The Puzzling Mpemba Effect: When should a hotter fluid solidify quicker than a colder one?

Take two samples of liquid water at two different temperatures. Put them inside a refrigerator working at a subfreezing temperature. Which of the two will transform into ice more quickly than the other? The likely answer from those to whom the question appears trivial is the “colder” of the two, possibly because the latter is thermodynamically closer to the destination state. However, the question is far from trivial. Hotter water can freeze faster than colder water! The quest for an explanation of this counterintuitive observation dates back to the time of Aristotle. There have been efforts to interpret it via Newton's law of cooling, transport phenomena in general, and other rational approaches. However, a complete explanation remains largely elusive. Even a computer simulation demonstrating the effect is nonexistent, owing to the complex nature of water molecules and the interactions among them.

Interestingly, this surprising fact of science, involving such commonly used matter, is unknown to most. I first heard about it from Michael Fisher. After my postdoctoral research at the University of Maryland, when I was leaving for India with a permanent job in 2007, he tried to make me curious about it. Since water is a complex system, and I had no prior exposure, I had at that time thought of investigating whether a similar effect can be observed in simpler situations, say, during magnetic transitions in the Ising model. However, I forgot about this desire—just as the puzzling effect itself, since the days of Aristotle, had been forgotten, possibly many times, only to be rediscovered later. The most recent rediscovery was made by Erasto Mpemba, accidentally, when he was a school student in Tanzania, after whom it is now named.

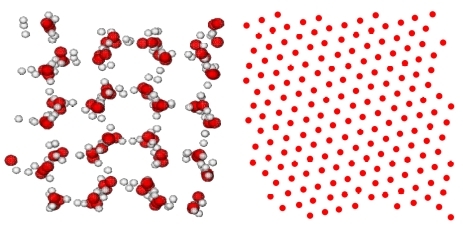

My serious effort, with the Ising model, started with a graduate student, Nalina Vadakkayil, in 2020. By then, the effect had been identified in a few more systems, with a general perception that metastability is a requirement for the exhibition of the effect. Since we were working with the pure Ising model, without any element of in-built disorder or frustration, we received discouragement from certain quarters—of course, for valid reasons. Despite the criticism, we moved ahead and made a new observation, albeit for a theoretical model system: the effect can be seen even in the absence of metastability! In the meantime, I was able to generate interest in water in another graduate student, Soumik Ghosh. He started simulations with the TIP4P/Ice model.

