The Twelfth Labour of Scientists: The Peer Review process

Published in Ecology & Evolution

The title is puzzling. Intentionally. Most of us – including myself – are not really familiar with mythology and stories involving Gods, demons, and dogs (?!). But surprisingly, mythology bears remarkable similarity to the structure of the academic Peer Review process.

Heracles (aka ‘Hercules’) – the son of Zeus and Alcmene – is considered the greatest of the Greek heroes, even though he killed his wife and children. The story goes that after this ‘little incident’, Heracles prayed for guidance to Apollo and was told to serve Eurystheus, the king of Mycenae, for 12 years. Eurystheus did not hold back. He gave Heracles 12 ‘jobs’ (labours) to be completed, the last of which was nothing less than to capture the three-headed dog Cerberus which guarded the gates of hell (Fig 1). Eurystheus was cheeky – he gave Heracles this task because he thought it was impossible. After all, Cerberus had three heads, snakes popping out all over his body, was the guardian of hell’s gates and was quite acquainted with Hades, the king of the underworld.

The story about how Heracles captured Cerberus is inconsistent. Some say that he had to fight Hades for Cerberus. Others say that he asked Hades for the dog (How would that go anyways: ‘Yo Hades, can I take y’ dog for a walk?’). The important point here is that Heracles managed to accomplish this impossible mission. He tamed Cerberus.

Now what on Zeus’ name does this have to do with Peer Review?

