The power of air: Airborne environmental DNA plant community monitoring

Published in Ecology & Evolution

Lubbock, Texas is a challenging place to conduct traditional plant community surveys. It seems that just about every plant species you find is trying to stab you, while most of the animal life is trying to bite you. Honey mesquite (Prosopis glandulosa) for example, loves growing in dense patches in this environment while also sporting some rather impressive thorns. In addition to the biota making surveys challenging, the weather with >100 °F daytime high temperatures in the summer and haboob dust storms in the fall also offer unique challenges (Figure 1b). While these challenges may be specific to Lubbock, any location on Earth is going to offer unique challenges to field work and biodiversity monitoring. Despite these challenges, increasing rates of disturbance from climate change, biological invasion, and habitat destruction, make the monitoring of those ecosystems all the more important. However, traditional surveying, in addition to being physically challenging, oftentimes destroys the environment, takes long periods of time, and requires a lot expertise to accurately identify species. These challenges and shortcomings of traditional surveys matched with an urgency to conduct biodiversity monitoring indicates a need to explore other avenues of species detection. That’s why we have turned to the use of cutting edge genetic methods to address some of these concerns.

Figure 1. (A) Honey mesquite thorns (photo credit: Dr. Robert Cox) and (B) Haboob dust storm moving across Lubbock Texas (photo credit: Dr. Karin Ardon-Dryer)

Figure 1. (A) Honey mesquite thorns (photo credit: Dr. Robert Cox) and (B) Haboob dust storm moving across Lubbock Texas (photo credit: Dr. Karin Ardon-Dryer)

One of these genetic methods is environmental DNA (eDNA), which refers to the genetic material that is shed from an organism into its environment. Researchers can than collect bulk environmental samples such as water, soil, or air to determine whether that sample contains genetic material from a species of interest. Furthermore, this method has been shown to directly address the limitations of traditional surveys by being faster, more efficient, and less invasive. In our recently released manuscript we were interested in determining if airborne eDNA could be used to survey a whole plant community. Anyone who has suffered from allergies can attest to the fact that there is plant DNA in the air. While that means that there is pollen present, there is also DNA from a variety of other sources such as leaf fragments, flower fragments, and free floating DNA. Furthermore, we know that airborne eDNA is sensitive to the environment and can detect this varied material and acute changes on the landscape. This means that we can expand airborne eDNA analysis past pollen and single species detection to assess all the species on a study site regardless of how they pollinate (wind, insect, animal, etc.) or if they are currently pollinating.

To test this hypothesis, we preformed both a traditional and airborne eDNA plant community survey over the course of a year across the Texas Tech University Native Rangeland (Figure 2A). We revisited the thorns, heat, and snakes twice from June 2018 to June 2019 to conduct our traditional plant survey. The traditional surveys consisted of 9 sampling locations, each consisting of three 100 m transects organized as spokes around a central point. While this was taking place, we also deployed nine Big Spring Number Eight (BSNE) dust traps across the rangeland at the center of each one of our spokes (Figure 2a). Each BSNE trap consisted of two independent triangular metal collectors approximately 0.9 and 0.4 m above the ground (Figure 2b). Each collector included a metal sail that aligned the opening at the front of the collector into the wind to collect dust and particles at the bottom of the trap. The traditional surveys took hundreds of work-hours each to try and complete, with over ten volunteers and plant identification experts all working together to try and find the most diversity possible. On the other hand, the eDNA sampling events took only two hours to complete so we were able to sample eDNA 22 times across the entire year, taking fewer work-hours than a single traditional survey.

Figure 2 (A) The Texas Tech University Native Rangeland (Lubbock County, TX, United States) study site where both the traditional and metabarcoding plant community surveys were conducted. The points and numbers represent individual Big Spring Number Eight dust trap locations while the buffers around each point represent the 100 m traditional survey extent. (B) The Big Spring Number Eight Dust traps that collected the airborne eDNA.

