systems, benefits of cooperation tend to be shared relatively evenly, whereas in despotic social systems, dominant individuals are more likely to benefit at the expense of others. Our study provides evidence of variation in the balance between egalitarian and despotic outcomes linked to central oxytocin levels of cooperating individuals. If similar variation is replicated across species, this could help us to understand the proximate factors influencing egalitarian and despotic social behaviours, hence providing broad insight into social system diversity. Our study thus offers potential new insights for understanding both the proximate basis of cooperative behaviour and the evolution of diverse social systems.

References

1 Green, J. P. et al. The genetic basis of kin recognition in a cooperatively breeding mammal. Curr. Biol. 25, 734; 10.1016/j.cub.2015.08.045 (2015).

2 Ferrari, M., Lindholm, A. K. & Konig, B. The risk of exploitation during communal nursing in house mice, Mus musculus domesticus. Anim. Behav. 110, 133-143 (2015).

3 König, B. Components of lifetime reproductive success in communally and solitarily nursing house mice - a laboratory study. Behav. Ecol. Sociobiol. 34, 275-283 (1994).

4 Green, J. P. et al. Cryptic kin discrimination during communal lactation in mice favours cooperation between relatives. Comm. Biol. 6, 734; 10.1038/s42003-023-05115-3 (2023).

5 Anacker, A. M. J. & Beery, A. K. Life in groups: the roles of oxytocin in mammalian sociality. Front. Behav. Neurosci. 7, 185; 10.3389/fnbeh.2013.00185 (2013).

6 Stockley, P. & Bro-Jorgensen, J. Female competition and its evolutionary consequences in mammals. Biol. Rev. 86, 341-366 (2011).

7 Fischer, S. et al. Fitness costs of female competition linked to resource defense and relatedness of competitors. Am. Nat. 201, 256-268 (2023).

8 Samuni, L. et al. Oxytocin reactivity during intergroup conflict in wild chimpanzees. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci USA 114, 268-273 (2017).

Photo credit: Mike Thom

Follow the Topic

-

Communications Biology

An open access journal from Nature Portfolio publishing high-quality research, reviews and commentary in all areas of the biological sciences, representing significant advances and bringing new biological insight to a specialized area of research.

Related Collections

With Collections, you can get published faster and increase your visibility.

Signalling Pathways of Innate Immunity

Publishing Model: Hybrid

Deadline: Feb 28, 2026

Forces in Cell Biology

Publishing Model: Open Access

Deadline: Apr 30, 2026

Please sign in or register for FREE

If you are a registered user on Research Communities by Springer Nature, please sign in