What are the genomic mechanisms linking seeds, climate, and pollinators?

Published in Ecology & Evolution, Genetics & Genomics, and Plant Science

Seeds are the starting point of plant’s life, but they are also its most decisive bottleneck. Seed ability to delay germination, to respond to temperature cues, or to invest in embryo size determines not only whether a seedling will survive, but also which environment the adult plant will experience for the rest of its life. In seasonal environments, such as the Mediterranean, these early decisions can mean the difference between encountering favorable conditions or facing drought, heat, or mismatched interactions with pollinators.

Despite their central role, we still know surprisingly little about the genomic basis of adaptation in seed traits, particularly in wild, non-model plant species. Most genomic studies of seed traits have focused on crops or model systems, often with the goal of improving yield rather than understanding adaptation in nature. As a result, we lack a clear picture of how seed traits evolve in response to the complex combination of abiotic factors (e.g., climate) and biotic factors (e.g., pollinators) that shape natural populations.

In this study, we set out to explore how adaptation in seed traits is encoded in the genome, and whether the same genomic regions involved in seed trait variation are also linked to adaptation to local climate and pollinator communities.

Why Brassica incana?

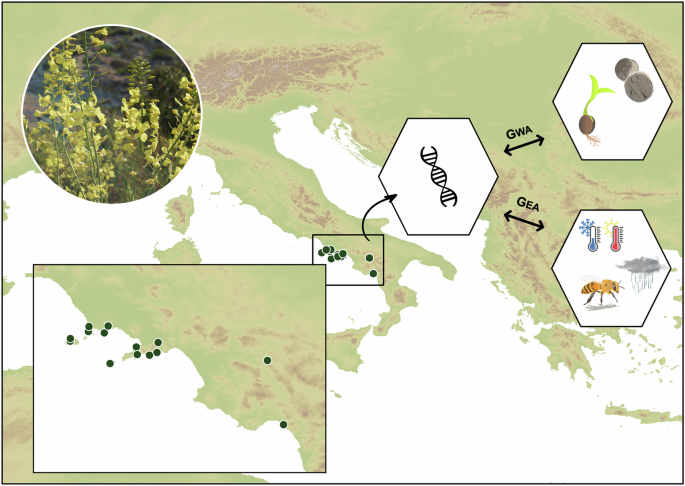

Our work focuses on Brassica incana, a wild perennial plant that grows on coastal cliffs in Southern Italy (Figure 1). This species is particularly well suited for studying local adaptation: its populations are highly fragmented, exposed to strong environmental heterogeneity, and subject to both harsh abiotic conditions and diverse pollinator communities. Previous studies in this system had already identified genomic signatures of adaptation to climate, soil, and pollinators, as well as strong population-level differences in seed germination responses.

What remained unclear was whether variation in seed traits themselves, traits that act before plants ever flower or interact with pollinators, also bears genomic signatures of adaptation, and how these signatures relate to the broader ecological context.

Figure 1. Brassica incana and its pollinating insect Bombus pascuorum in a wild population located in southern Italy

Measuring seeds across environments

To address this question, we combined ecological, phenotypic, and genomic data from 14 natural populations of B. incana. We focused on three broad categories of seed traits:

- Seed morphological traits, such as seed mass, relative embryo size, and seed coat thickness, which influence dispersal, persistence, and germination.

- Seed dormancy-related traits measured using germination responses of fresh seeds under different temperature regimes.

- Germination responses of non-dormant (after-ripened) seeds across a wide range of temperatures, including conditions outside those typically experienced in the local environment.