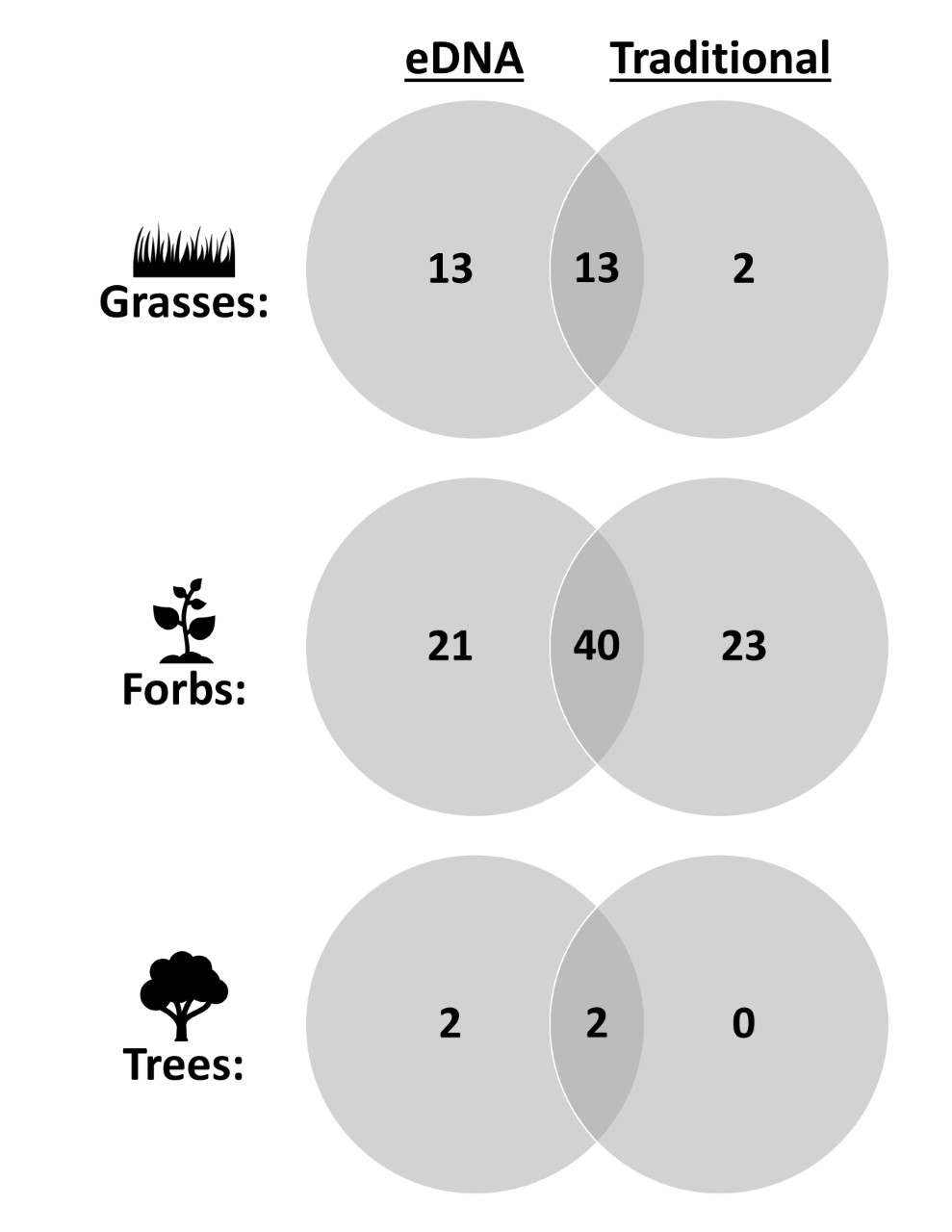

Upon examining our results, we found that our airborne eDNA survey was actually able to detect more species (N=91) compared to the traditional survey (N=80). In general, our airborne eDNA analysis detected more grasses and forbs with less showy flowers, while the traditional method detected fewer grasses but also detected rarer forbs with large showy flowers (Figure 3). Furthermore, the airborne eDNA survey was much more efficient than the traditional survey allowing us to survey across the entire year and see trends on our study site that the traditional surveys missed. For example, the eDNA survey found that tansy mustard (Descurainia pinnata) was one of the most common species on our study site, but interestingly, the traditional survey rarely found it. The reason for this we realized however, turned out to be a large bloom event that occurred between the two traditional surveys. For a month, our study site was dominated by this species, but by the time the traditional survey took place in May there was little remaining to indicate this. However, since our airborne eDNA methodology was so efficient we could sample more and were able to detect this explosion of tansy mustard. We also found that the eDNA survey detected more invasive species than the traditional survey. While both methods detected two invasive species, the eDNA survey was able to detect a third invasive, tree of heaven (Ailanthus altissima). This is exciting because tree of heaven represents an invasive species that is at the perfect stage for eradication. The most effective time to stop an invasive species is before it becomes established, and that is the stage tree of heaven is in at our study site, where airborne eDNA was the only method able to detect it.

Figure 3. Venn diagram displaying the number of (A) grasses, (B) forbs, (C) and trees that were found by the eDNA and traditional methods alone and together

Detecting and analyzing airborne eDNA has the potential to revolutionize the way plant communities are surveyed. Furthermore, we were able to detect various forms of species, regardless of pollination syndrome, indicating that airborne eDNA is not beholden to the presence of pollen or just wind pollinated species. With much less effort, we were able to detect more species than a traditional survey, including more invasive species. While more research is needed into the ecology of airborne eDNA (origin, state, transport, and state), airborne eDNA in general could help to detect invasive species, endangered species, track climate change, and monitor biodiversity. Thinking back to the challenges of monitoring the Lubbock plant communities (and other plant communities across the world), airborne eDNA could help to address these challenges while providing a plethora of information that could be used to better understand this changing world.

Follow the Topic

-

BMC Ecology and Evolution

An open access, peer-reviewed journal interested in all aspects of ecological and evolutionary biology.

Related Collections

With Collections, you can get published faster and increase your visibility.

