Using WhatsApp chats to understand a new approach to HIV testing in children.

Published in Healthcare & Nursing

Improving HIV testing for children and adolescents is vitally important, because children and adolescents experience a disproportionate amount of HIV-related illness and death compared to adults. Although children and adolescents aged up to 19 years old were only 7% of the global population living with HIV in 2021, they represented 17% of HIV-related deaths. This is due, in part, to late diagnosis of HIV.

A new approach to finding undiagnosed children living with HIV, known as index-linked testing, has been recommended by the World Health Organisation to improve diagnosis rates. Index-linked testing involves targeting of HIV testing to children of people living with HIV (known as indexes). This focused approach has the potential to find more children living with HIV and be more cost-effective than blanket testing approaches.

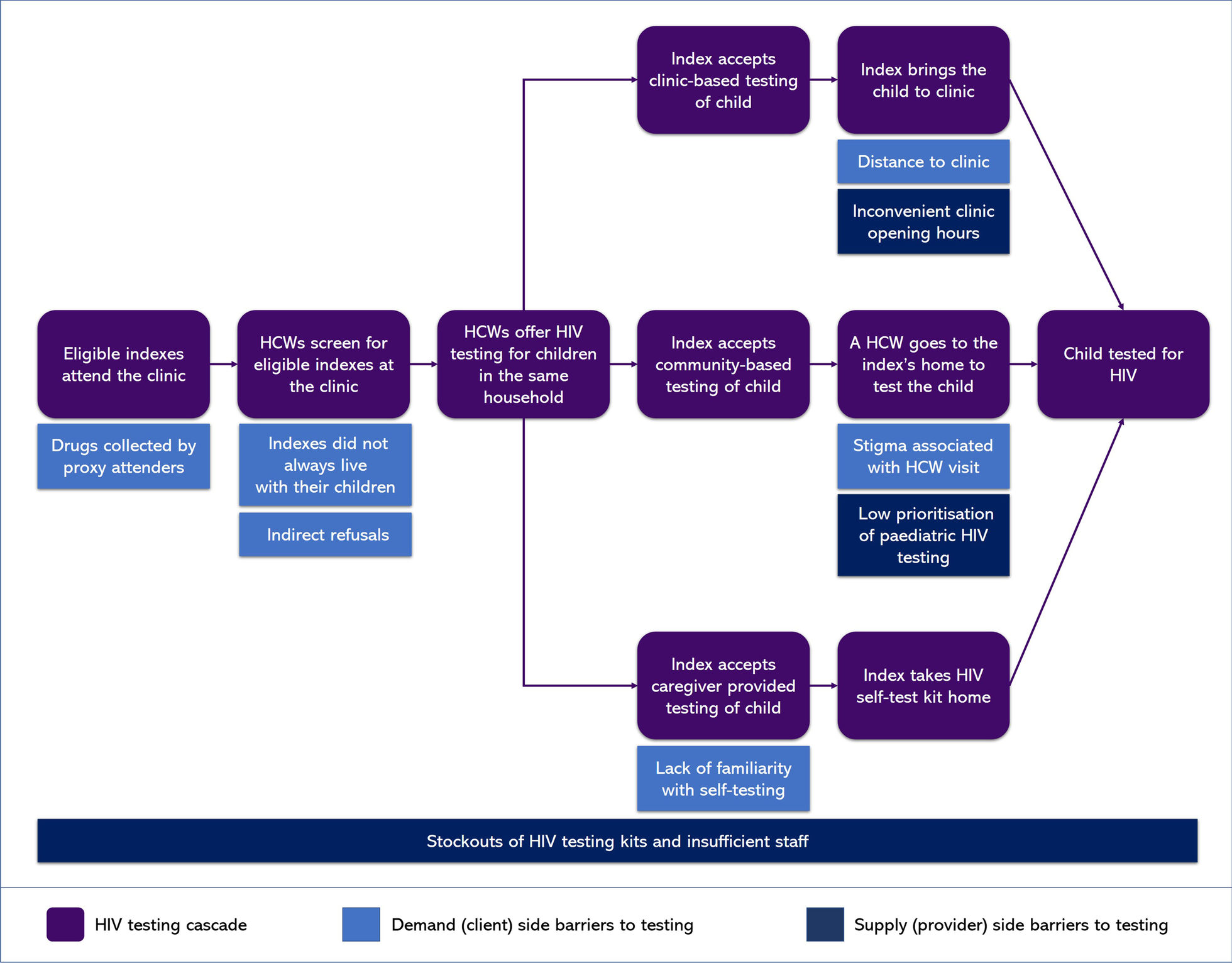

The “Bridging the Gap in HIV Testing and Care for Children in Zimbabwe” (B-GAP) study evaluated index-linked HIV testing for children aged between two and 18 years old at nine primary care clinics, covering both rural and urban areas. People living with HIV in a household with one or more children of unknown HIV status, or with a known HIV negative result more than 6 months ago, were eligible to take part in the study. Those who consented to have children tested could choose either a test at the clinic, a test at home delivered by a community healthcare worker (HCW), or a test at home delivered by a caregiver using an oral HIV self-test. B-GAP provided an opportunity to examine implementation in-depth, so lessons could be learned for future roll-out.

The B-GAP team kept in touch via two long-running WhatsApp chats, one for the whole field team, and the other for the rural areas only. We used those WhatsApp chats, as well as field team logs, meeting minutes, and incident reports, to identify barriers and facilitators to scale-up of index-linked testing. Data from each source was analysed thematically.

The WhatsApp chats deepened our understanding of implementation. In the chats, the team often offered more comprehensive opinions on successes and challenges than in other sources. For example, one chat had detailed discussion on difficulties coordinating with partner organisations who were delivering HIV testing of children in the community. This clarified the underlying reasons why these challenges were occurring, such as differences in aims between the partner organisations and the research team, as well as resource constraints faced by partner organisations. The chats also provided a real-time and dynamic account of events, such as stock-outs of HIV test kits, over time.

