Understanding Alzheimer’s: A Promising Lead with Nanobodies

Published in Neuroscience and Cell & Molecular Biology

One of the key features of neurodegenerative diseases like Alzheimer’s is the abnormal buildup of certain proteins in the brain. These proteins clump together inside neurons, disrupting their normal function. In Alzheimer’s, the troublemaker is a protein called tau.

Normally, tau helps maintain the internal structure of cells. But in Alzheimer’s, it forms thread-like tangles inside neurons. This buildup leads to cell malfunction and eventually cell death—contributing to memory loss and other cognitive problems.

What’s even more concerning is that tau might behave like a prion—a misfolded protein that contaminate others and force them to fold abnormally in turn. This ability is associated with propagation from cell to cell, which could explain why Alzheimer's disease gradually spreads through the brain.

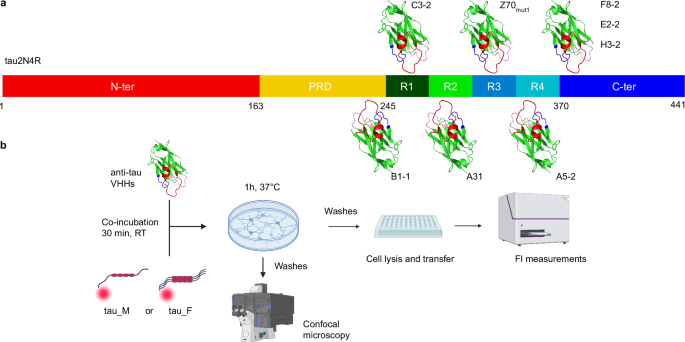

That’s where a fascinating research project began, led by Clément Danis at the end of his PhD. He was investigating whether tiny antibody fragments called nanobodies™—specially designed to recognize tau—could enter neurons on their own.

To test this, he grew mouse neurons in the lab and added anti-tau nanobodies to the environment, with and without tau. The idea was that if tau could get into cells, maybe the nanobodies could hitch a ride. But it didn’t work: the nanobodies didn’t enter the neurons, even when tau was present.

Then came a surprising twist: some nanobodies blocked tau from entering the cells. Not all of them, but a few clearly had this effect. This raised a big question: why could some nanobodies block tau while others couldn’t?

The early experiments weren’t designed to answer that—each nanobody targeted a different part of the tau protein with varying strength. But luckily, the team had a large collection of nanobodies ready for further study.

While Clément moved on to a postdoc, the research continued. One nanobody in particular—called H3-2—stood out. It had the strongest binding to tau and effectively blocked it from entering neurons. Structural analysis of H3-2 revealed a jaw-dropping surprise: it formed a unique “dimer” shape, like two nanobodies locking arms in an unusual configuration—something not seen before.

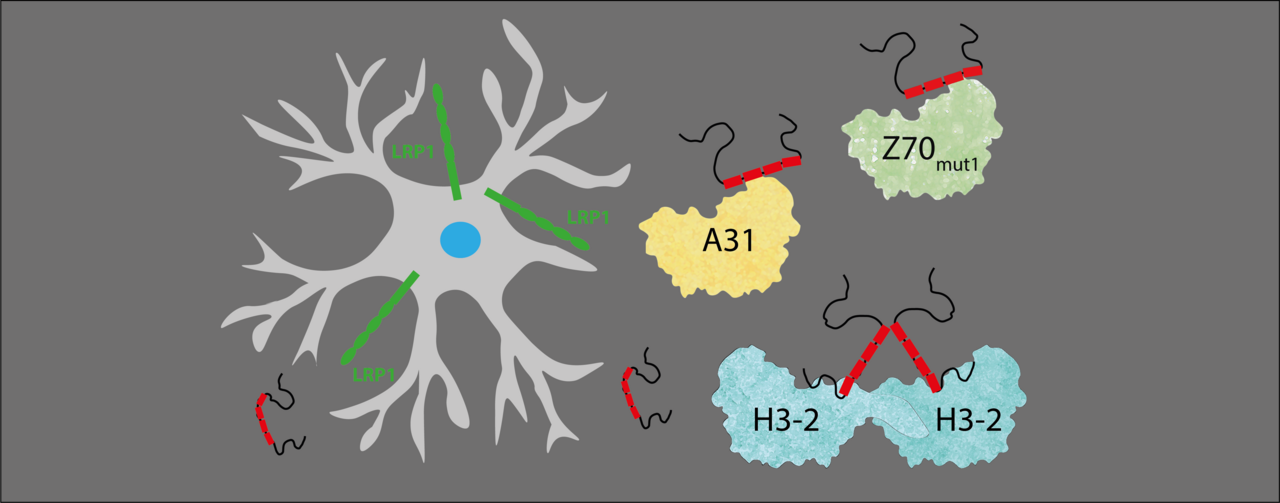

Meanwhile, the team developed even more powerful anti-tau nanobodies. When Clément returned, the timing was perfect. The scientific community had also made progress in understanding how proteins like tau enter cells—especially the role of a membrane receptor called LRP1.

With new tools and better insight, the team showed that anti-tau nanobodies could block the interaction between tau and LRP1, preventing tau from entering neurons. Once again, H3-2 stood out, not only blocking monomeric (free) tau, but also its clumped, fibrillar form. It indeed reduced tau fibril’s ability to interact with heparan sulfate proteoglycans (HSPGs), another route tau uses to get into cells.

These findings revealed something important: tau uses different pathways to enter cells depending on its form, and certain nanobodies can block both.

Why does this matter? Because many anti-tau antibody therapies tested in clinical trials have failed—often due to poor target engagement or lack of efficacy. Nanobodies could offer a smarter, more precise way to understand how tau spread through the brain, and how to stop it.

In short, this research shows how a simple lab question can lead to big insights into a complex disease. Nanobodies might one day help us stop Alzheimer’s at its roots—by blocking the very mechanisms that allow it to spread.

Follow the Topic

-

Nature Communications

An open access, multidisciplinary journal dedicated to publishing high-quality research in all areas of the biological, health, physical, chemical and Earth sciences.

Related Collections

With Collections, you can get published faster and increase your visibility.

Women's Health

Publishing Model: Hybrid

Deadline: Ongoing

Advances in neurodegenerative diseases

Publishing Model: Hybrid

Deadline: Mar 24, 2026

Please sign in or register for FREE

If you are a registered user on Research Communities by Springer Nature, please sign in