Three mechanisms of language comprehension are revealed through analysis of individuals with language deficits

Published in Social Sciences, Ecology & Evolution, and Neuroscience

The evolution of humans saw the emergence of a biological system of language with two key components: articulate speech and the capacity for language comprehension. As demonstrated by our research and that of others, these components can develop independently: many nonverbal individuals possess full language comprehension abilities, and many verbal individuals exhibit minimal language comprehension.

Non-human primates are unable to acquire articulate speech, and for millennia, speech has been considered the sole uniquely human component of language. Charles Darwin viewed the evolution of articulate speech as the central factor in humanity's acquisition of language. In 1871, Darwin wrote:

I cannot doubt that language owes its origin to the imitation and modification, aided by signs and gestures, of various natural sounds, the voices of other animals, and man’s own instinctive cries.

In his view, Darwin followed Max Müller (1861) who assumed that once hominins had stumbled upon the appropriate mechanism for producing articulate speech, a communication system would develop, and language would evolve.

Noam Chomsky was the first to scientifically articulate the uniqueness of the human language comprehension component, defining it as “recursive mental operations,” “the faculty of language in the narrow sense,” and the “Merge operation.” Much like the mythological Prometheus, who bestowed upon humans fire, knowledge, and the gift of foresight, Chomsky envisions Prometheus as the first human to acquire recursive language around 100,000 years ago. This event, according to Chomsky, marked the separation of modern humans from their non-recursive ancestors, who, like Prometheus' brother Epimetheus, were limited to hindsight alone. Chomsky’s hypothesis, however, is rooted in linguistic theory, without offering a neuroscientific model.

