What happens to fisheries when coral reefs bleach?

Published in Ecology & Evolution

A marine heatwave that turned coral reefs into seaweed fields has made reef fisheries less predictable and more productive, impacting small-scale fishers over 20 years later. In our new paper, we document how a mass coral bleaching changed the composition of fish communities, and how this led an increase in the amount of fish caught by artisanal fishers.

Our research was the result of a collaboration between nine ecologists and fisheries scientists working across three countries for over 20 years. I want to explain why teamwork and sharing monitoring data were critical to the success of our study.

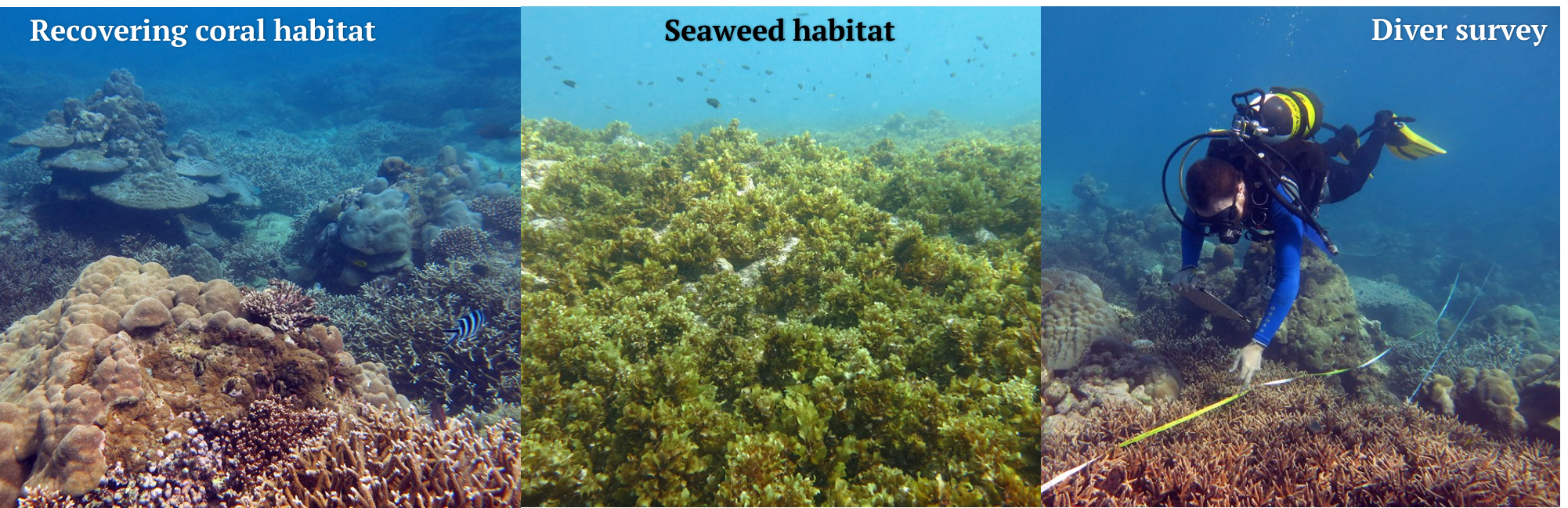

When coral reefs are exposed to heat stress and corals bleach, complex and diverse underwater seascapes can turn into flat rubble habitats that are easily overgrown with seaweeds. Coral reefs also provide food and employment for billions of people - by reducing fish habitat, bleaching is expected to lower fisheries' productivity and so impact food security in the tropics. But fisheries landing data do not exist for most reefs, meaning we have very little empirical evidence of how climate change will affect tropical food security.

The link between coral bleaching and reef fisheries is complex. Corals can recover, and fish can be slow to respond to habitat changes. The seaweeds that replace corals, though providing a less complex habitat, can be highly productive and support several species of fish important to artisanal fishers.

We work in Seychelles, an island group in the Indian Ocean where, in 1998, a mass bleaching event caused >90% of corals in the inner island group to die. Since 1994, our team have collaborated with Seychelles Fishing Authority (SFA) and other organisations to collect an underwater time-series that has been highly influential for understanding climate impacts on coral reefs. Seychelles is also a nation of fishers, and SFA have collected data on small-scale catches from coral reefs for over 25 years.

The datasets are exceptional: from 1994 to 2016, SFA spent almost 6,000 days talking to fishermen to catalogue over 40,000 catches, while scuba divers spent 1,000's of hours underwater counting over 60,000 reef fish. These data were a unique opportunity to study long-term climate impacts, and all that was left was interpretation: we turned noisy information into ecological patterns with R code and statistical models.

We found that catches increased or were stable in the 20 years following bleaching, which coincided with higher numbers of herbivores on the reef. However, overgrowth by seaweeds at some reefs led to greater spatial variation in habitat types and, as fish species started to associate with either seaweed or coral habitats, the variability in catch sizes also increased. Our findings suggest that bleached reefs can still provide food, but their fisheries are less predictable, and may become dominated by seaweed-feeding rabbitfishes.

This work was only possible because our collaboration allowed us to combine fishery-dependent (catches) with fishery-independent (underwater) information spanning over 20 years. By drawing on the expertise of ecologists, statisticians, and fisheries scientists, we were able to present several lines of evidence that linked complex ecosystem changes to fishers' catches.

Coral reefs will continue to change as the planet warms - such collaborative and interdisciplinary research will be critical if we are to detect and adapt to future climate impacts.

Follow the Topic

-

Nature Ecology & Evolution

This journal is interested in the full spectrum of ecological and evolutionary biology, encompassing approaches at the molecular, organismal, population, community and ecosystem levels, as well as relevant parts of the social sciences.

Related Collections

With Collections, you can get published faster and increase your visibility.

Biodiversity and ecosystem functioning of global peatlands

Publishing Model: Hybrid

Deadline: Jul 27, 2026

Understanding species redistributions under global climate change

Publishing Model: Hybrid

Deadline: Jun 30, 2026

Please sign in or register for FREE

If you are a registered user on Research Communities by Springer Nature, please sign in