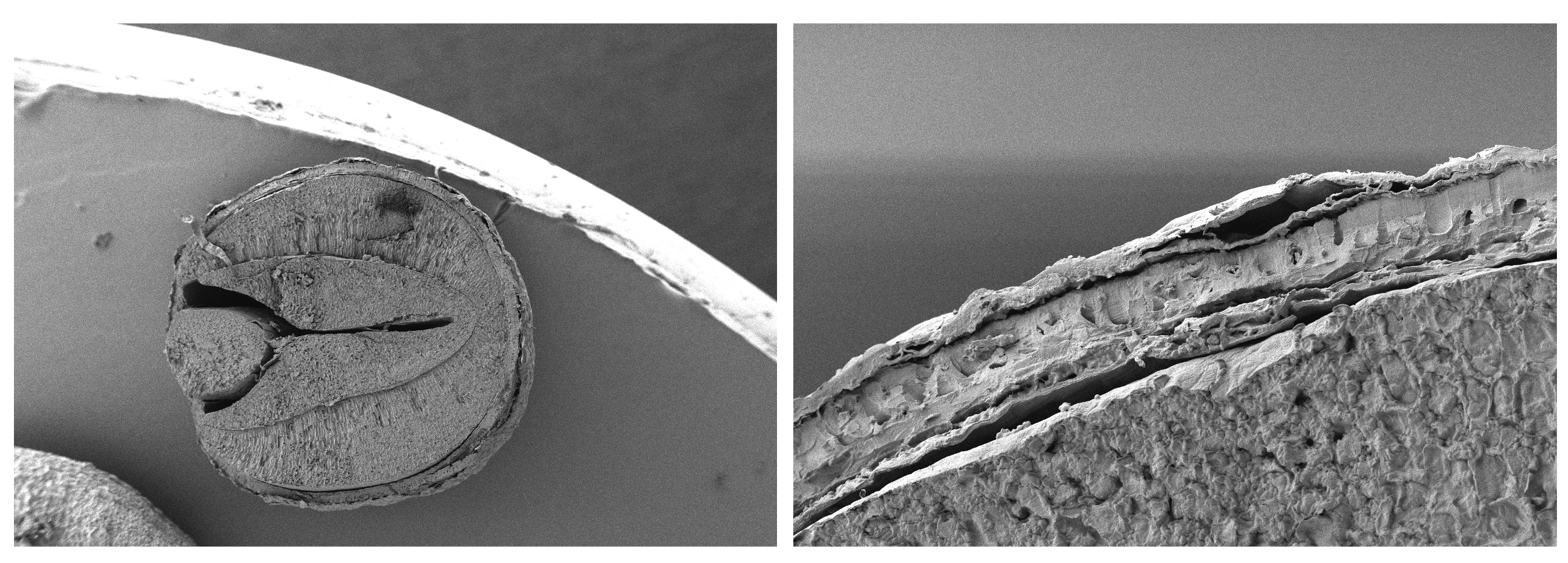

Measuring these traits required substantial experimental effort. Seed morphology was quantified using scanning electron microscopy, allowing us to visualize embryos and seed coats in remarkable detail (Figure 2). Germination experiments involved exposing thousands of seeds to controlled temperature regimes to capture how populations differ in their germination strategies.

Figure 2. Images obtained through scanning electron microscopy (SEM), used to calculate relative embryo size (i.e., embryo area to seed area ratio) and seed coat thickness in 14 wild populations of Brassica incana