However, WhatsApp chats required more effort to analyse than the other sources. As the chats were an informal record, sometimes it was challenging to work out what researchers were referring to in their messages. Unlike with the other sources, the team presumed readers had prior knowledge of what was being discussed, making it difficult for an outsider to follow the conversation. Moreover, sometimes researchers met face-to-face or communicated using other technology, which led to sudden jumps in the topics being covered in the chats.

Nonetheless, through analysing the WhatsApp chats and other sources, we identified a range of challenges to index-linked testing for children. These are illustrated in the flow diagram to the right. Some challenges were recognised barriers to provision of many forms of HIV testing, such as stock-outs of HIV test kits, difficulties reaching clinics, and stigma around HIV. However, we also identified some unexpected challenges, such as indexes sending someone else to the clinic on their behalf, and a lack of familiarity with oral HIV testing, which resulted in low uptake. As index-linked HIV testing for children is used more widely it will be critical to find ways to ensure these challenges can be overcome.

The WhatsApp chats gave us valuable insight into the barriers and facilitators of index-linked HIV testing. It is important to consider newer technologies and social media alongside traditional sources of data to fully capture the complexity of implementation of public health interventions. By doing so, we can more effectively address barriers to delivery of interventions and ultimately improve health outcomes.

Read more about the B-GAP study and its findings in the following publications:

- Delivery of index-linked HIV testing for children: learnings from a qualitative process evaluation of the B-GAP study in Zimbabwe

- Comparison of index-linked HIV testing for children and adolescents in health facility and community settings in Zimbabwe: findings from the interventional B-GAP study

- Addressing the challenges and relational aspects of index-linked HIV testing for children and adolescents: insights from the B-GAP study in Zimbabwe

- Feasibility and Accuracy of HIV Testing of Children by Caregivers Using Oral Mucosal Transudate HIV Tests

Follow the Topic

-

BMC Infectious Diseases

This journal is an open access, peer-reviewed journal that considers articles on all aspects of the prevention, diagnosis and management of infectious and sexually transmitted diseases in humans, as well as related molecular genetics, pathophysiology, and epidemiology.

Related Collections

With Collections, you can get published faster and increase your visibility.

