What happened when China randomly assigned people to farm rice or wheat

Published in Social Sciences, Agricultural & Food Science, and Behavioural Sciences & Psychology

It's easy to think of China as a unified culture, but recent studies have found evidence of large cultural differences within the country. One theory to explain these differences is that rice farming gave southern China a more interdependent culture than northern China, which farms wheat. But it is hard to pinpoint true causes because cultures and farms don't fit neatly into laboratories--until a recent natural experiment was uncovered.

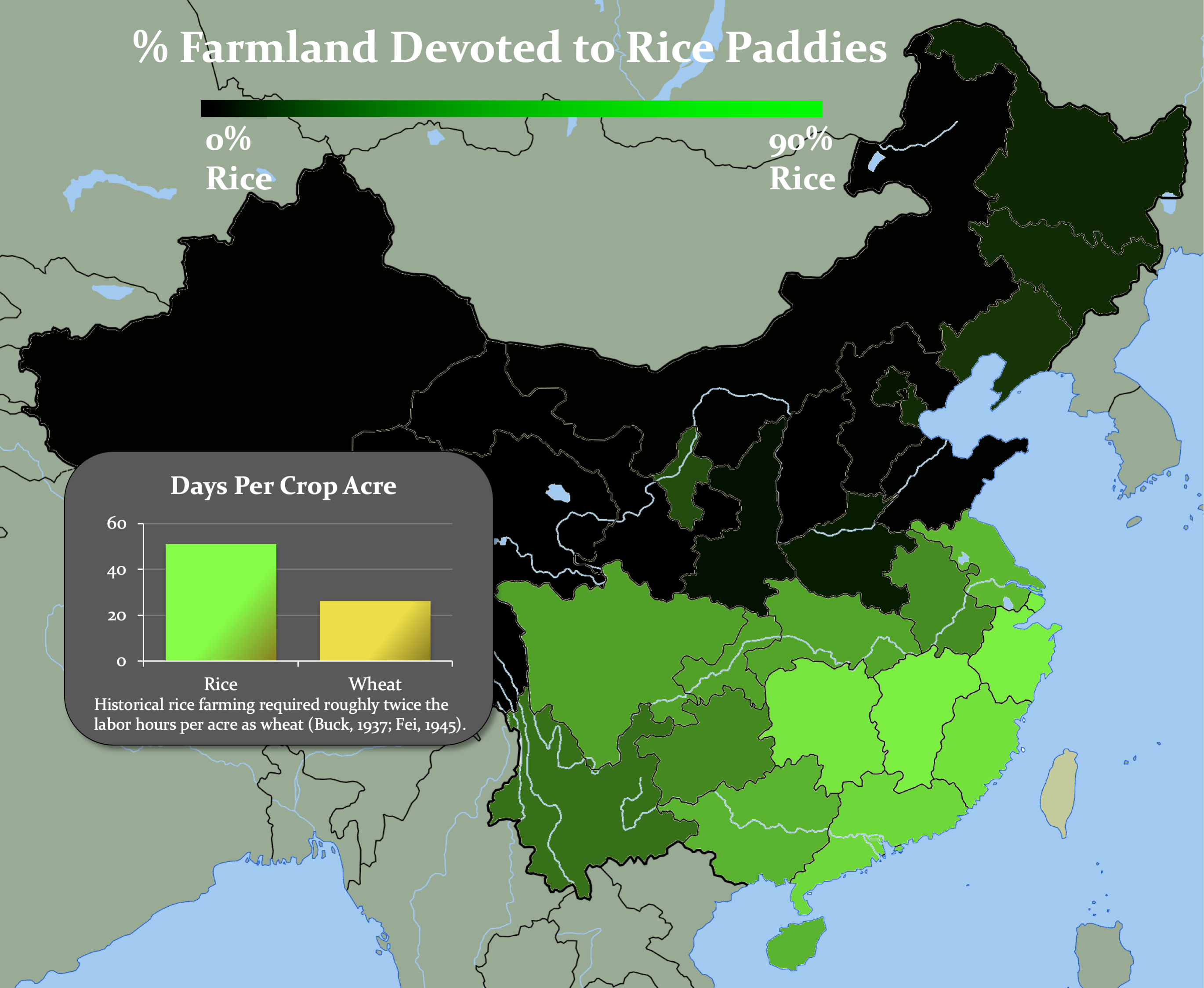

Why Rice Is So Different from Wheat

The rice theory is based on the process of farming rice and wheat. The idea is that differences in the process of farming influenced the culture.

