Unravelling the Mystery of Millipede Nutrition: Understanding the Role of Their Gut Microbiota

Published in Ecology & Evolution, Microbiology, and Agricultural & Food Science

In soil ecology, millipedes have long been recognised as crucial detritivores, playing a pivotal role in the decomposition of plant litter and the cycling of nutrients in terrestrial ecosystems.

The prevailing hypothesis in millipede biology posited that, like many other detritivores, millipedes rely heavily on their gut microbiome to break down recalcitrant plant polymers, particularly cellulose. This idea was consistent with our knowledge of other detritivorous and xylophagous animals, where microorganisms in the gut play a vital role in the hydrolysis and fermentation of plant material. The assumption was that millipedes, through a process akin to that observed in termites and ruminants, utilised their gut microbiota to ferment cellulose into short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs), which could then be absorbed and used for energy.

This assumption appeared reasonable, considering the low nutrient content of the main food supply for millipedes – decaying plant matter and dead tree bark. The concept that millipedes had developed a mutually beneficial relationship with their gut microorganisms to obtain the highest possible nutritional value from such resistant food sources was compelling. However, as is often the case in science, a closer examination has revealed a more complex and nuanced reality.

In previous studies, it was found that fermentation takes place in the guts of millipedes, and some millipedes (but not all) produce methane in their guts due to methanogens. However, it remained unclear whether millipedes actually benefit from fermentation. In our current research, we aimed to better understand the relationship between millipedes and their gut microbiota. The study focused on two distinct millipede species: the tropical, methane-emitting Epibolus pulchripes and the temperate, non-methane-emitting Glomeris connexa. This choice of species allowed for a comparison between millipedes with different gut physiologies and metabolic outputs.

Epibolus pulchripes (left) and Glomeris connexa (right). Credit: V. Šustr.

We employed a multifaceted approach, combining classic microbiological techniques using inhibitors, fluorescent microscopy, and stable isotope probing to address the question of gut microbiota function from multiple angles.

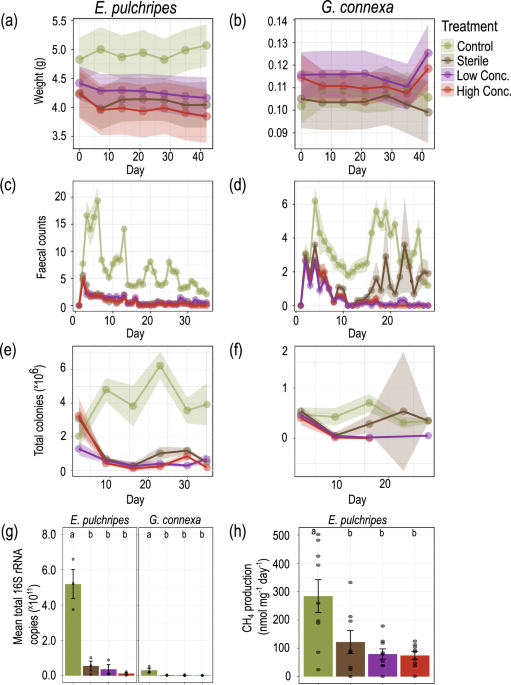

In the first phase of the study, we subjected both millipede species to antibiotic treatment, effectively disrupting their gut microbiota. This treatment resulted in a dramatic reduction in both the viable bacterial count and the total microbial load in the millipedes' faeces. Surprisingly, despite this significant perturbation of their gut microbiota, the millipedes showed minimal changes in survival rates or body weight. This unexpected resilience in the face of gut microbiota disruption was the first indication that the relationship between millipedes and their gut microbes might not be as straightforward as previously thought.

