Together, we are strong(er): a bacterial community boosts production of bioplastics by an engineered cyanobacterium

Published in Bioengineering & Biotechnology, Materials, and Microbiology

Despite efforts to curtail the production and use of fossil-derived plastics, their global production continues to increase by 10% each year and could reach 1124 million metric tons by 2050 [1]. From electrical and electronic equipment to food packaging and food-related objects, plastics are everywhere and here to stay. Their degradation can take hundreds of years, and, even when degraded, large plastic objects remain in the environment as tiny particles called microplastics (< 5 mm in diameter). The environmental impact is appalling: in the oceans, on land, and in the air, where they accumulate, microplastics damage marine and terrestrial ecosystems. They don´t spare us humans: through ingestion or inhalation, microplastics make their way into the human body, where they are suspected of contributing to various pathologies, including cardiovascular diseases [2].

Alternatives to fossil-based plastics exist, but bio-based and biodegradable plastics, known as bioplastics, still account for only 1% of the total annual plastic production [1]. Examples of bioplastics are polyhydroxyalkanoate (PHA) polymers, which are naturally produced by various bacteria under nutrient-limited conditions. Thanks to their unique properties, PHA-based polymers are promising substitutes for petrochemical-based plastics [3, 4]. At an industrial scale, their production currently relies on fermentation carried out by heterotrophic bacteria. However, during this process, bacteria consume crop-derived carbon compounds, which raises sustainability concerns. A more environmentally friendly way to produce PHA is based on the use of phototrophic microorganisms, so-called cyanobacteria or green-blue algae, which harness light energy and atmospheric CO₂ to grow and produce PHB.

In the laboratory of Professor Karl Forchhammer at the University of Tuebingen, Germany, the model cyanobacterium Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803 (Synechocystis from now on) has long been studied to optimize the production of a particular type of PHA, polyhydroxybutyrate (PHB). When nitrogen-starved, Synechocystis stops growing and produces PHB polymers, which accumulate in granules and serve as carbon stores. Back in 2020, the lab succeeded in genetically modifying a Synechocystis strain (PPT1) to increase the yield of PHB up to 60% relative to cell dry weight (CDW) (Figure 1). However, because PHB production is incompatible with growth, the overall productivity remained limited to 5 mg/L per day [5]. Since then, attempts to cultivate Synechocystis PPT1 at a pre-industrial scale for PHB production have failed because cultures of the strain in isolation are sensitive to environmental stresses such as fluctuating light intensity and temperature shifts, which are often encountered in large-scale cultivation settings.