One difference is irrigation. Paddy rice grows in standing water, so rice villages built irrigation systems to flood and drain their fields. Those systems lock farmers into a network they need to manage together. They need to coordinate when they flood their fields, who gets how much water, and how to maintain the channels.

Rice also required more labor than wheat. Anthropologists studying traditional villages in China found that rice took about twice the labor as wheat wheat. Farmers relied on other people to cope with these labor demands. Farmers would enlist neighbors and extended family to make it through periods of peak labor demands, like planting, transplanting, and harvesting.

The theory is that, over time, the need for coordination shaped rice-farming cultures to be more interdependent. In contrast, wheat farming required less coordination. The relative freedom of wheat farming allowed people to be more independent and relationships to be a bit looser.

A Question of Causality

One way to test this theory is to give psychological tests to people in northern and southern China. Several studies have found cultural differences in that fall onto the historical borders of rice and wheat farming. For example, southern China has lower divorce rates and stronger ties to friends over strangers than northern China.

People in interdependent cultures tend to emphasize fitting into the social environment, rather than disrupting it. Consistent with this theory, studies have found that people in southern China are less likely to move chairs out of the way in Starbucks and less likely to literally draw outside the lines in a creative drawing task. Rice cultures have tighter social norms and more committed social relationships whether comparing regions within China or countries around the world.

But these methods still make it hard to pin down causality. The gold standard in psychology is to invite people to a laboratory, randomly assign them to do one of two things, and then test them to see how they change. But we cannot randomly assign people to farm rice for a lifetime in the lab just to see what happens.

But it just so happened that China unintentionally did just that back in the 1950s. After World War II and China's civil war ended, the country had masses of soldiers who all of a sudden needed work. The country also had a growing population and many mouths to feed.