Bioacoustics and soundscape ecology

BMC Ecology and Evolution welcomes submissions to its new Collection on Bioacoustics and soundscape ecology. By studying how animals use sound and how noise impacts them, you can learn a lot about the well-being of an ecosystem and the animals living there. In support of the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) 13: Climate action, 14: Life below water and 15: Life on land, the Collection will consider research on:

The use of sound for communication

The evolution of acoustic signals

The use of bioacoustics for taxonomy and systematics

The use of sound for biodiversity monitoring

The impacts of noise on animal development, behavior, sound production and reception

The effect of anthropogenic noise on the physiology, behavior and ecology of animals

Innovative technologies and methods to collect and analyze acoustic data to study animals and the health of ecosystems

Reviews and commentary articles are welcome following consultation with the Editor

(Jennifer.harman@springernature.com).

Publishing Model: Open Access

Deadline: Mar 27, 2026

Impact of climate change on ecology and evolution

BMC Ecology and Evolution is calling for submissions to our Collection on Impact of climate change on ecology and evolution. This Collection seeks to explore how climate change alters ecological dynamics and evolutionary processes, including shifts in phenology, local adaptations, and responses to invasive species. By understanding these shifts, we can gain insights into the resilience of ecosystems and the adaptive capacity of species in a rapidly changing world.

The significance of this research is underscored by the ongoing challenges posed by climate change, which threatens biodiversity and disrupts ecosystems. Recent advances in ecological modeling and genetic analyses have provided new tools to assess the impacts of environmental change on species and communities. These insights are crucial for developing conservation strategies and management practices aimed at mitigating the effects of climate change and preserving biodiversity for future generations.

Continued research in this area promises to enhance our understanding of the interplay between climate change and ecological dynamics. As new data emerges, we may uncover novel adaptive strategies employed by species in response to environmental shifts, revealing patterns of gene flow, population dispersal, and phenotypic plasticity. This knowledge can inform conservation strategies that are increasingly vital in an era of unprecedented environmental change.

•Climate change and biodiversity loss

•Phenotypic plasticity in response to environmental change

•Effects of invasive species on ecosystems

•Local adaptation and genetic structure in changing environments

This Collection supports and amplifies research related to SDG 13: Climate Action and SDG 15: Life on Land.

Publishing Model: Open Access

Deadline: Mar 03, 2026

Please sign in or register for FREE

If you are a registered user on Research Communities by Springer Nature, please sign in