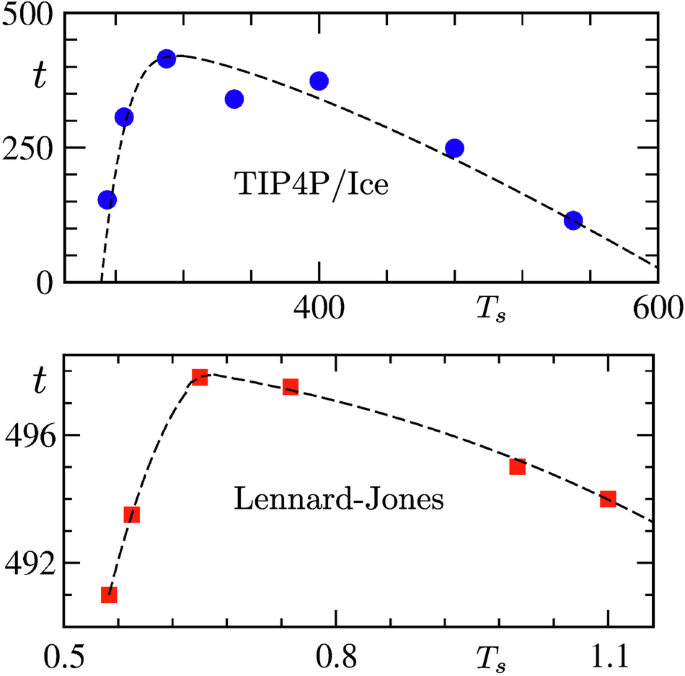

For water, we immediately realized that it would be impossible to arrive at a conclusion if we studied systems of sizes that are typically considered in present-day literature. However, small need not be bad. Therefore, we considered systems of rather tiny size to be able to simulate for longer, which also was necessary. Choices of ensemble was a matter of concern as well. However, much experimentation was not practical due to the limited availability of resources. We stuck to the isothermal-isobaric case, with about a hundred molecules. Objective was to gather a picture quick enough, using some framework, even if it is not the best, because there exist views even against the very existence of the effect. Our strategy paid off by producing a feature that is qualitatively quite similar to that described in the original article of E. Mpemba and D. Osborne. This, we believe, tells a positive story. Around this time, Purnendu Pathak, another graduate student, became engaged in investigating whether this is specific to water or simpler systems like Lennard–Jones models are also good candidates for exhibiting the effect during fluid–solid transitions. The outcomes of the simulations in the latter case also appeared positive. Thus, Mpemba effect is reasonably common, given that several other experimental and theoretical models have also been shown to exhibit it. Explanations in each case can potentially lead to significant improvement in our understanding of nonequilibrium phenomena and provide grounds for practical applications.

That hotter samples equilibrate faster at a lower temperature implies, in a thermodynamic sense, faster arrival from the more distant state. This can be related to the suitability of available paths, better or worse, from different starting points to the destination. Computer simulations can be appropriately explored to record trajectories and understand how paths, thus the transport properties, are modified by changes in the initial state. To verify the concept of faster arrival from the more distant state, tuning parameters other than temperature can also be chosen.

For water, consideration of a small system essentially allows us to probe the nucleation part. It is interesting to note that only the delay in nucleation, in our study, due to initial temperature-dependent metastability, provides not only a Mpemba-like effect but also captures the overall experimental feature! Although this is an important finding, to reproduce the effect at experimentally observed length and time scales, a study of kinetics with systems of much larger sizes will be necessary, preferably also in the canonical ensemble, combined with scaling analysis. While this is a difficult task for water, we have carried out a large-scale study of kinetics in the case of Lennard–Jones systems. It should be noted that for the latter case, metastability is not the reason behind the effect. Here, as opposed to the case of water, initial configurations differ significantly from each other in terms of spatial correlations, which extend over extremely long ranges as the initial state approaches the critical point of the second-order phase transition. This is similar to the magnetic case that Sohini Chatterjee, another graduate student, built upon, following the first work on the Ising model, along with Nalina and two postdoctoral fellows, Tanay Paul and Sanat Singha. Thus, the work, combined with the others, identifies two different classes of systems in terms of the reasons leading to the Mpemba effect.

In the case of the critical fluctuation category, further studies should be carried out to separate the time, from the overall duration, spent by systems in destroying the initial spatial correlations that may result in delays in arriving at the new state. For water, the original experiments were for liquid-to-solid transitions. However, we have explored both liquid and vapor regions for the preparation of initial states. Realization of the effect by keeping the initial temperatures confined only within the liquid region of the phase diagram is difficult due to the lack of a large window of temperature, noting that obtaining much superior statistics then becomes a necessity. However, given that even with a significantly large time window most simulation runs do not end up in frozen states, acquiring accurate data for average freezing time is a tough task. Consideration of larger systems should facilitate a higher probability of ice nucleation. It is thus left to better resources, the availability of which will also provide more stability to the ice phase and opportunities to study post-nucleation kinetics.

Follow the Topic

-

Communications Physics

An open access journal from Nature Portfolio publishing high-quality research, reviews and commentary in all areas of the physical sciences.

Related Collections

With Collections, you can get published faster and increase your visibility.

Higher-order interaction networks 2024

Publishing Model: Open Access

Deadline: Feb 28, 2026

Physics-Informed Machine Learning

Publishing Model: Hybrid

Deadline: May 31, 2026

Please sign in or register for FREE

If you are a registered user on Research Communities by Springer Nature, please sign in

I have published a theory of the Mpemba Effect (Am. J. Phys. 77, 27 [2009]) that predicts that it occurs in hard water but not in soft water; the solutes are essential. It does not seem to have been tested---published experiments have not characterized their water.