Empirical evidence for three mechanisms of language comprehension

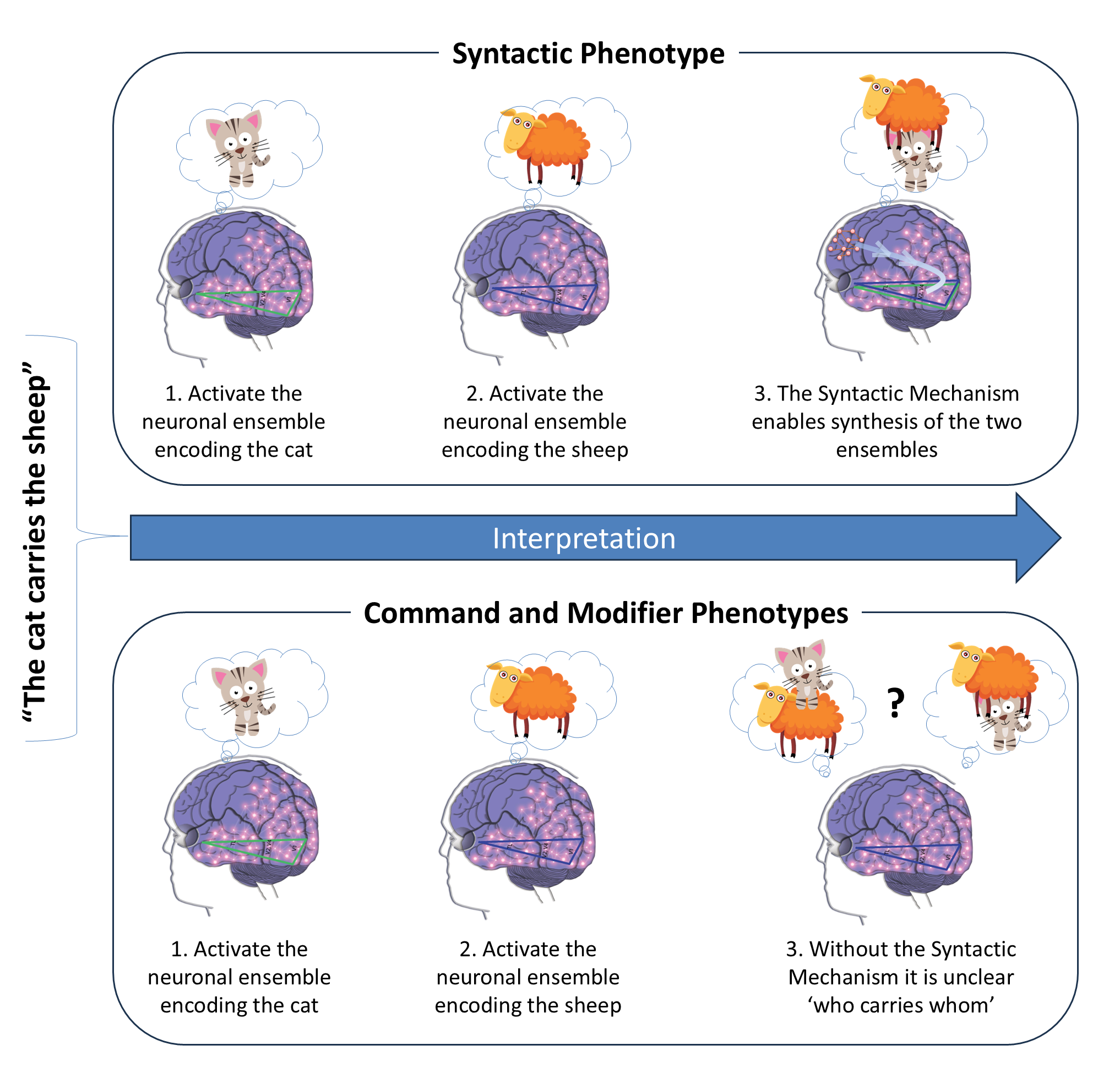

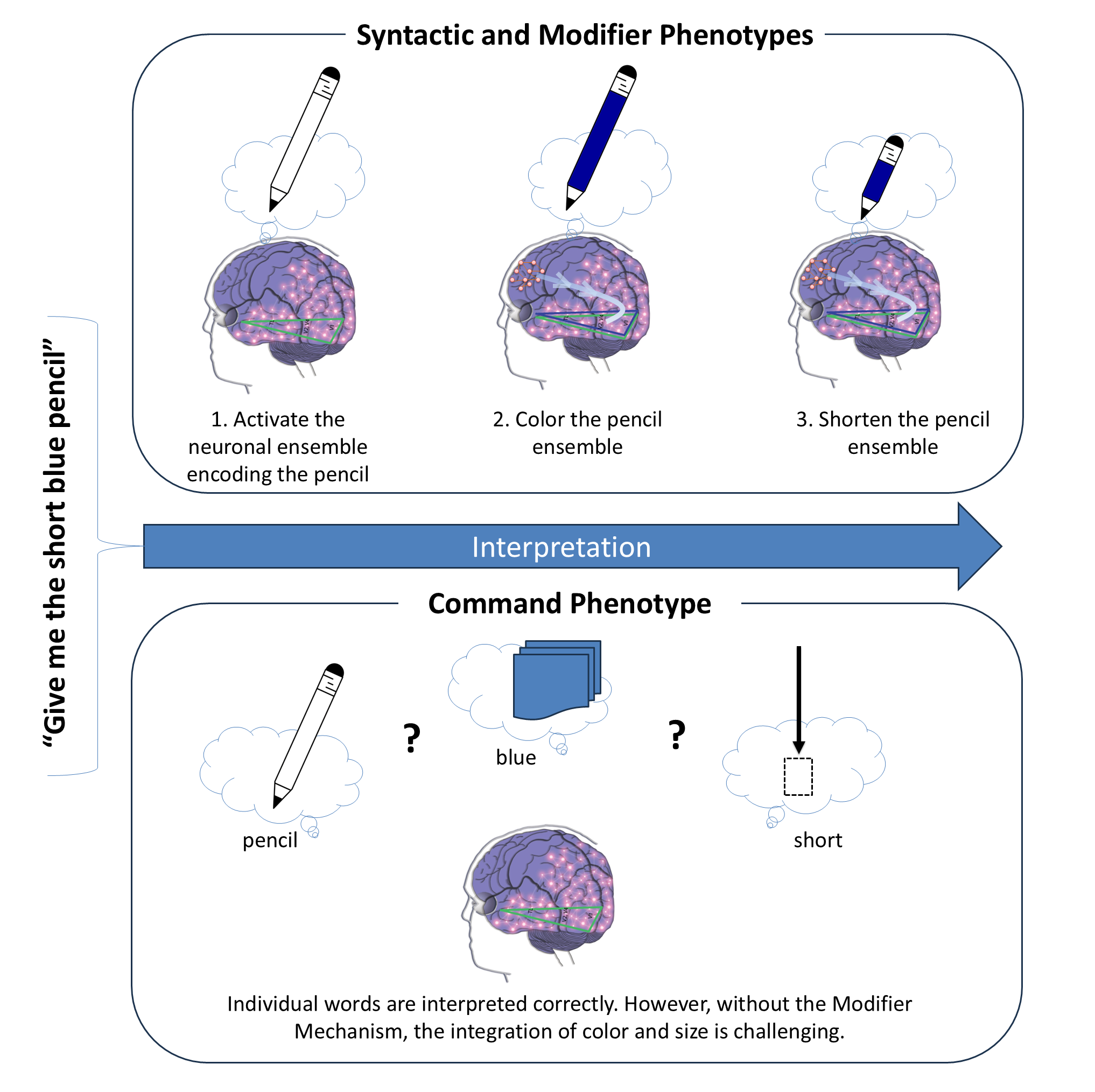

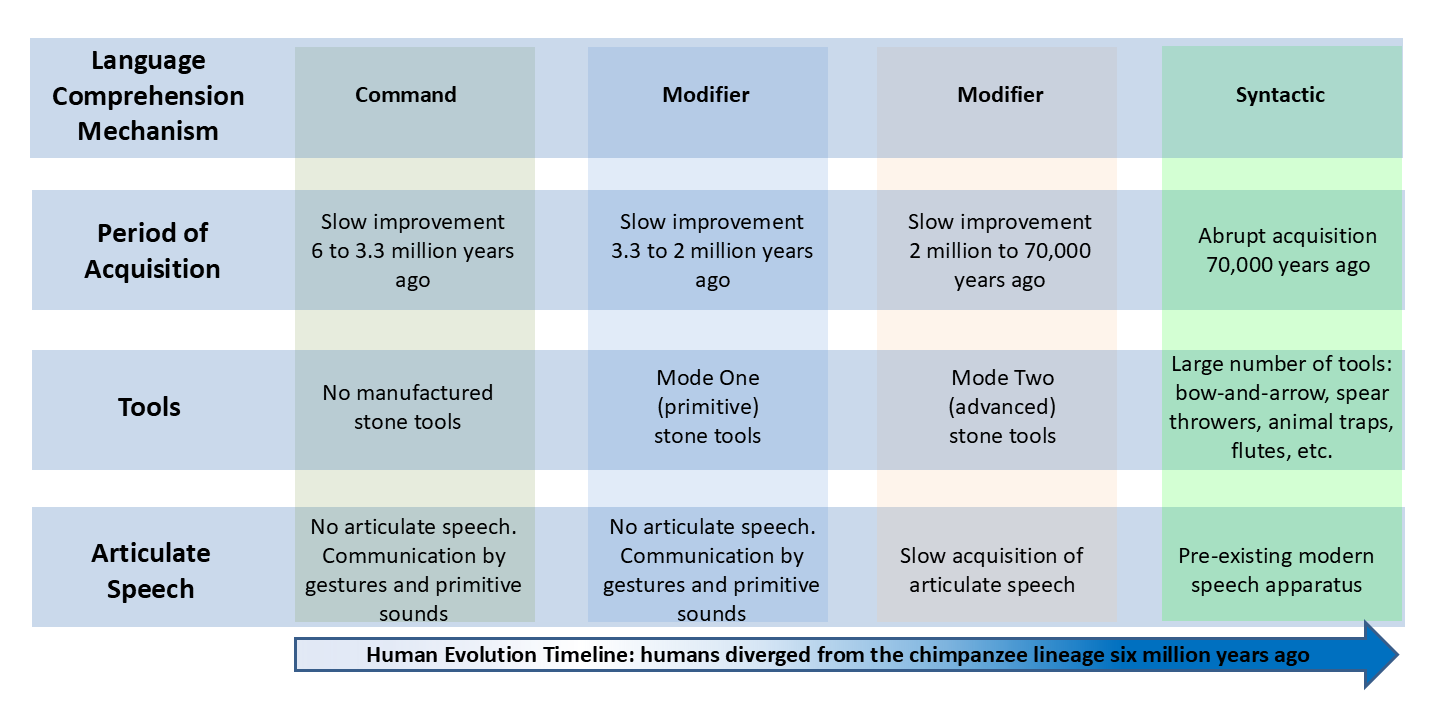

Over two decades ago, I investigated the neurobiology of language and predicted the existence of three distinct language comprehension mechanisms: two uniquely human and one shared with other primates. Now, leveraging data from tens of thousands of individuals with language deficits, my team and I have empirically confirmed the existence of all three mechanisms. The most-basic is the Command Mechanism, which enables understanding of single words and simple commands. The next level, the Modifier Mechanism, allows comprehension of combinations involving nouns and their modifiers, such as color, size, and number (e.g., “Give me a long red pencil” from a selection of straws, pencils, and Legos of varying colors and sizes). The most-advanced, the Syntactic Mechanism mediates comprehension of spatial prepositions, verb tenses, flexible syntax, possessive pronouns, and complex narratives such as stories and fairy tales.