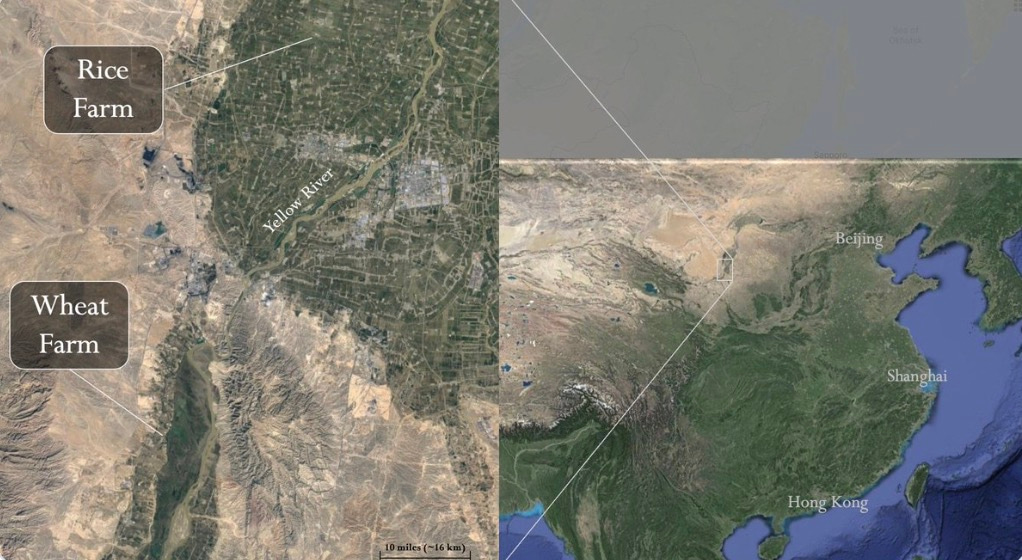

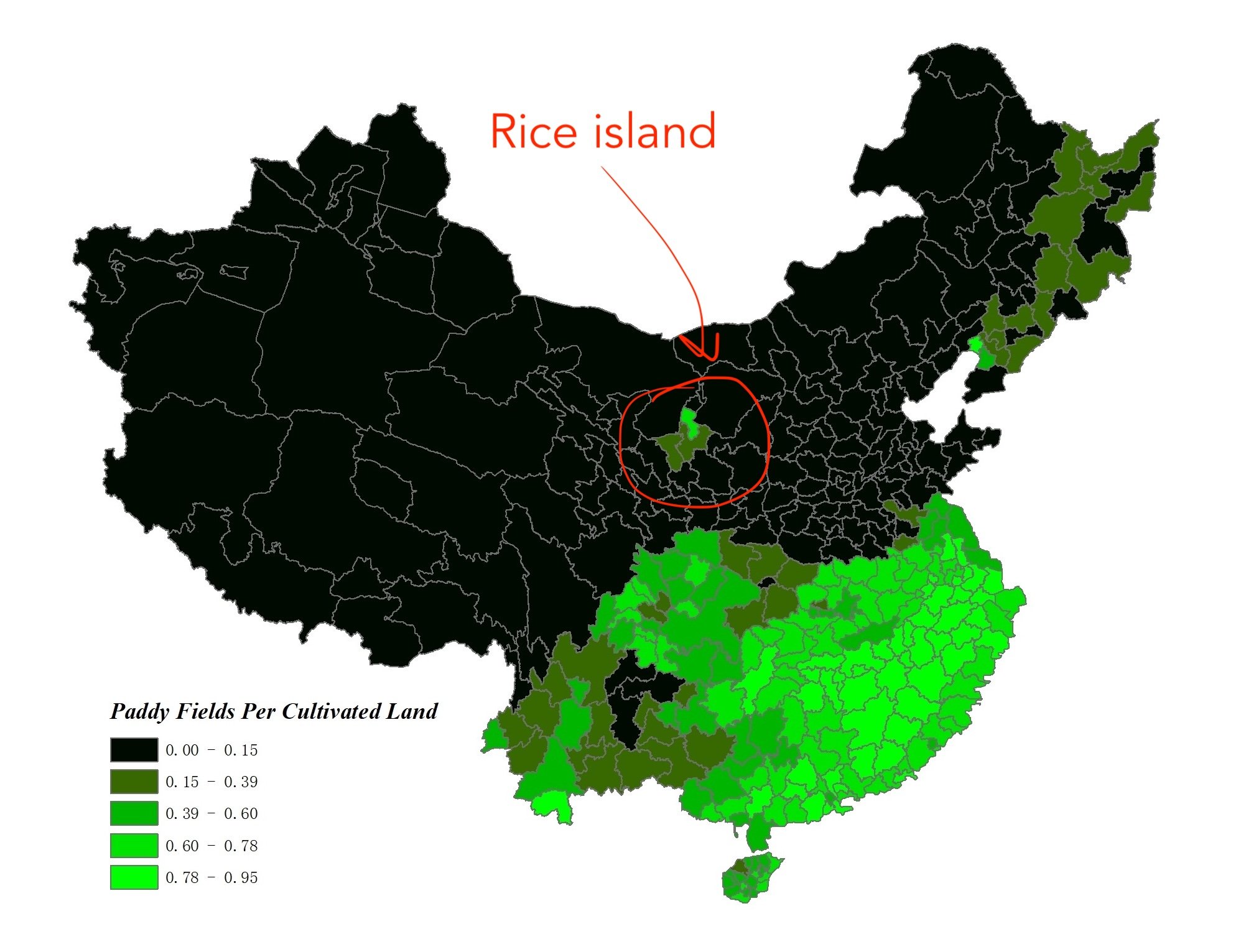

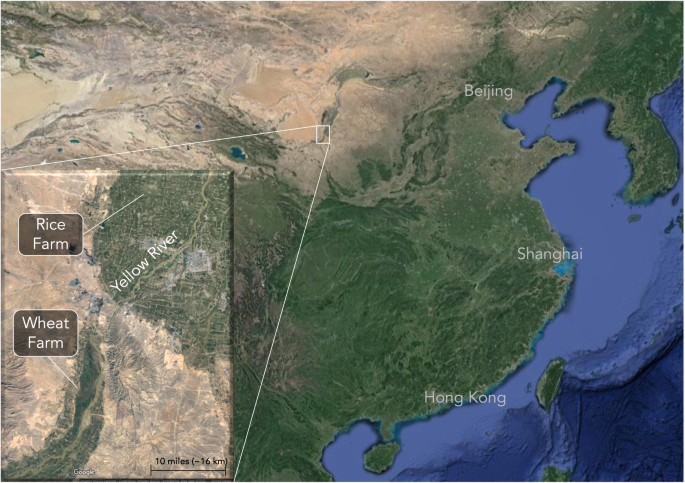

To address these problems, the government started creating state-run farms. They created new farmland in outlying areas and sent people to work. Two of those farms were in Ningxia Province, a remote corner of northwest China. One farm was rice, one wheat.

