Under the microscope: Trichinella revealed

Published in Microbiology

An Overview of Trichinella

Nematode parasites of the genus Trichinella vary geographically and in their hosts. They have been reported on every continent except Antarctica, and are widespread in colder arctic and subarctic climates like that of Canada, Alaska and Greenland in North America, and in Northen Europe. Some species, like Trichinella spiralis, use swine (both wild and domesticated) as hosts. This species can infect humans via the consumption of infected pig meat. Other species, those that piqued my interest, have a sylvatic transmission cycle (within wild animals) with hosts including lynx, bears, wolves and foxes.

image: The British Museum

The main reservoir of most Trichinella species is wild carnivores, where they reside within the animals’ muscle. Unlike many parasites, the first-stage larvae (L1) are the infecting larvae rather than the L3 stage, and uniquely, Trichinella spends its entire natural life cycle within the host. This means that the parasite is transmitted through consumption via carnivory or scavenging. The longer the larvae can remain viable in the animal carcass muscle the higher the chance of transmission to the next host. Therefore, some species (like T. nativa) have adapted an anaerobic metabolism for surviving in a carcass, and they have also become resistant to freezing. This means that larvae can persist for months or even years in the animals’ carcasses waiting for a scavenger to feed on the infected meat. Consequently, freezing as a food safety technique is ineffective at inactivating Trichinella spp. In fact, in July 2022, a Trichinella patient in the US had his infection traced back to black bear meat that had been served rare after being frozen for 45 days. The risk of transmission to humans is therefore higher in regions where wild animals are commonly consumed, with black bear meat being the leading cause of human infections in North America.