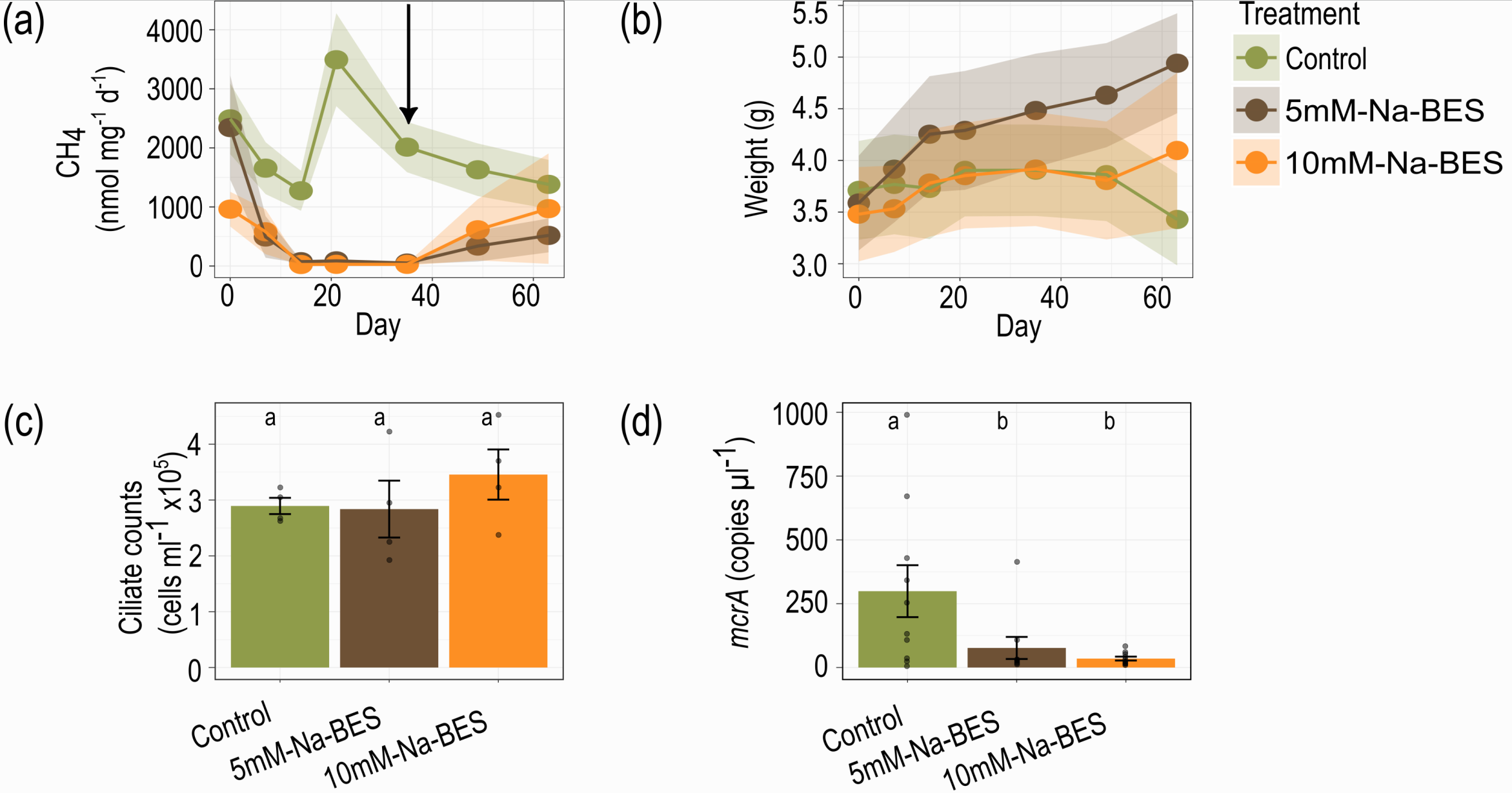

We then turned our attention to the phenomenon of methanogenesis in E. pulchripes. Methane production, carried out by archaeal methanogens, is associated with anaerobic fermentation in gut systems. By treating the millipedes' food with a specific methanogenesis inhibitor, we could completely halt methane production and reinitiate it after returning the animals to an unamended diet. Remarkably, blocking methanogenesis had no discernible effect on the millipedes' weight or survival. This finding further undermined the hypothesis that fermentation products are crucial in millipede nutrition and raised intriguing questions about the ecological significance of methanogenesis in these arthropods.