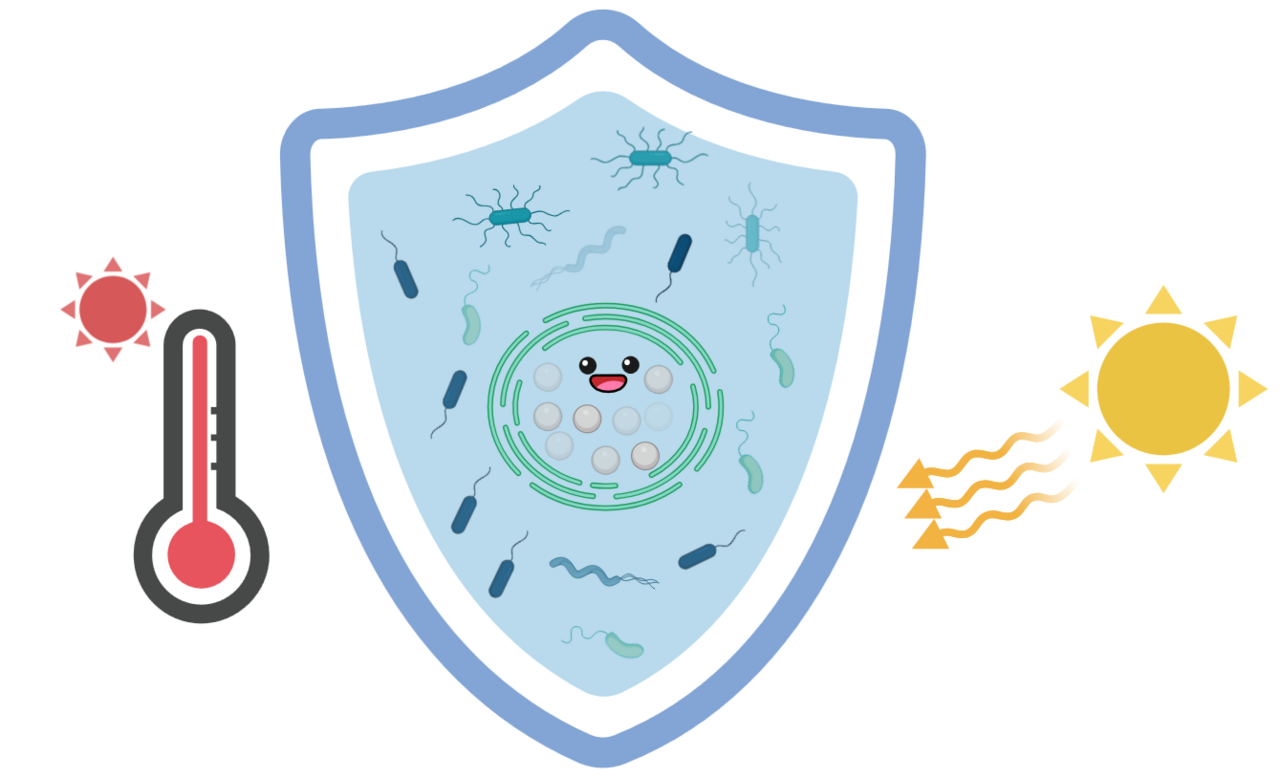

To overcome these shortcomings, natural bacterial communities (microbiomes) that are enriched in cyanobacteria have recently gained momentum for producing PHB, based on the observation that natural microbiomes are more resilient than isolated microbes to environmental stresses. Building on this, Prof. Forchhammer and PhD student Arianna Zini sought to test the performance of the engineered Synechocystis PPT1 strain within communities. For this, they cultivated PPT1 with the non-photosynthetic fraction of a natural, cyanobacteria-enriched microbiome isolated by Altamira-Algarra and colleagues [6], thus ensuring that PPT1 was the only cyanobacterium and photosynthetic microbe within the community. Compared to a consortium containing a non-engineered Synechocystis strain, which produced around 15% PHB relative to CDW, the PPT1-containing consortium (hereafter referred to as PPHET) reached up to 48% PHB/CDW, with a productivity of 35 mg/L per day. Interestingly, PHB production was not or only slightly affected when the PPHET consortium was challenged with high-light intensities or temperature stress, respectively. In contrast, PHB production collapsed in cultures of PPT1 in isolation. This motivated Arianna to test pre-industrial conditions, scaling up the culture of the PPHET consortium from 50 ml to 10 L. Even under these conditions, the consortium demonstrated robustness for upscaling scenarios and accumulated 33% PHB relative to CDW. Analysis of community composition revealed that the consortium was dominated by PPT1 and was enriched in heterotrophic bacterial species that are commonly found in association with cyanobacteria in nature.

Overall, the study published in Microbial Biotechnology indicates that engineered natural consortia are more suitable for bioplastic production than isolated strains. Community members likely provide essential micronutrients and antioxidants to support the growth of and protect PPT1 from oxidative stress. In turn, PPT1 likely shares the products of photosynthesis, sugars, and oxygen, with non-photosynthetic bacteria, in a win-win situation. Looking ahead, Arianna is planning to engineer defined communities where, similar to assembly lines, each member contributes to step-wise PHB production.

While this work paves the way for the use of engineered natural consortia in sustainable bioplastic manufacturing, it may still take some time before bioplastics entirely replace fossil-derived plastics. In the meantime, let us continue to reduce our use of plastics and recycle them. Individual efforts can make a difference. Together, we are stronger.

References

- Gautam, S., et al., Current Status and Challenges in the Commercial Production of Polyhydroxyalkanoate-Based Bioplastic: A Review. Processes, 2024. 12(8): p. 1720.

- Microplastics are everywhere - we need to understand how they affect human health. Nat Med, 2024. 30(4): p. 913.

- Getino, L., J.L. Martín, and A. Chamizo-Ampudia, A Review of Polyhydroxyalkanoates: Characterization, Production, and Application from Waste. Microorganisms, 2024. 12(10): p. 2028.

- Ren, Q., et al., Properties of Engineered Poly-3-Hydroxyalkanoates Produced in Recombinant <i>Escherichia coli</i>Strains. Applied and Environmental Microbiology, 2000. 66(4): p. 1311-1320.

- Koch, M., et al., Maximizing PHB content in Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803: a new metabolic engineering strategy based on the regulator PirC. Microb Cell Fact, 2020. 19(1): p. 231.

- Altamira-Algarra, B., et al., Bioplastic production by harnessing cyanobacteria-rich microbiomes for long-term synthesis. Sci Total Environ, 2024. 954: p. 176136.

Please sign in or register for FREE

If you are a registered user on Research Communities by Springer Nature, please sign in