Children typically acquire the Command Mechanism by around two years of age, the Modifier Mechanism by three years, and the Syntactic Mechanism by four years. However, various neurological conditions can restrict some individuals to acquiring only the Command Mechanism or only the Command and Modifier Mechanisms, leading to lifelong language comprehension deficits.

The Command Mechanism is the only one demonstrated in non-human animals; no animal has shown the ability to understand instructions like "Give me a long red pencil" or comprehend a fairytale. Thus, our findings are consistent with Chomsky's hypothesis regarding the existence of a uniquely human language comprehension mechanism. Furthermore, our results refine Chomsky's hypothesis by distinguishing two uniquely human language comprehension mechanisms: the Modifier Mechanism and the Syntactic Mechanism. More importantly, we present a neurological model of these mechanisms, offering a comprehensive framework for understanding human language comprehension.

Clinical implications

This discovery has potential to enhance the treatment of individuals with language deficits by enabling more precise characterization of language comprehension phenotypes—whether Command, Modifier, or Syntactic—and by tailoring language therapy to address the full spectrum of language mechanisms. Furthermore, the neurological model of language comprehension opens new avenues for developing pharmacological interventions aimed at extending the critical period for language comprehension learning beyond early childhood.

Human language evolution

An intriguing aspect of our discovery lies in its implications for the study of the evolution of human language. A key advantage of understanding the neurological basis of these mechanisms is the ability to link language comprehension (which leaves no physical trace) to dated archeological artifacts. This connection provides a means of estimating when each language comprehension mechanism emerged.