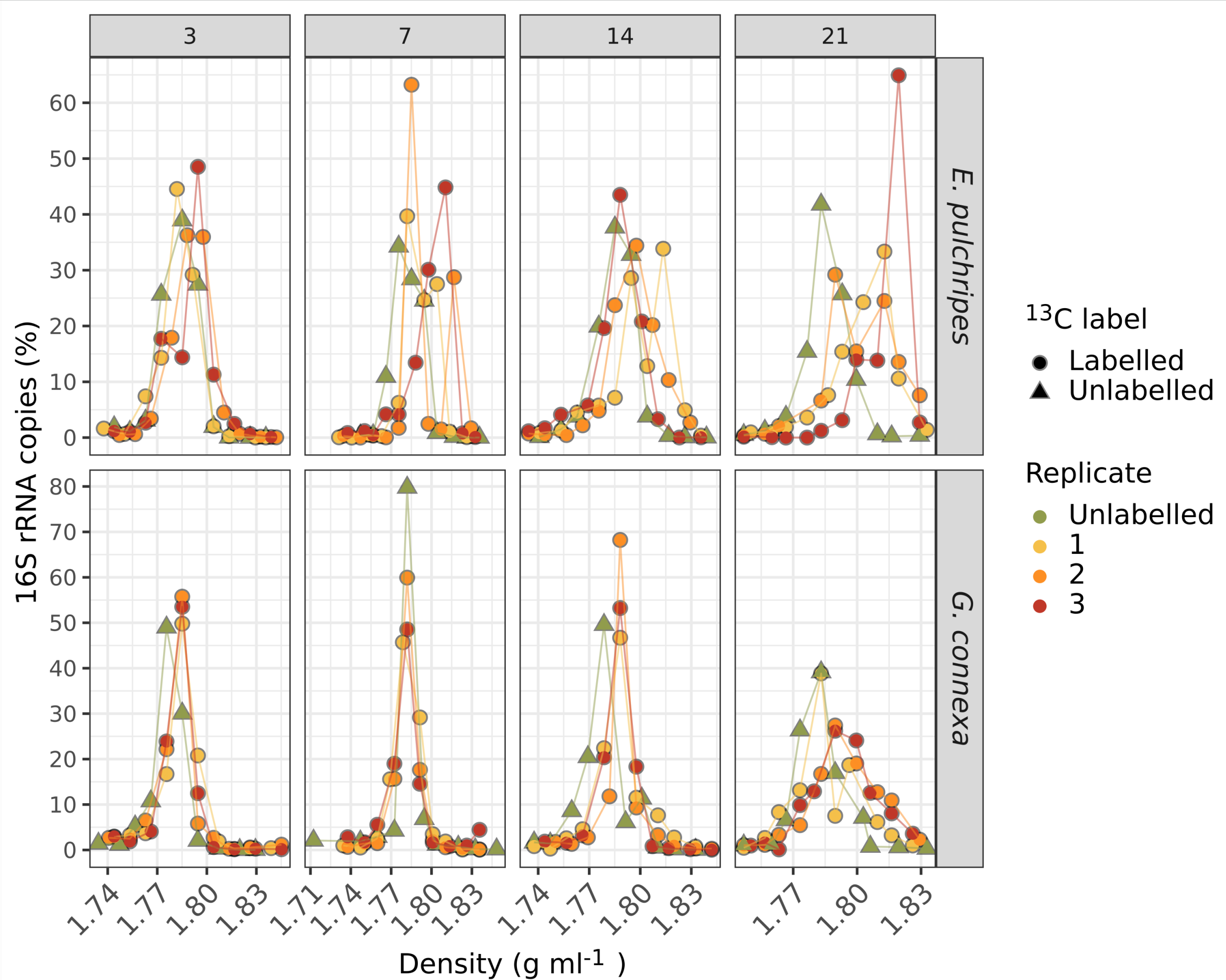

One of the most revealing aspects of the study was the use of stable isotope probing (SIP) with 13C-labelled leaf litter. This technique allowed us to track the flow of carbon from the leaf litter through the gut and into the microbial biomass. The results of the SIP experiment were surprising. Contrary to our expectations, labelling prokaryotic RNA in the millipede gut was a slow and gradual process. Even after 21 days of feeding on fully labelled litter, a significant portion of the prokaryotic RNA remained unlabelled. This slow incorporation of the isotopic label suggests that the gut bacteria are not rapidly metabolising and incorporating carbon from the leaf litter, as would be expected if the gut was a degradation hotspot.

Intriguingly, the fungal biomass in the millipede gut, particularly in G. connex, showed faster and more extensive labelling than the prokaryotic biomass. This observation aligns with patterns seen in soil litter decomposition, where fungi are often the primary colonisers of recalcitrant, nutrient-poor litter. At the same time, bacteria tend to dominate in later stages when more labile organic matter becomes available.

The cumulative evidence from these experiments suggests that the role of gut microbiota in millipede nutrition is not as central as previously believed. If millipedes do not rely heavily on the products of cellulose fermentation by their gut microbiota, what then is their primary source of nutrition? Based on these findings and our previously published metagenome and metatranscriptome-based works, we propose that the millipedes' nutrition is based on a combination of the following:

1. Preferential Digestion of Microbial and Fungal Biomass: Millipedes may primarily consume the bacteria and fungi that colonise the leaf litter rather than directly digesting plant material. This would explain the faster labelling of fungal biomass observed in the SIP experiments.

2. Utilisation of Non-structural Plant Components: Millipedes produce endogenous enzymes capable of breaking down some plant components. These enzymes, which are secreted in the salivary glands and midgut, may be sufficient for digesting more easily accessible plant nutrients.