The two farms were 56 kilometers away from each other, about an hour down the road. That means they're virtually identical in terms of temperature, rainfall, latitude, and history. But one farms sits slightly above the nearby Yellow River, which made wheat more practical than irrigated rice farming.

Because this was 1950s China, there was essentially no option for personal preference. The government assigned people to these farms, regardless of their backgrounds or their parents. This was practical (but not intentional) random assignment.

It might make sense for the rice farm to select people from rice areas and the wheat farm to select people from wheat areas. But historical records from the farms show no evidence for selective recruitment based on people's skills. Even when an influx of workers from a rice-farming province came to the area, the government split them evenly between the rice and wheat farms.

Putting the Theory to the Test

With this backdrop of practical random assignment to rice and wheat, my collaborator and I set to work giving psychological tests to people on the two state farms. We used the same psychological tests that had shown differences between northern and southern China.

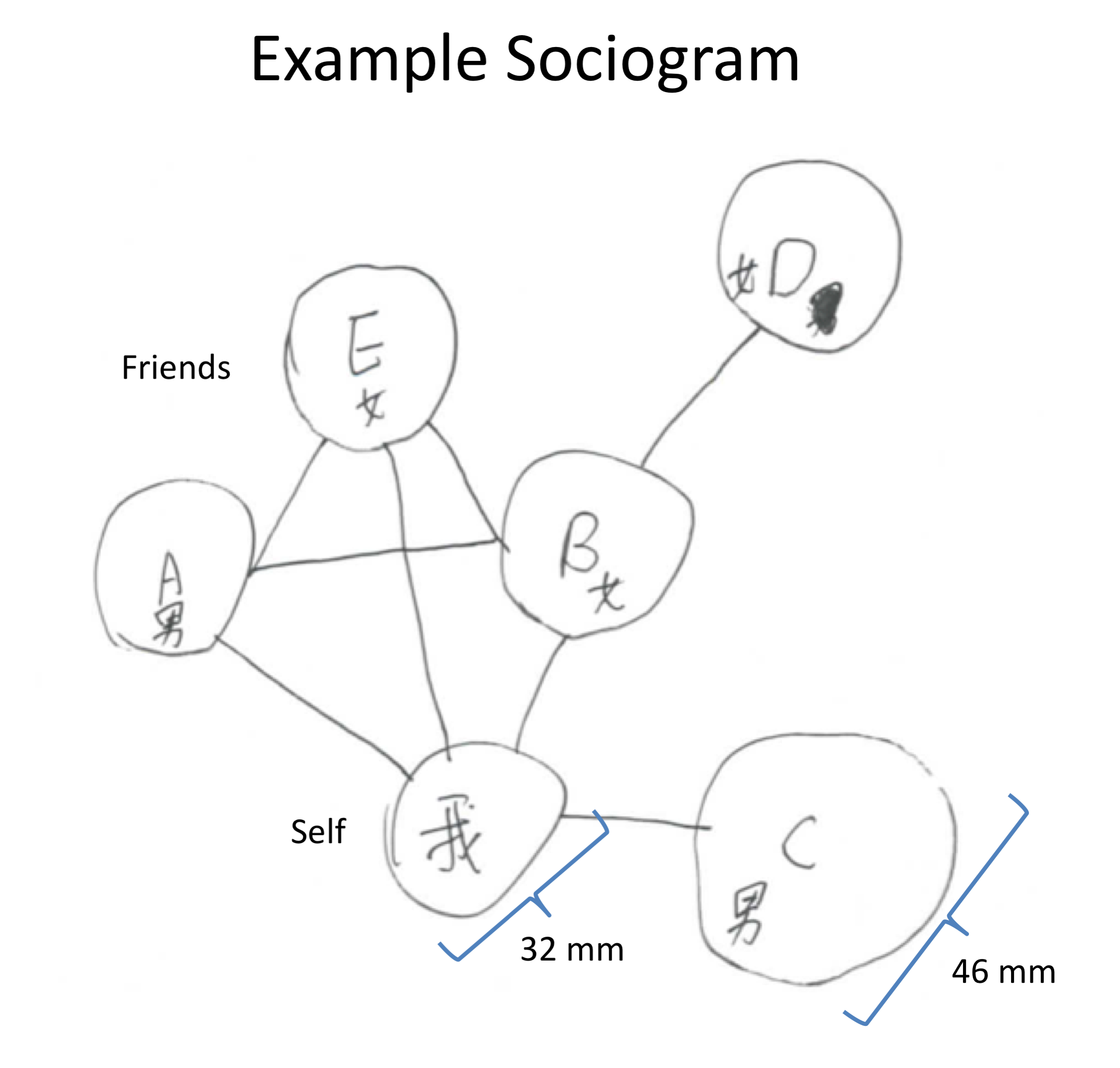

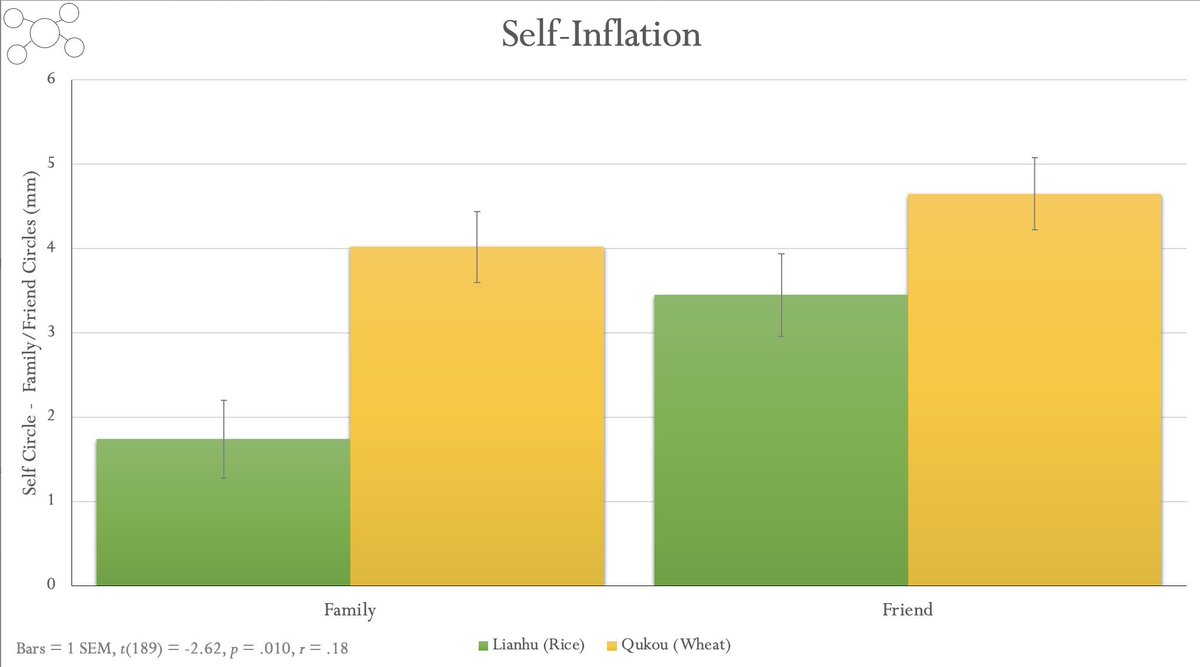

One test asked people to draw circles on a sheet of paper to represent themselves and their friends or family members. What we don't tell participants is that we later measure the size of the self to see if they draw the self larger than they draw their friends.

Previous research found that people in individualistic cultures like the US and the UK show more "self-inflation" than people in Japan. On the two farms, wheat farmers self-inflated more than the rice farmers.

