What I Learned When I Stopped Studying College Students

Published in Social Sciences, Agricultural & Food Science, and Behavioural Sciences & Psychology

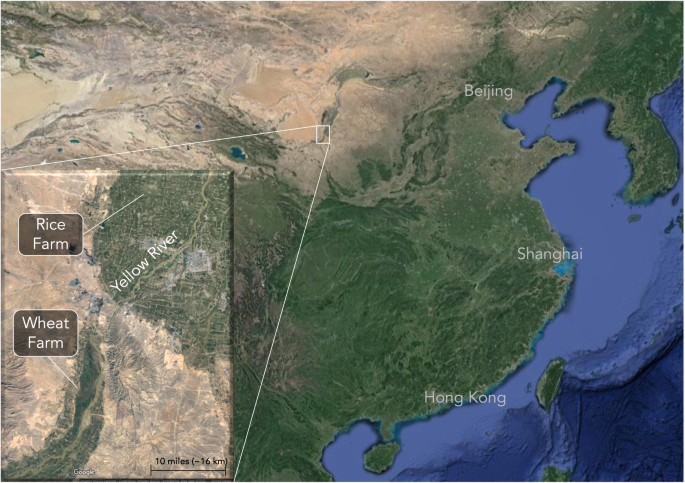

Recently, I published a study testing people on two state farms in northwest China--one rice, one wheat. I wanted to research these two farms because they provided the cleanest natural experiment I have ever seen on rice versus wheat farming. Because the government effectively randomly assigned people to farm rice or wheat, they give unique insight into whether rice farming really shapes human culture.

But testing people on the farms taught me lessons about human psychology that I hadn't anticipated. I think that's because this was by far the least "WEIRD" sample I have ever tested--the acronym researchers created to describe societies where most studies come from, Western Educated Industrialized Rich and Democratic societies.

Like most psychologists, I had mostly tested undergraduate students in my studies. Perhaps I did a little better than average because 80% of psychology samples come from WEIRD cultures, and I often test people in non-Western cultures. But I was still testing mostly students.

So when I used my same methods with farmers in this remote part of China, I was doing something my teachers in grad school had ever trained me to do. And I wasn't prepared for the lessons it taught me.

Are Friends a Bourgeoisie Concept?

