CMV: A Hidden Influencer of Mental Health?

Published in Healthcare & Nursing, Microbiology, and Anatomy & Physiology

As a researcher engrossed in exploring the brain changes associated with mood disorders, I've found myself immersed in the mystery of what could be triggering these changes. In a surprising twist, our research team has identified a new player that could significantly impact our mental well-being more than we ever anticipated: Human Cytomegalovirus (CMV). CMV is a member of the herpesvirus family and can infect the brain when the anti-viral control is compromised. Most humans are exposed to CMV at some point in their lives, where it then remains dormant in the body. Our new research suggests that this latent infection may be linked to mood disorders, suicide, and neuroinflammation, possibly acting as a hidden influencer in our brain and mental health [1].

Unraveling the Enigma of CMV

At first glance, CMV might seem an unlikely suspect in psychiatric conditions. It is typically harmless in healthy individuals, with many unaware they even carry it. However, CMV has sparked our team’s research interest due to its association with multiple psychiatric disorders like mood disorders and schizophrenia. This virus quietly establishes lifelong latent infections, with occasional reactivations by psychological stress or inflammation. But it can cause harm to those people who are immunocompromised. A significant part of the intrigue comes from the fact that both stress and inflammation are common triggers for psychiatric conditions. However, CMV can also worsen inflammation, which hints at a dangerous cycle that could potentially fuel the development of mental illnesses. Most of our understanding of CMV's relationship with psychiatric disorders comes from epidemiological studies [2]. Researchers have found higher rates of CMV in depressed individuals and have even linked CMV infection to an increased risk of depression [3, 4] and non-affective psychosis [5].

Navigating Through The Twists and Turns of CMV Research

Over the past few years, my colleagues and I have been investigating the connection between CMV infection and major depressive disorder (MDD). We made some promising discoveries using neuroimaging techniques. Our data suggest that those with MDD who also tested positive for CMV tend to exhibit neuroimaging abnormalities, such as reduced gray matter volume [6, 7], lower white matter integrity [8], and decreased functional connectivity within neural networks [7] that are important for emotion regulation. However, one question lingers: does CMV cause these abnormalities, or is it merely associated with them? We examined post-mortem samples to probe further, hypothesizing that CMV seropositivity and higher antibody levels could be linked to increased odds of psychiatric disorders, suicide, and neuroinflammation.

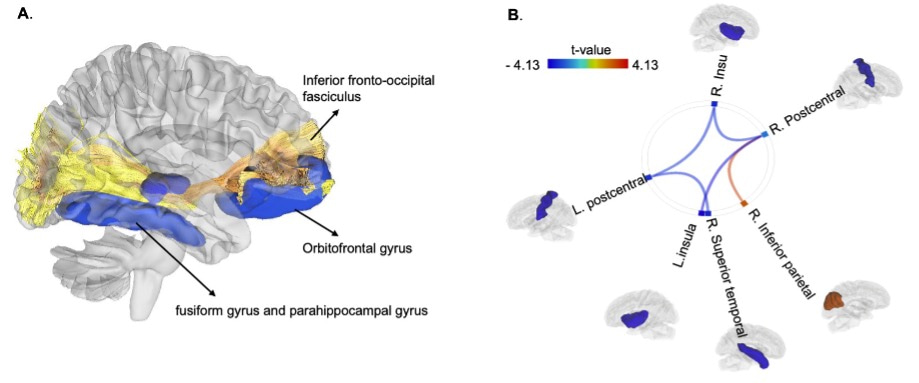

Figure 1. CMV seropositivity is associated with structural and functional brain alterations in depression. In our previous study, we found that relative to CMV negative (CMV-) depressed participants, matched CMV+ participants showed (1) reduced temporal lobe white matter integrity (fractional anisotropy, FA) of the inferior fronto-occipital fasciculus, a major tract connecting the orbitofrontal cortex and the occipital cortex via the temporal lobe [8] (see Figure 1. A), (2) reduced gray matter volume in the frontotemporal regions (i.e., orbitofrontal cortex, fusiform gyrus, and parahippocampal gyrus) [6, 7] (see Figure 1. A), and (3) reduced functional connectivity between the salience network and sensorimotor network [7] (see Figure 1. B).