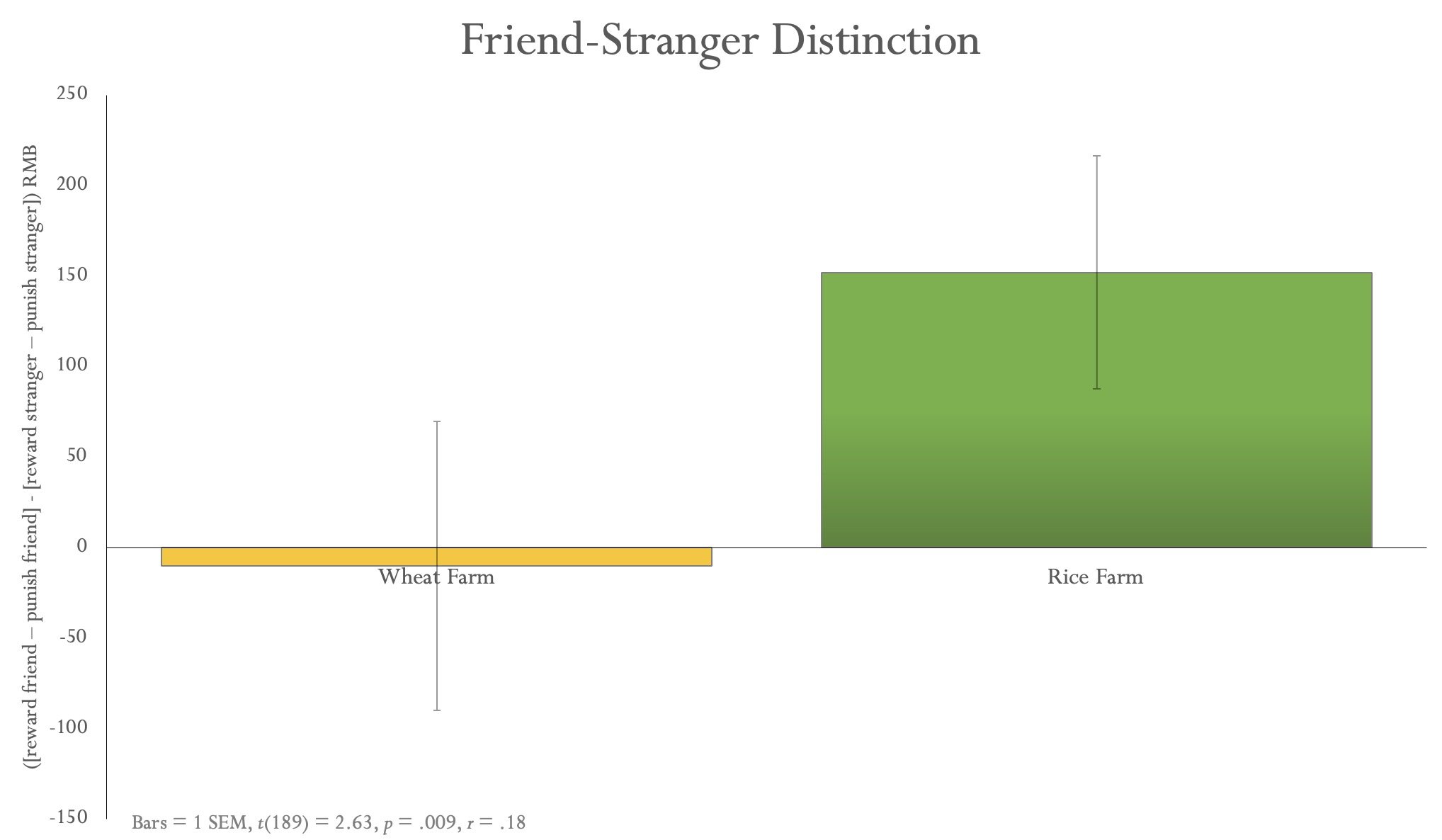

We also gave farmers a measure of the distinction between friends and strangers. In the task, farmers imagine learning that a friend or a stranger had been dishonest with them. Then they can punish the friend or stranger by magically deleting money from their bank account.

Previous research tested this with people in the US and in Singapore, a more interdependent culture. People in Singapore punished the stranger much more than the friend. But Americans treated the friend and stranger more similarly.

We found similar differences on the rice and wheat farms. Rice farmers showed a larger friend-stranger distinction than wheat farmers.