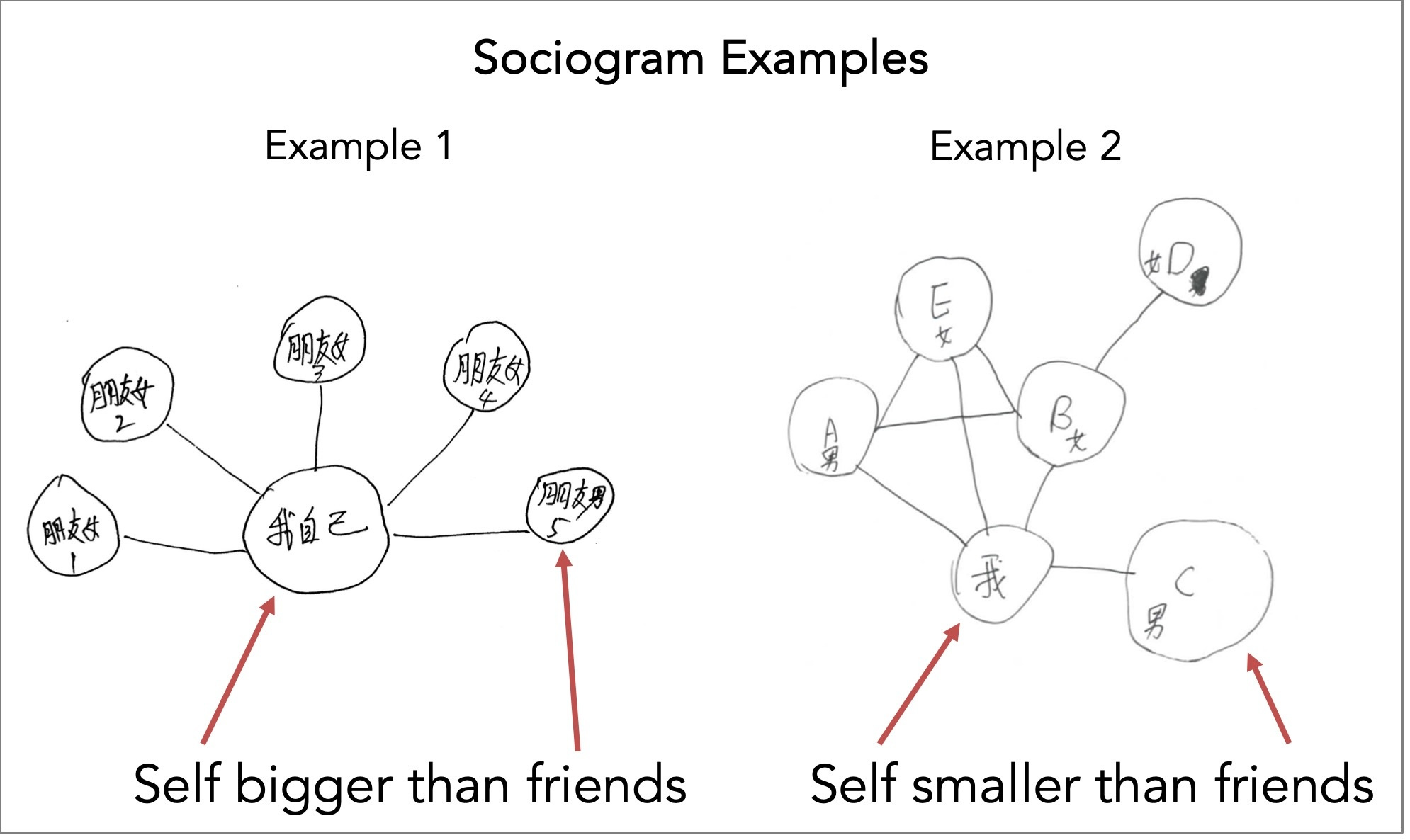

One test I used with the farms was the sociogram task. In the task, we ask people to draw circles to represent themselves and their friends.

Our goal (which we don't tell participants) is to see whether they draw themselves bigger than they draw their friends. Previous research has found that people in individualistic cultures like the US and UK tend to draw themselves bigger than they draw their friends. In Japan, people draw themselves about the same size as they draw their friends.

I had used this tasks with hundreds of college students before--even high school students. So I took the same task to the farms.

Soon after we started, one of the farmers appeared stumped. He looked at the paper and said, "pengyou...pengyou...," repeating the word for "friend." We realized that "friend" was not an obvious category for farmers in rural China.

Instead, more relevant categories were family members, strangers, neighbors, and work team members. (The farms are divided into work teams.)

