The pill that might be relieving your heartburn but killing your gut microbes

Published in Microbiology, Biomedical Research, and Pharmacy & Pharmacology

Who hasn´t turned to the conquests of the 21st century to alleviate that piercing pain in the chest, the aftermath of too much stress, caffeine, or alcohol? Proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) are increasingly (ab)used against heartburn, often with severe consequences such as intestinal infections with the bacterium Clostridioides difficile. These infections can manifest with varying symptoms, from mild (diarrhea and stomach pain) to very severe, leading to failure of multiple organs.

Previous studies have shown that continuous use of PPIs is accompanied by changes in the composition of the gut microbiome – the communities of bacteria, fungi, and viruses that colonize the human intestine. These communities regulate human metabolism, digestion, and the immune system, and protect the gut against invading pathogens like C. difficile. As a result, alterations in microbiome composition can increase the risk of developing, e.g., obesity, asthma, and diabetes, as well as the risk of infections. Whether PPIs directly harm some of our gut microbes has remained unclear. A study by scientists from the Cluster of Excellence “Controlling Microbes to fight Infections” at the University of Tuebingen, Germany, just published in Gut Microbes, shows that some gut bacteria are sensitive to prolonged pH changes triggered by PPIs rather than to PPIs themselves [1].

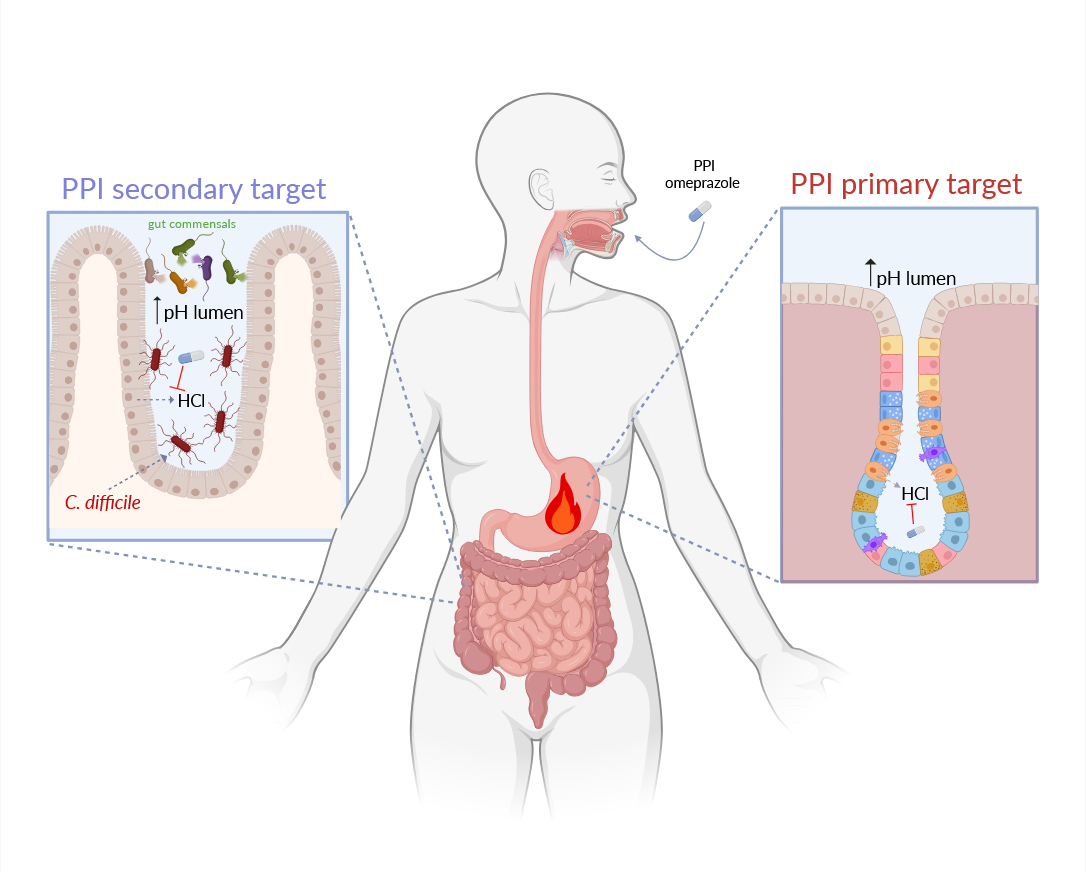

PPIs are among the most prescribed drugs worldwide: in the US alone, the PPI omeprazole was ranked the ninth best-selling drug in 2022 [2]. are generally indicated for treating infections with the bacterial pathogen Helicobacter pylori, gastroesophageal reflux disease, and gastric ulcers. However, since they are also available over the counter, in 50% of the cases, PPIs are used by people who don´t actually need them [3]. They inhibit a pump responsible for making the stomach acidic, thus increasing the stomach´s pH. A similar pump is present in the last part of the intestine, the colon, where microbial communities are the most abundant. Lead authors Lisa Maier and Bastian Molitor speculated that PPIs could change the pH of the colon, thus compromising the viability of some of the microbes therein. This, in turn, could promote C. difficile infections (CDI), which is (in)famous for promptly filling the gap left by beneficial gut microbes. This occurs, for example, after antibiotic treatment, which damages the gut microbiome and increases the risk of CDI.