The rise of invasive fungal infections: diagnostics, antifungal stewardship, prophylaxis, and genetics

BMC Infectious Diseases is calling for submissions to our Collection on The rise of invasive fungal infections: diagnostics, antifungal stewardship, prophylaxis, and genetics.

In recent years, the incidence of invasive fungal infections (IFI) has shown a concerning upward trend, presenting a formidable challenge in clinical settings worldwide. This Collection aims to explore multidimensional aspects crucial for understanding and combating these infections. We invite submissions that explore a wide array of topics within the scope of IFI, including but not limited to:

- Diagnostics: advances in fungal diagnostics, including novel biomarkers, imaging modalities, and molecular techniques, are pivotal for timely and accurate identification of fungal pathogens

- Antifungal stewardship: the prudent use of antifungal agents to mitigate resistance and optimize patient outcomes, and strategies for stewardship (including surveillance, guidelines, and therapeutic drug monitoring)

- Antifungal prophylaxis: effective prophylactic measures in high-risk patient populations (examining prophylactic regimens, their efficacy, and impact on patient outcomes)

- Host and pathogen genetics: understanding the genetic factors influencing both host susceptibility and fungal virulence, and research on genetic markers, host-pathogen interactions, and implications for personalized treatment approaches

- Fungal genetics: insights into fungal genome characteristics, evolution, and mechanisms of resistance, and research exploring fungal genetic diversity, adaptation, and transmission dynamics

- Imaging: imaging technologies that contribute significantly to the diagnosis and management of invasive fungal infections, their clinical utility, and integration with diagnostic algorithms

This Collection aims to foster a dialogue among researchers, clinicians, and healthcare providers on the complexities surrounding IFI. This Collection supports and amplifies research related to SDG 3: Good Health & Well-being.

All manuscripts submitted to this journal, including those submitted to collections and special issues, are assessed in line with our editorial policies and the journal’s peer review process. Reviewers and editors are required to declare competing interests and can be excluded from the peer review process if a competing interest exists.

Publishing Model: Open Access

Deadline: Feb 28, 2026

Cutting-edge diagnostics for infectious diseases: emerging technologies and approaches

BMC Infectious Diseases invites submissions for a Collection on Cutting-edge diagnostics for infectious diseases.

The field of diagnostics for infectious diseases is rapidly evolving, driven by the need for timely and accurate detection methods. Traditional diagnostic techniques often fall short in terms of speed and sensitivity, highlighting a pressing need for innovative solutions. Recent advances in technologies such as molecular diagnostics, biosensors, and next-generation sequencing are paving the way for more efficient and reliable testing methodologies. These emerging approaches have the potential to revolutionize the identification of pathogens, enabling faster clinical decision-making and improving patient outcomes.

Addressing the challenges posed by infectious diseases is critical, particularly in an era marked by global health crises and the rise of antimicrobial resistance. The development and implementation of rapid diagnostic tools can facilitate timely interventions, ultimately reducing morbidity and mortality rates. As researchers and healthcare professionals work collaboratively, significant strides have been made in understanding the complexities of infectious diseases. This includes the adaptation of point-of-care testing technologies that bring laboratory capabilities closer to patients, thus enhancing the capacity for early diagnosis and treatment.

If current research trends continue, we may see transformative advancements that integrate artificial intelligence and machine learning into diagnostic processes. Such innovations could lead to the creation of smart diagnostics that not only detect infections with high accuracy but also provide real-time surveillance data. Future technologies may enable rapid identification of emerging pathogens, thus enhancing public health response strategies and mitigating outbreaks before they escalate.

- Advances in molecular diagnostics for infectious diseases

- Innovations in rapid diagnostic testing

- Applications of next-generation sequencing in pathogen detection

- Biosensors for real-time infectious disease monitoring

- Point-of-care testing technologies and their impact

This Collection supports and amplifies research related to SDG 3: Good Health and Well-being.

All manuscripts submitted to this journal, including those submitted to collections and special issues, are assessed in line with our editorial policies and the journal’s peer review process. Reviewers and editors are required to declare competing interests and can be excluded from the peer review process if a competing interest exists.

Publishing Model: Open Access

Deadline: Mar 15, 2026

Please sign in or register for FREE

If you are a registered user on Research Communities by Springer Nature, please sign in