The Intriguing Findings: CMV, Psychiatric Disorders, and Neuroinflammation

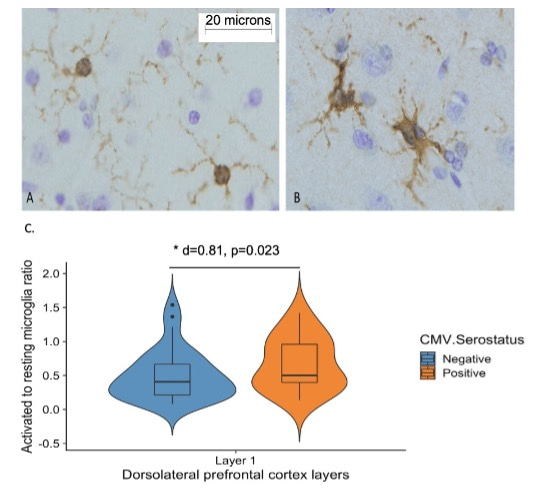

Our findings indicated that CMV seropositivity was more common in individuals with psychiatric disorders than in controls. Furthermore, CMV seropositive individuals were more likely to have a mood disorder and were also more likely to die by suicide. Although we didn’t find a statistically significant relationship between CMV serostatus and inflammation-related gene expression levels, the odds of having high inflammation-related gene expression were more than 4 times higher in individuals with elevated anti-CMV antibody levels. Interestingly, CMV seropositivity was also linked with increased microglia activation, suggesting a higher level of neuroinflammation [1].

Figure 2. Associations between CMV infection and microglia activation. A, Ramified (resting) microglia displayed small, round cell bodies with numerous thin, branched processes, whereas B, non-ramified (activated) microglia displayed enlarged or amorphous soma, and processes that were thickened, fewer in number or absent. C, CMV seropositivity is associated with an increased ratio of non-ramified to ramified microglia.

Our research, in alignment with existing literature, suggests a potential pathway where CMV-related neuroinflammation could lead to psychiatric disorders. Stress weakens our antiviral immunity and heightens the inflammatory response, leading to increased CMV reactivation and a heightened immune response to viral infection. Simultaneously, CMV can directly induce neuroinflammation by infecting endothelial cells (those forming the blood-brain barrier) and other brain cells. This could result in a continuous cycle of unresolved neuroinflammation in the central nervous system, leading to structural and functional changes in the brain critical to mental health.

A New Road to Explore in Psychiatry?

These findings not only illuminate a potentially concealed risk factor for mood disorders and suicide - CMV infection, but they also shed new light on the intricate link between physical health (specifically, the immune system) and mental health. This insight can guide us toward a more comprehensive understanding of holistic well-being. While there is still much to uncover about CMV’s precise role in these disorders, these initial findings suggest that its influence on neuroinflammation may be a significant piece of the puzzle. If further research confirms CMV's role, it might open up new avenues for mitigating neuroinflammation and treating mental illness, given that there are already approved medications for CMV.

As a researcher, we always hope that our work will help to inform treatments and improve patient outcomes. While the mystery of CMV is only a fragment of the larger picture, every piece brings us a step closer to understanding mental illness. We'll keep looking, keep testing, and keep hoping – because the journey to understand mental illness is far from over, and the answers might lurk in the most unanticipated corners.

Reference:

- Zheng, H., et al., Cytomegalovirus antibodies are associated with mood disorders, suicide, markers of neuroinflammation, and microglia activation in postmortem brain samples. 2023.

- Zheng, H. and J. Savitz, Effect of Cytomegalovirus Infection on the Central Nervous System: Implications for Psychiatric Disorders. Curr Top Behav Neurosci, 2022.

- Simanek, A.M., et al., A Longitudinal Study of the Association Between Persistent Pathogens and Incident Depression Among Older U.S. Latinos. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci, 2019. 74(5): p. 634-641.

- Burgdorf, K.S., et al., Large-scale study of Toxoplasma and Cytomegalovirus shows an association between infection and serious psychiatric disorders. Brain Behav Immun, 2019. 79: p. 152-158.

- Dalman, C., et al., Infections in the CNS during childhood and the risk of subsequent psychotic illness: a cohort study of more than one million Swedish subjects. Am J Psychiatry, 2008. 165(1): p. 59-65.

- Zheng, H., et al., A hidden menace? Cytomegalovirus infection is associated with reduced cortical gray matter volume in major depressive disorder. Mol Psychiatry, 2020. i.

- Zheng, H., et al., Association between cytomegalovirus infection, reduced gray matter volume, and resting-state functional hypoconnectivity in major depressive disorder: a replication and extension.Transl Psychiatry, 2021. 11(1): p. 464.

- Zheng, H., et al., Replicable association between human cytomegalovirus infection and reduced white matter fractional anisotropy in major depressive disorder. Neuropsychopharmacology, 2021. 46(5): p. 928-938.

Follow the Topic

-

Molecular Psychiatry

This journal publishes work aimed at elucidating biological mechanisms underlying psychiatric disorders and their treatment, with emphasis on studies at the interface of pre-clinical and clinical research.

Please sign in or register for FREE

If you are a registered user on Research Communities by Springer Nature, please sign in