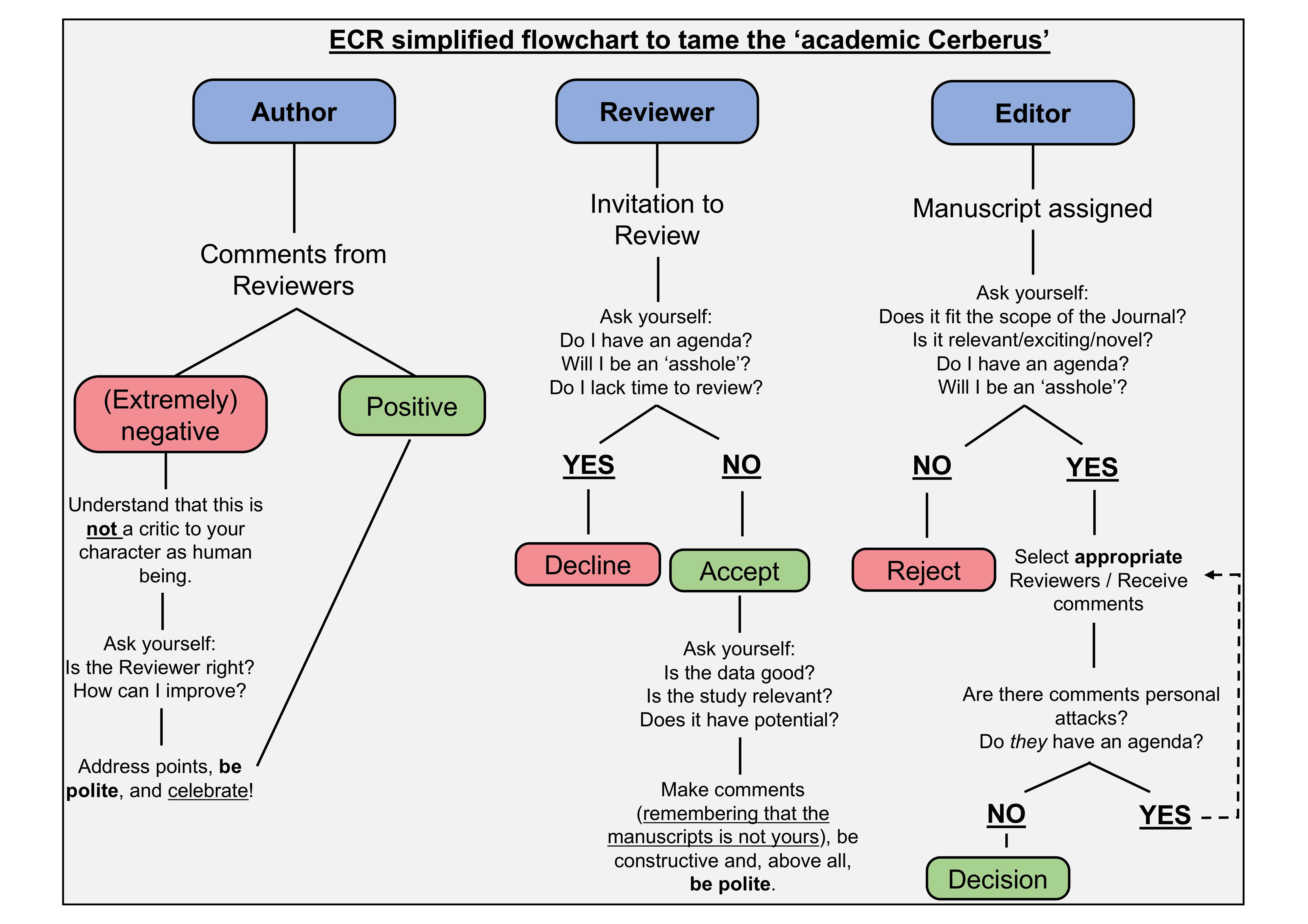

Well, as an Early Career Researcher I often found myself in Heracles’ position – having to balance out and manage to tame ‘three heads’: being an author, a reviewer, and an editor. It isn’t always easy – and in fact, all roles have their challenging moments. My aim with this post is to be honest about how I felt in my first time playing each one of these roles and how – to this date – I have managed to tame the academic Cerberus behind the Peer Review process. I also provide a very simple flowchart to how I try to keep everything under balance on a daily basis.

Head 1: Author. Having comments back from Reviewers and/or decision letters from Editors can be really disheartening. This is particularly true when we unfortunately fall on the hands of reviewers and editors with an agenda. And I wish I could say that this is rare – but it is not. The truth is some reviewers do not want you (or your supervisor) to publish a paper, no matter how good the paper is.

As an author, I have experienced the best and the worst in reviewers. I had comments that were as positive as if they had been written by a family member, with compliments such as ‘this is the closest I have ever been to recommend acceptance without revisions’. On the other hand, I have had some nasty ones, claiming that my work is ‘worse than an undergraduate project student and should never be published anywhere’. As an author (and ECR) is important to have in mind that the truth likely lies somewhere in between. Your study is unlikely to be as ground-breaking as you may think it is, but it is also far from being the worse piece of science that ever came to light in human history. It is hard to tame this head of the Cerberus but it is the head that we, as scientists, depend on to thrive in our careers.

Head 2: Reviewer. After taming head one and publishing few papers, we are likely to be invited to review someone else’s work. The pressure is on – you feel like you have the power to decide whether or not someone will live or die (metaphorically speaking, of course). In my opinion, this power corrupts some reviewers, and they use this opportunity in conjunction with anonymity of the Peer Review process to distilled their bitterness into other peoples’ work. The result we know all too well (see point above if unsure). However, others truly step up for the challenge and are very good reviewers, with thoughtful and insightful comments and fair recommendations. Note that I am not implying good reviewers are always bubbly and recommend acceptance. A good reviewer makes a fair point – either for revisions or for rejection.

I strive for the latter but sometimes it can be difficult. One caveat I notice is that we (ECRs) tend to over-analyse the manuscript we are reviewing, and highlight every possible thing we think is wrong with it.

We must resist this temptation.

After all, the manuscripts we review are not our own. We should provide useful feedback of course, and improve the manuscript when possible. But it is not our job as reviewers to re-write and/or re-analyse every aspect of the manuscript. Our job as reviewers is to assess the quality of the data and the manuscript, its relevance and implications to the field. While suggesting corrections is part of our role as reviewer, we should not attempt to make the authors change everything for our own sake.

Head 3: Editor. Now things get real. As an editor, we are the contact point between the authors (head one) and the reviewers (head two). We are responsible for assessing the potential relevance of the manuscript, find suitable reviewers, review the manuscript ourselves and more painfully, have the final decision on the fate of someone else’s study.

As an ECR I felt quite overwhelmed the first time I played a role as an Editor. Authors do not, and will not, make life easier as well. Recently, I have had a very aggressive group of authors displaying their arrogance in an attempt to justify why they thought their work was the best in the galaxy and therefore did not need any revisions. I do my best to keep things professional though, and I overlook arrogant comments. I also see through bad figures and incorrect English because after all, not all of us write perfect English (yes, this applies to me as well, I know!). As an editor, I try to see the value and quality of the data and if needed, with the help of the reviewers, guide the authors in shaping the manuscript the best way possible. Rejections are inevitable. But as editors, I believe we can play a key role in harmonising authors and reviewers thereby improving manuscript quality and benefiting Science more broadly.

With that, I would like to finish off by acknowledging that the Peer Review process is the most powerful tool we have to guarantee the highest scientific standards. Having said that, I would like to encourage you to write your experiences as an Author, Reviewer, and/or Editor. You may agree or disagree with my opinions, that’s fine. My aim here is for us to know: how do you – like Heracles – manage to tame these three heads of the academic Cerberus?

Please sign in or register for FREE

If you are a registered user on Research Communities by Springer Nature, please sign in

I love this - the three Heads of Peer Review, brilliant! Which head came first - author?

Thank you Ruth!

Definitely author comes first – that's how we get to be known and invited to be Reviewers (Head 2) and Editors (Head 3) =)

Why don't we hear from your experience as part of this community?

A couple for things spring to mind. During my time in research and publishing (more than 10 but less than 15 years), I have never heard of a manuscript being accepted without any revisions at all - even the *best* (whatever that means) can always be improved. And I know too well how hard it can be sometimes finding suitable referees for a paper - a couple of papers I've looked after have definitely topped 50 before!