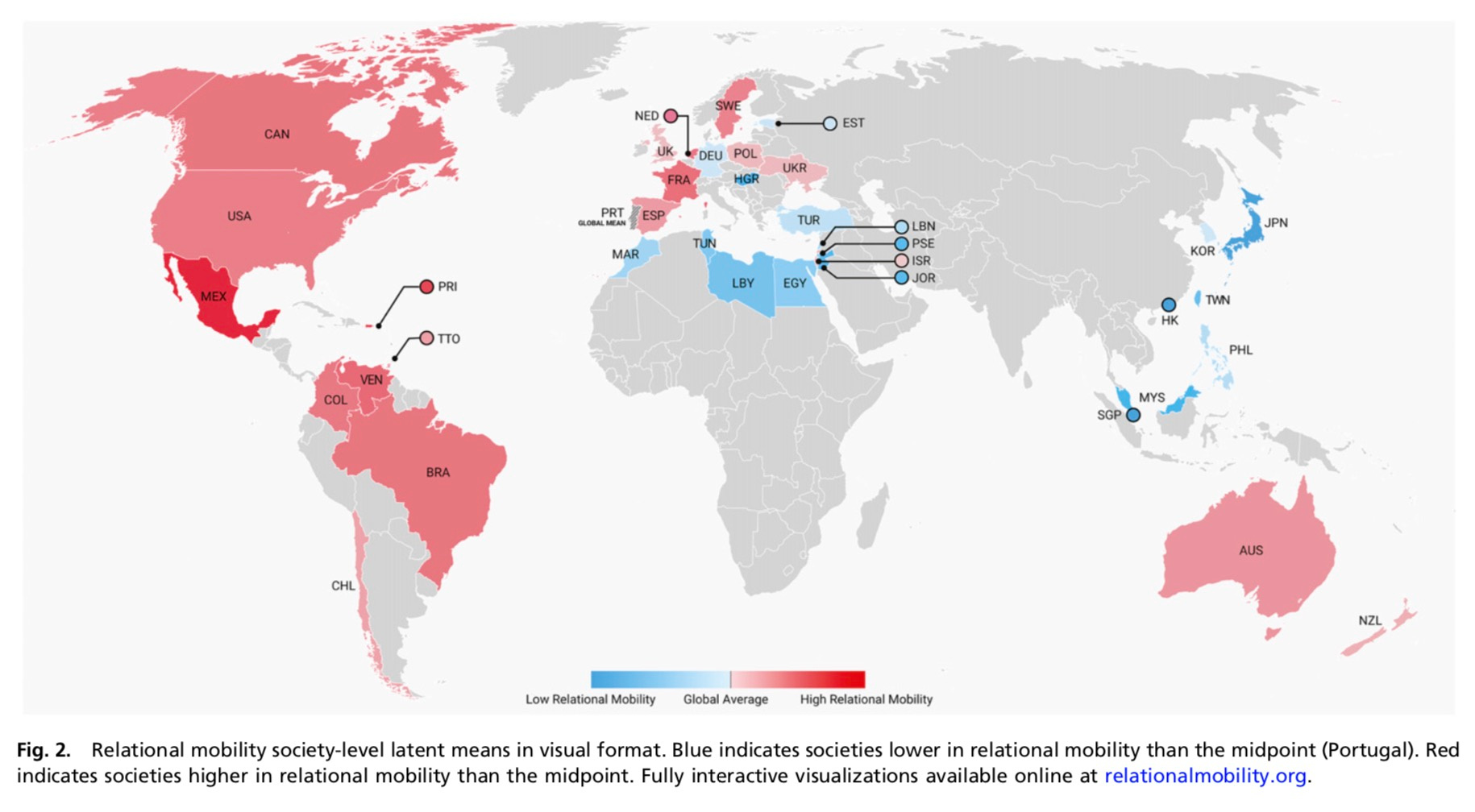

The key insight for me was that friendship often involves choice. Designating friends means dividing the social world into the people you like and the people you don't like. But that sort of choice is much more common in Western cultures than non-Western cultures, according to a study of relationships across 39 cultures.

Adapting Measures to the Local Context

So we pivoted. We created a family sociogram by asking farmers to draw family members rather than friends. And we never saw that stumped response again.

In the end, after we got all the data back, the family sociogram revealed larger differences than the friend sociogram. I suspect that's because the farmers could relate more to the family sociogram, which made the task more relatable.

The lesson on friendship stuck with me as much as the lesson about rice versus wheat farming. Friends seemed to me as natural a part of social life as parents and grandkids. But the farms made me realize that friendship is perhaps a bourgeoisie concept--one built on the luxuries of choice, mobility, and freedom. And those luxuries probably don't describe the majority of humans throughout history.

Follow the Topic

-

Nature Communications

An open access, multidisciplinary journal dedicated to publishing high-quality research in all areas of the biological, health, physical, chemical and Earth sciences.

Ask the Editor – Collective decision-making

Got a question for the editor about Experimental Psychology and Social Psychology? Ask it here!

Continue reading announcementRelated Collections

With Collections, you can get published faster and increase your visibility.

Women's Health

Publishing Model: Hybrid

Deadline: Ongoing

Advances in neurodegenerative diseases

Publishing Model: Hybrid

Deadline: Mar 24, 2026

Please sign in or register for FREE

If you are a registered user on Research Communities by Springer Nature, please sign in

Thanks to Xiawei Dong, without whom this study would not have happened!

The paper is a free download available here: https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=4823719