Was Elon Right About Cognitive Biases?

Published in Behavioural Sciences & Psychology, Education, and Economics

Back in simpler times, Elon Musk tweeted this:

We looked at that tweet and thought: "Huh. Should it, though? And more importantly—can it?"

Now, we're not saying Musk needs a refresher course himself, but let’s just say his last year might be a "collection of interesting decision-making case studies."

Still, Musk's original tweet raised a genuinely important question. Both of us have found understanding cognitive biases transformative for our own careers. Learning about the sunk-cost fallacy helped us finally leave projects that weren't working. Understanding confirmation bias made us both better researchers—forcing us to actively seek evidence that might prove us wrong. And recognising scope neglect and the availability heuristic helped us make career decisions based on data rather than following the steps of that one person who "made it big." But, these are just anecdotes, not randomised experiments.

So, we did what researchers do: spend 3 years finding all the randomised trials that tested whether Musk's proposal actually works. Can you teach young people about cognitive biases in a way that sticks? Does knowing about these mental traps actually help people avoid them? Or is it like knowing that optical illusions are illusions—your brain still gets tricked anyway?

Bias Researchers Succumb to the Planning Fallacy too

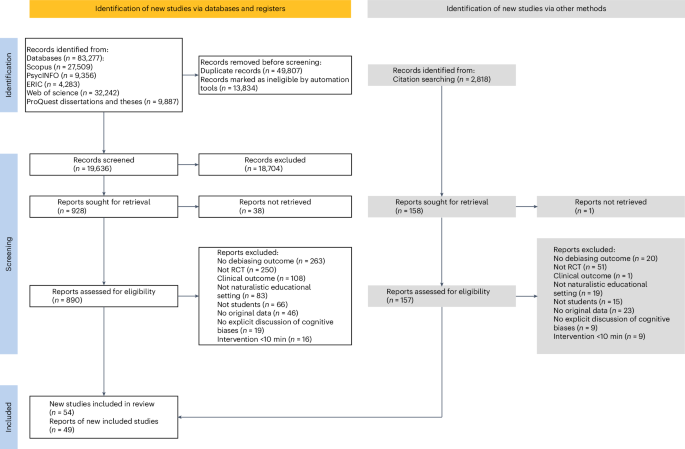

What followed was an exhaustive search through the academic literature. We screened 19,636 abstracts to respond to a 280-character tweet. In academia, we call this a 'proportional response.' But, once we were in, we weren’t going to quit (even if we should have). We read over 1,000 full papers, and ultimately analysed 54 randomised experiments involving almost 11,000 students.

The results? A resounding "yes, but..."

Yes, you can teach students about cognitive biases. Yes, it can help them make better decisions. But, it's much harder than just showing them a colourful infographic of "50 biases to avoid."

What Actually Works (And What Doesn't)

A few things surprised us: confirmation bias, arguably the most famous thinking trap, proved almost impossible to budge through education. We can teach people about it, they can understand it intellectually, but when push comes to shove, they still seek information that confirms what they already believe. Ironically, we still think this must be possible to change—we’re just less confident we know how.

Some approaches showed real promise. Educational games outperformed lectures. Teaching multiple biases together worked better than targeting them individually. And overconfidence—like where 90%+ of us academics think we’re above average teachers—actually responded well to training with good feedback.

The key seemed to be direct experience plus immediate feedback. Students needed to make decisions, see their biases in action, and immediately understand where they went wrong. Lectures about biases were like lectures about swimming without ever getting in the pool.

From Research to Real Impact

What excites us most is where this research is heading. We’re now using these insights to help high school students make better career decisions—arguably one of the most important and bias-prone choices young people face. The best way to teach cognitive biases requires immediate feedback. Unfortunately, life gives you feedback about your career choices roughly 20 years too late. In an era where AI is reshaping the job market faster than anyone can predict, helping students think clearly about their futures isn't just nice to have. It's essential.

We're talking about decisions that determine life satisfaction, financial security, and personal fulfilment. Yet, most career education still relies on outdated models like "follow your passion" or "what colour is your parachute?" Meanwhile, students are anchoring on the first career they are interested in, falling for survivorship bias when they see successful influencers, and letting status quo bias keep them doing things that no longer serve them. As a bonus, we think good decision-making can help the next generation to be more ambitious and solve the world’s problems.

The Ironic Truth About Teaching Clear Thinking

Perhaps the most humbling finding from our review was that even when interventions worked, the effects were modest. We can't just download better thinking like a software update. The human brain, it turns out, comes with its biases as standard features, not bugs. But that's exactly why this work matters. If changing how we think is this hard, we need to change our curricula to get there.

So was Elon Musk wrong? Not exactly. Teaching young people to reduce their cognitive biases is a worthy goal. But it takes more than a clever infographic. It takes carefully designed educational experiences, lots of practice, and immediate feedback. It's hard work, but given the quality of decisions we're seeing in the world today—from boardrooms to ballot boxes—it might be some of the most important work in education.

After all, if a tweet about cognitive biases can inspire a three-year research project involving 20,000 abstracts, we've either proven the importance of rational thinking or demonstrated our own spectacular vulnerability to the sunk cost fallacy. We'll let you decide which.

Follow the Topic

-

Nature Human Behaviour

Drawing from a broad spectrum of social, biological, health, and physical science disciplines, this journal publishes research of outstanding significance into any aspect of individual or collective human behaviour.

Please sign in or register for FREE

If you are a registered user on Research Communities by Springer Nature, please sign in