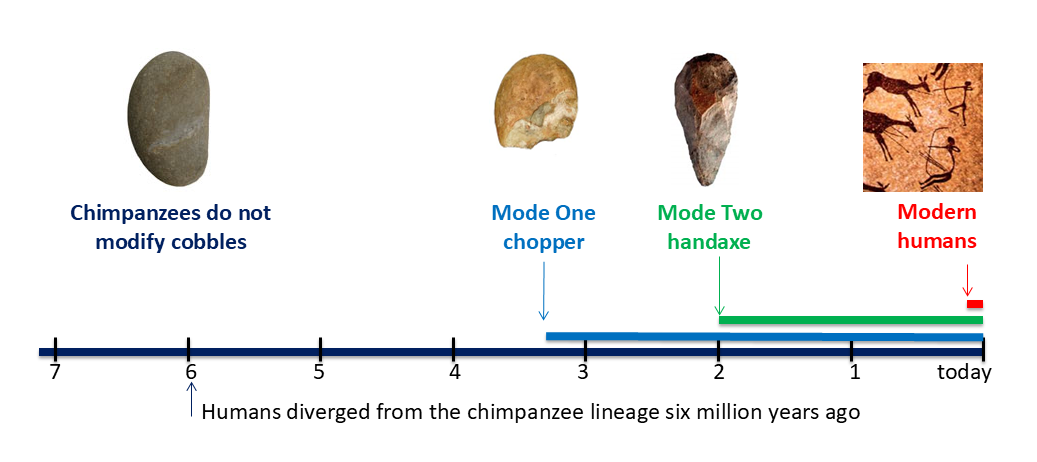

Based on neurobiological insights, we proposed that the Syntactic Mechanism arose around 70,000 years ago, coinciding with the cognitive revolution. This transformative period saw the sudden emergence of composite figurative art, bone needles with an eye, grave goods, a shift in hunting strategies to include animal trapping, and the ability to cross open water to reach Australia.

From a neurological perspective, the manufacturing of stone tools is strongly related to the Modifier Mechanism of language comprehension. A handaxe cannot be manufactured by randomly striking of a cobble. Stone tools manufacturing requires a mental template in the mind of a toolmaker that determines the eventual form of the tool. Even if one has previously seen a handaxe and could recall it from memory, this memory cannot serve directly as a mental template. Rather, it must be mentally modified/re-sized, to account for the unique features of each cobble. This neurological mechanism for deliberate re-sizing a mental object is also essential for comprehension of sentences that communicate modification of an object’s size (e.g., “give me a bigger stone” or “give me a smallest stick”). Consequently, the manufacturing of Mode One choppers approximately 3.3 million years ago marks the emergence of the Modifier Mechanism. The gradual evolution of stone tool technology reflects the progressive refinement of this mechanism. The transition from crude Mode One choppers to symmetrical Mode Two handaxes with extended cutting edges around 2 million years ago provides a confirmation of the steady development of the Modifier Mechanism of language comprehension.

The Modifier Mechanism facilitated acquisition of articulate speech

One of the most surprising findings of our research is the relationship between the acquisition of articulate speech and various mechanisms of language comprehension. Multiple lines of evidence suggest that the development of the articulate speech apparatus began around 2 million years ago, indicating that the uniquely human modifier mechanism of language comprehension was acquired prior to the emergence of articulate speech. This raises the intriguing possibility that for over a million years, our ancestors relied on hand gestures for communication of modifiers such as size and number. Moreover, it suggests that the Modifier Mechanism may have played a crucial role in facilitating the acquisition of articulate speech. It is likely that it was the gradual neurological development of the Modifier Mechanism, communicated through gestures, that set humans on the path to articulate speech and eventually to the acquisition of syntactic language.

Our research highlights that human language extends beyond speech to encompass multiple mechanisms of language comprehension. This understanding not only aids individuals with language deficits in reaching their full potential but also deepens our appreciation of what makes human language unique, shedding light on its evolutionary development.

Follow the Topic

-

npj Science of Learning

An online open access peer-reviewed journal dedicated to research on all aspects of learning and memory – from the genetic, cellular and molecular basis, to understanding how children and adults learn through experience and formal educational practices.

Your space to connect: The Psychedelics Hub

A new Communities’ space to connect, collaborate, and explore research on Psychotherapy, Clinical Psychology, and Neuroscience!

Continue reading announcementRelated Collections

With Collections, you can get published faster and increase your visibility.

Effects of lifestyle behaviours on learning and neuroplasticity

Publishing Model: Open Access

Deadline: Mar 09, 2026

Reimagining Teaching and Learning in the Age of Generative AI Agents

Publishing Model: Open Access

Deadline: Jul 13, 2026

Please sign in or register for FREE

If you are a registered user on Research Communities by Springer Nature, please sign in