Study´s first authors, Julia Schumacher and Patrick Mueller, tested this hypothesis by exposing selected gut microbes and C. difficile to omeprazole or extreme pH (5 or 9). The widely used PPI did not affect the growth of the tested gut bacteria or C. difficile. In contrast, extreme pH, particularly pH 5, inhibited the growth of most bacteria, including C. difficile.

Among other experiments, Julia and Patrick exposed a gut bacterial community derived from human stool samples to omeprazole or moderately altered pH (6 or 8) for 6 days. To do so, they cultured the bacterial community in so-called bioreactors, where microbes can be grown under controlled conditions, i.e., the levels of nutrients, drugs, pH, and temperature can continuously be monitored and adjusted to the desired level. Exposure to omeprazole at pH 7 (the average intestinal pH) did not alter the composition of the community, which retained the ability to inhibit the growth of C. difficile when the pathogen was added to the mixed culture. In contrast, exposure to pH 8 altered community composition to the point that the community was less effective in inhibiting the growth of C. difficile. This finding indicates that the damage to the microbes is caused by prolonged increases in pH rather than omeprazole (Figure 1).

Images created with Biorender.com

If you keep suffering from heartburn, turning to the magic pill might not always be the right solution: this could cause other health issues. Schumacher and colleagues show that prolonged increases in pH harm the beneficial microbes that inhabit our gut, decreasing their ability to protect us from bacterial pathogens. However, the use of PPIs is associated with additional side effects such as an increased risk of cancer. Could continuous exposure of gut microbes or human intestinal cells to increased pH be the underlying cause? We don´t know yet. One thing is for sure: consider changing your lifestyle rather than abusing PPIs. Your gut microbes will thank you!

References

- Schumacher, J., et al., Proton-pump inhibitors increase C. difficile infection risk by altering pH rather than by affecting the gut microbiome based on a bioreactor model. Gut Microbes, 2025. 17(1): p. 2519697.

- Shanika, L.G.T., et al., Proton pump inhibitor use: systematic review of global trends and practices. Eur J Clin Pharmacol, 2023. 79(9): p. 1159-1172.

- Savarino, V., et al., The appropriate use of proton pump inhibitors (PPIs): Need for a reappraisal. Eur J Intern Med, 2017. 37: p. 19-24.

Please sign in or register for FREE

If you are a registered user on Research Communities by Springer Nature, please sign in

Interesting facts and the problem statement to be addressed!