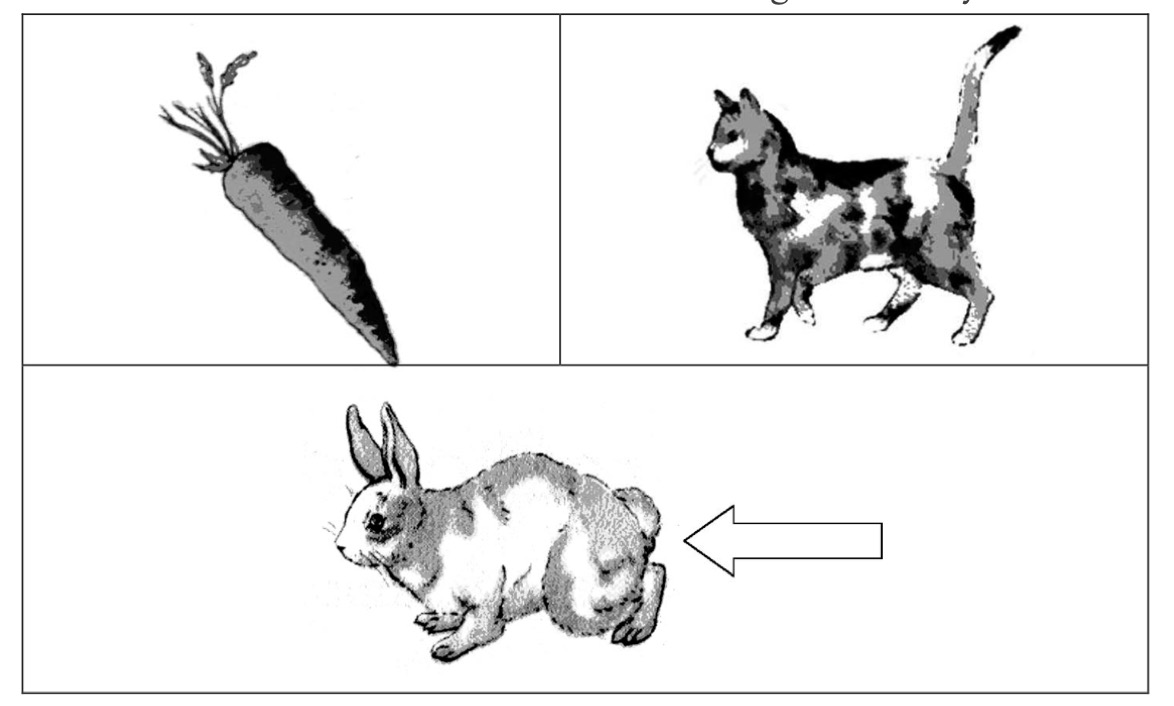

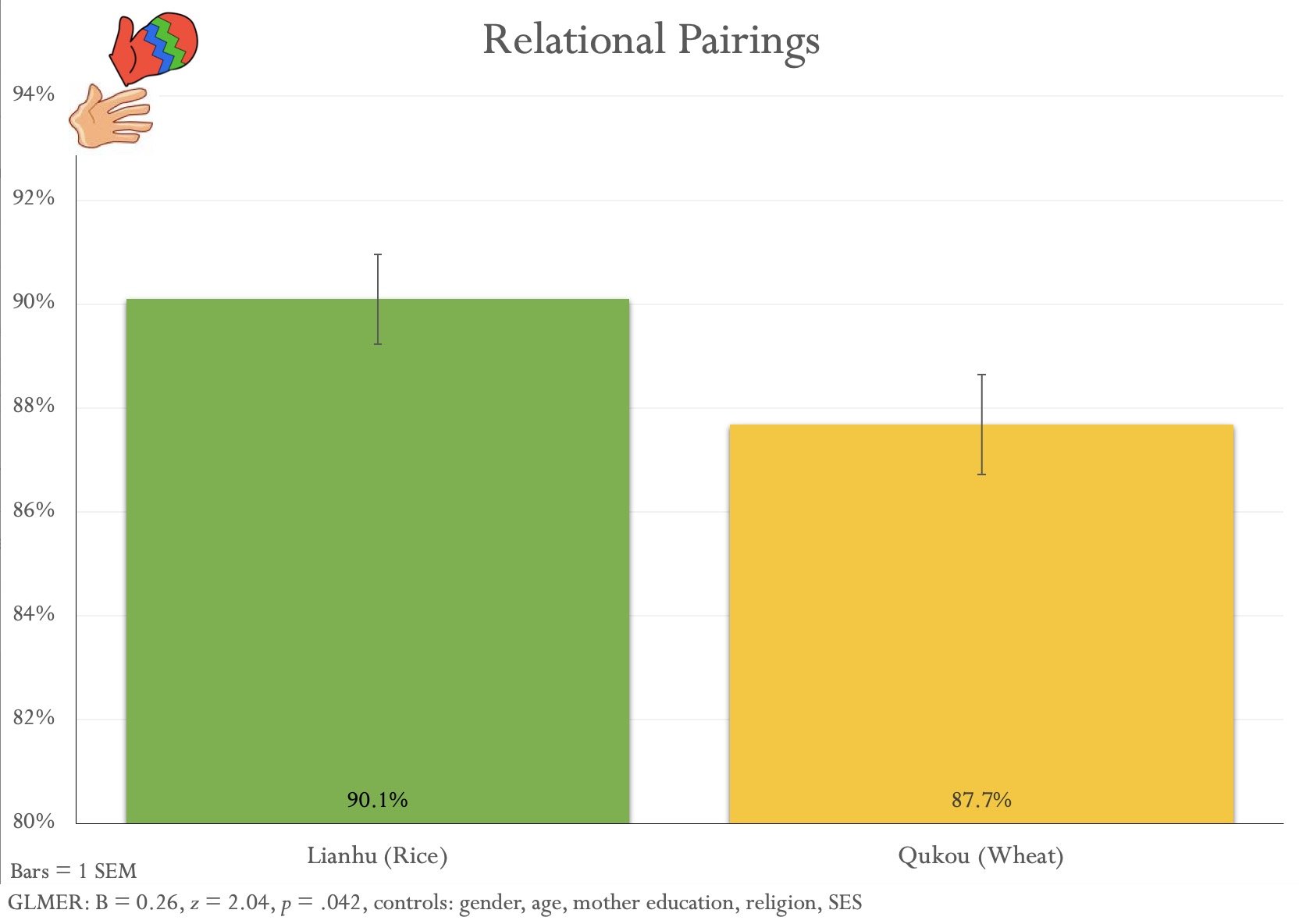

We also gave farmers a measure of cultural thought style. They saw series of three items and chose two to categorize together, such as cat, carrot, and rabbit.

Cat and rabbit are an abstract pairing based on categories. The rabbit and carrot are a holistic pairing based on a functional relationship. Previous studies have found that people in interdependent cultures like China and India tend to choose pairings based on relationships, whereas people in individualistic cultures like the US and Sweden more often choose pairings based on abstract categories. On the two farms, rice farmers chose more relational pairings than wheat farmers.

A 70-Year Dose of Rice Farming

Seventy years is a lifetime, but it's still a short time compared to southern China's thousands of years of rice farming. The differences between these two farms showed evidence for the effect of rice farming, but the differences were smaller than in previous studies comparing southern and northern China as a whole. This suggests that 70 years is enough to influence culture, but it falls short of the experience of thousands of years of accumulated history.

This rice farm was also different from southern China in an important way. It is an isolated rice island in a sea of wheat. Most farms in northwest China plant wheat and other dryland crops.