3. Coprophagy as a Nutritional Strategy: The practice of reingesting faeces, known as coprophagy, may allow millipedes to access fresh microbial and fungal biomass resulting from the partial breakdown of plant material during its first passage through the gut.

Although this study challenges the notion that the gut microbiota is central to millipede nutrition, it does not negate the importance of these microbes. We suggest several other potential functions for the gut microbiota in millipedes:

1. Detoxification of Plant Secondary Metabolites: Many plants produce toxic compounds to defend against herbivory. The gut microbiota may play a role in detoxifying these compounds, allowing millipedes to consume a wider range of plant material safely.

2. Production of Essential Compounds: The gut microbiota may synthesise essential nutrients or cofactors not readily available in the millipedes' diet.

3. Pathogen Protection: The resident gut microbiota likely plays a role in protecting the millipede against potential pathogens, either through competitive exclusion or by stimulating the host's immune system.

4. Horizontal Gene Transfer: The gut environment may facilitate horizontal gene transfer between microorganisms and potentially even to the host, providing a mechanism for rapid adaptation to new food sources.

In our future work, we will continue to explore the roles of the gut microbiome in millipedes and other soil arthropods in nutrient acquisition, greenhouse gas emissions, and carbon stabilisation in the soil.

Follow the Topic

-

Communications Biology

An open access journal from Nature Portfolio publishing high-quality research, reviews and commentary in all areas of the biological sciences, representing significant advances and bringing new biological insight to a specialized area of research.

Related Collections

With Collections, you can get published faster and increase your visibility.

Signalling Pathways of Innate Immunity

Publishing Model: Hybrid

Deadline: Feb 28, 2026

Forces in Cell Biology

Publishing Model: Open Access

Deadline: Apr 30, 2026

Please sign in or register for FREE

If you are a registered user on Research Communities by Springer Nature, please sign in