Linking traits to genomes

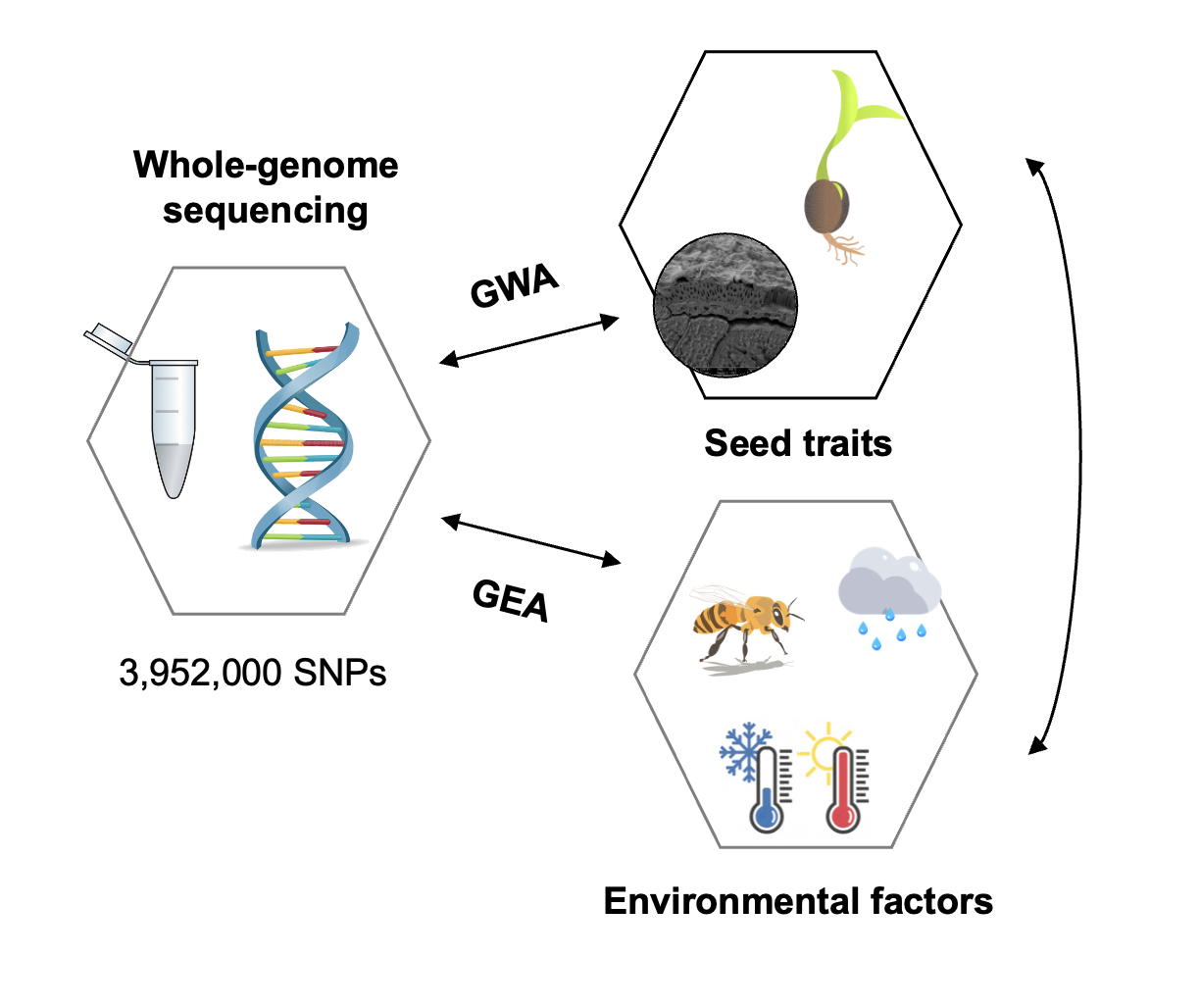

We then integrated these seed trait data with genome-wide pooled sequencing data using an ecological genomics framework. By combining genome-wide association analyses with scans for spatial genomic differentiation, we were able to identify genomic regions putatively involved in adaptation in seed traits. Importantly, we also tested whether candidate genes associated with seed traits overlapped with genes involved in adaptation to climate variables and pollinator community composition (Figure 3).

One of the most striking outcomes of this work was the complexity of the genetic architecture underlying seed trait adaptation. Rather than being governed by a single genetic model, seed traits showed a mixture of oligogenic and highly polygenic architectures, depending on their function.

Seed mass, a trait reflecting maternal investment, stood out as being shaped by relatively few genomic regions. In contrast, most traits related to germination timing and thermal responses were associated with many genomic regions of small effect, consistent with a polygenic model of adaptation.

Figure 3. Description of the ecological genomics approach combining genome-wide association (GWA)

based on seed traits (seed morphological traits and seed germination responses) and

genome-environment association (GEA) based on abiotic and biotic environmental

variables (climate and pollinator community composition).

Strong selection on dormancy-related traits

Another clear pattern was the strength of natural selection acting on seed traits, particularly those related to seed dormancy. Using a spatial genomic differentiation index, we detected strong signatures of selection for nearly all seed traits, with the strongest signals found for traits controlling whether seeds germinate under constant versus alternating temperatures.

This finding aligns with ecological theory and empirical evidence showing that dormancy is a key adaptive strategy in seasonal climates. In Mediterranean environments, avoiding germination during hot, dry summers can be critical for survival. Our results suggest that these ecological pressures leave a detectable imprint on the genome.

Interestingly, we also found signatures of selection for germination responses to extreme temperatures, both hotter and colder than those typically experienced locally. This raises the possibility that populations may already harbor genetic variation that could facilitate responses to future climatic extremes.

Seeds, climate, and pollinators: an unexpected overlap

Perhaps the most intriguing result emerged when we compared genomic regions associated with seed traits to those associated with adaptation to climate and pollinator communities. We found several candidate genes that were shared between seed traits and environmental variables, including precipitation and pollinator functional groups.

Some of these genes are known to play roles in seed development, dormancy regulation, temperature acclimation, or epigenetic control, suggesting plausible biological mechanisms linking early-life traits to environmental adaptation. Others are involved in pathways affecting traits expressed much later in the plant’s life cycle, such as floral characteristics relevant to pollinator attraction.

This overlap suggests that adaptation in seed traits may not be evolutionarily isolated from adaptation in adult traits. Instead, pleiotropy and genetic coupling may link early-life decisions to later interactions with the biotic environment. In other words, selection acting on pollinator-mediated traits could indirectly shape seed traits and vice versa.

Why does this matter?

Our study highlights the importance of considering early life stages when trying to understand plant adaptation to heterogeneous environments. Seeds are often overlooked because they are small, transient, and difficult to study, yet they represent a critical interface between genotype, environment, and life-history strategy.

In the context of climate change, this perspective is particularly relevant. Germination traits determine when and where plants establish, and thus shape the environments in which selection will act later in life. Understanding the genomic basis of these traits helps us better predict how wild plant populations may respond to shifting climates and altered biotic interactions.

At the same time, our results caution against overly simple views of adaptation. Seed traits are shaped by a complex interplay of polygenic adaptation, pleiotropy, and environmental heterogeneity, and their evolutionary trajectories are tightly linked to both abiotic and biotic factors.

Looking ahead

While our approach allowed us to identify putative genomic signatures of adaptation, future work will be essential to validate the functional roles of candidate genes and disentangle genetic effects from environmental influences. Common garden experiments, functional genomics, and studies across multiple years will help refine our understanding.

By integrating seed biology, genomics, and ecology, we hope this work contributes to a more complete picture of how plants adapt, starting from their very first stage of life.

Follow the Topic

-

Communications Biology

An open access journal from Nature Portfolio publishing high-quality research, reviews and commentary in all areas of the biological sciences, representing significant advances and bringing new biological insight to a specialized area of research.

Related Collections

With Collections, you can get published faster and increase your visibility.

Signalling Pathways of Innate Immunity

Publishing Model: Hybrid

Deadline: Feb 28, 2026

Forces in Cell Biology

Publishing Model: Open Access

Deadline: Apr 30, 2026

Please sign in or register for FREE

If you are a registered user on Research Communities by Springer Nature, please sign in