That probably dilutes the rice culture in northwest China. When surrounded by other rice-farming areas, the culture can get reinforced through shared norms and institutions. But when the rice farm is surrounded by wheat-farming areas, the strong coordination norms of rice probably get weakened when people interact with people who've inherited the lessons of wheat farming.

These two state farms offer a rare natural experiment to test the effects of rice and wheat farming. The psychology that sprung up on these two farms suggests that farming shapes culture. It could also hold clues into differences between East Asia, which was built mostly on rice, and the West, which was built mostly on crops like wheat and rye.

Follow the Topic

-

Nature Communications

An open access, multidisciplinary journal dedicated to publishing high-quality research in all areas of the biological, health, physical, chemical and Earth sciences.

Ask the Editor – Collective decision-making

Got a question for the editor about Experimental Psychology and Social Psychology? Ask it here!

Continue reading announcementRelated Collections

With Collections, you can get published faster and increase your visibility.

Women's Health

Publishing Model: Hybrid

Deadline: Ongoing

Advances in neurodegenerative diseases

Publishing Model: Hybrid

Deadline: Mar 24, 2026

Please sign in or register for FREE

If you are a registered user on Research Communities by Springer Nature, please sign in

You can read the full text of the paper (for free) here: https://www.nature.com/articles/s41467-024-44770-w

Thanks to@Danila Medvedev for helpful edits on the draft of the paper.