Insights from a recent study

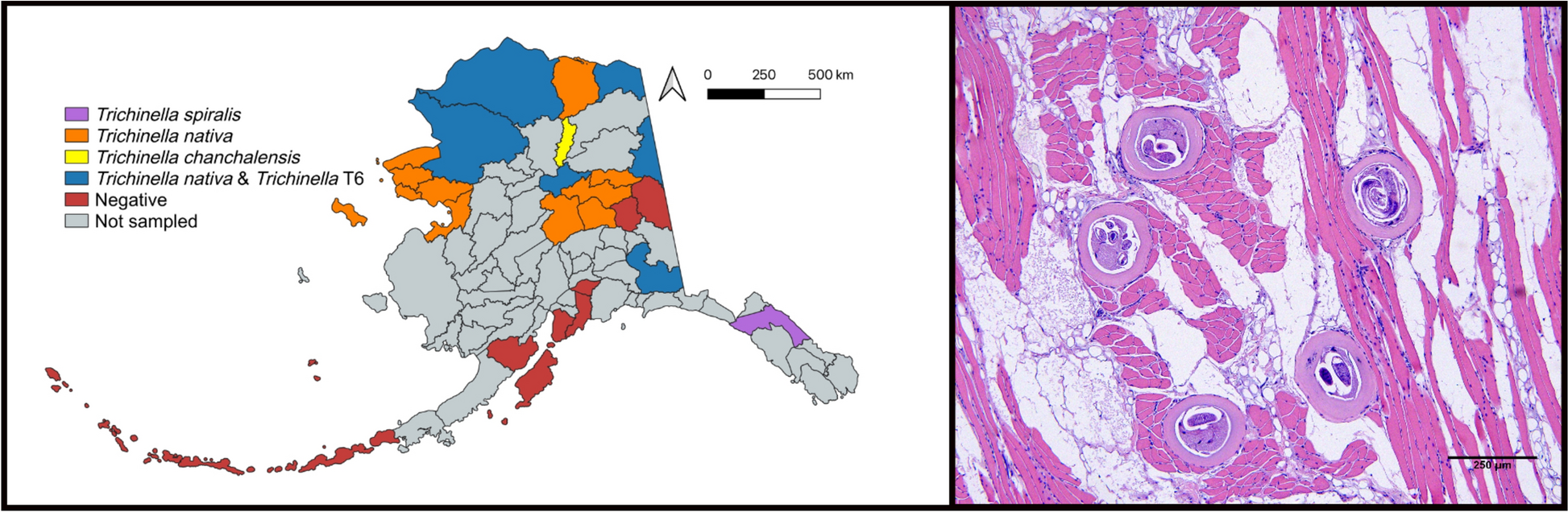

A recent study by Malone et al. describes the prevalence, co-infection and geographic distribution of several Trichinella species in North America, including Trichinella chanchalensis, the newest described species. As well as gathering general information about infection levels in animals across the region, they wanted to see if Trichinella chancalensis, first described in the Yukon and Northwest Territories in Canada, was present in Alaska. These two areas share a long border with not much of a geographical barrier between the two, so it’s likely the species would be able to cross over to Alaska. Using next-generation sequencing to genotype larvae from the muscles of various dead carnivores the authors described the infection levels across 53 animals. The study found Trichinella species of the genotypes T. nativa, Trichinella T6, and T. chanchalensis in around a third of the animals tested. They found the highest prevalence of Trichinella in wolverines and polar bears, the highest larvae per gram in arctic foxes, red foxes, and wolves, and surprisingly no infection in the black bears or lynx tested. T. nativa was the species with the highest overall prevalence.

A particularly interesting finding was the presence of T. spiralis of suspected foreign origin in one brown bear. As previously mentioned, this species is usually found in domestic pigs which are uncommon where the bear was found, and in fact this species was considered eliminated in the US and Canada. The authors posit that the bear had consumed meat or animals illegally imported into the country, a practice that can pose a public health threat, introducing new parasites or reintroducing eradicated parasites to an area. The authors found that 50% of the T. spiralis larvae found in the brown bear were tightly coiled, suggesting viability, despite the muscle having been frozen for 3.5 years! Regarding Trichinella chanchalensis, infection was detected in a wolverine from Alaska, the first time this species has been reported outside of Canada. But with the two places having similar climates and the absence of a notable geographic border, it is surprising that the species was only found once in Alaska.

Conclusion

The nematode Trichinella has an interesting life cycle, and a remarkable ability to tolerate being frozen. Pigs are one host of Trichinella spp e.g., T. spiralis. But as Malone et al. reported, hosts of Trichinella spp also include an array of wild carnivores. Human infection from the consumption of pig meat was historically high, with almost 1 in 6 people in the US testing positive for Trichinella in the 1930s. However, as food safety standards and testing increased, human infection from pigs decreased. On the other hand, the consumption of wild carnivores is not widespread, so the transmission of Trichinella from these hosts is less common. However, where these species are consumed more regularly Trichinella do pose a public health risk since freezing meat will not inactive the nematode, and only adequate cooking will kill this parasite.

Follow the Topic

-

Parasites & Vectors

This journal publishes articles on the biology of parasites, parasitic diseases, intermediate hosts, vectors and vector-borne pathogens.

-

BugBitten

A blog for the parasitology and vector biology community.

Related Collections

With Collections, you can get published faster and increase your visibility.

Credelio Quattro

Articles published in the collection have already gone through the systematic peer review process of the journal.

Publishing Model: Open Access

Deadline: Apr 24, 2026

Molecular biology of disease vectors

Parasites & Vectors is calling for submissions to our Collection on 'Molecular biology of disease vectors.' Vector-borne diseases such as Chagas disease, dengue and chikungunya, human African trypanosomiasis, leishmaniasis, lymphatic filariasis, onchocerciasis and schistosomiasis, are among the WHO neglected tropical diseases, and associated with devastating health, social and economic consequences. Studying various aspects of disease vectors is a fundamental step towards the control of these diseases. This collection contains articles from keynote speakers presenting at the 10th Workshop on Genetics and Molecular Biology of Insect Vectors of Tropical Diseases (Entomol10), held during the 59th Congress of the Brazilian Society of Tropical Medicine, São Paulo, Brazil.

The collection is also open to submissions on molecular biology (e.g., population genetics, phylogenetics and evolution, molecular taxonomy, and vector-pathogen interactions), surveillance and control of disease vectors.

Publishing Model: Open Access

Deadline: Feb 28, 2026

Please sign in or register for FREE

If you are a registered user on Research Communities by Springer Nature, please sign in