When Machines Paint, Humans Still Carry the Load: Reimagining Automation’s Purpose

Published in Social Sciences, Computational Sciences, and Philosophy & Religion

The Promise Was Liberation

When Artificial Intelligence first began to emerge from laboratories into public consciousness, it carried not just the promise of technological advancement, but something far deeper: a vision of human liberation. We imagined machines taking over the most grueling, repetitive, and dangerous tasks—not because they were faster or cheaper, but because they could finally free us from the cycle of labor that had defined much of human history. For centuries, the working class was bound by physical toil, their bodies worn down by factory floors, fields, mines, and assembly lines. The dream was simple yet radical: if machines could handle the mechanics, humans could reclaim time, energy, and spirit for what truly matters—creativity, connection, care, contemplation, and meaning. This vision wasn’t merely about efficiency; it was about dignity, about redefining progress not as output, but as well-being.

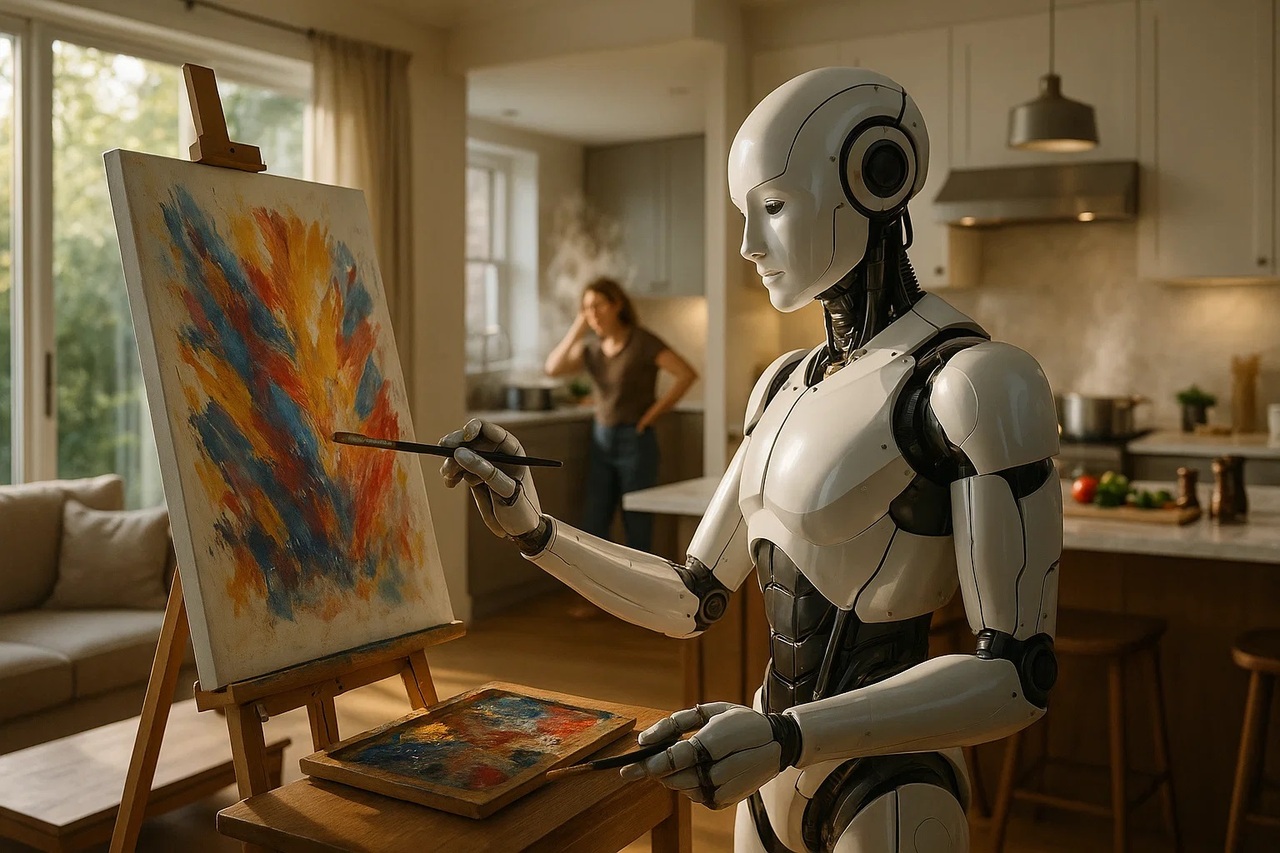

And yet, decades later, we find ourselves staring at a quiet, unsettling inversion. AI now excels at generating art, music, and stories—works once considered the pinnacle of human expression—while millions of people around the world continue to perform jobs that demand relentless physical endurance, emotional resilience, and mental focus under conditions that often feel dehumanizing. The irony is impossible to ignore. We have automated the creative spark—the very thing that defines our uniqueness—while leaving behind the bodywork that should have been the first target of automation. Why? Because we chose to. And that choice reveals not a technical limitation, but a moral one.

The Pattern Repeats

This is not the first time humanity has made such a mistake. History is littered with tools that were supposed to liberate us, only to become instruments of control, distraction, or waste. The printing press, for instance, was invented to spread knowledge but later fueled propaganda and mass media manipulation. The automobile, designed to connect people, enabled urban sprawl, pollution, and car dependency. Even the internet—initially intended for open communication—transformed into a machine for surveillance, attention extraction, and misinformation.

Now, AI stands at a similar crossroads, and once again we are repeating the same error: treating the tool as the solution, regardless of context. We have fallen into the trap of the “law of the instrument,” Abraham Maslow’s famous observation that if all you have is a hammer, everything looks like a nail. In this era, the hammer is AI, and so we apply it everywhere—even when the task is not a nail at all.

Consider the example of a company using GPT-4 to draft routine internal updates. The output may be technically correct, but it is sterile: devoid of tone, empathy, or nuance. Yet management celebrates it as “efficiency.” Or think of an AI chatbot replacing a human agent for basic inquiries. The system works—until the customer expresses frustration. At that point, the system collapses, offering no compassion, no flexibility, only scripted responses. Or look at brands using image-generation models like Stable Diffusion to create “unique” visuals for campaigns. These images are marketed as “digital art,” despite the fact that the training data included millions of copyrighted works by real artists, often without their consent or compensation.

These are not isolated incidents. They represent a cultural shift. We no longer ask whether a task needs AI—we simply ask whether we can use AI. And because we can, we do.

The Hidden Costs

Every time we run a large language model to rewrite a paragraph, we expend vast resources: thousands of kilowatt-hours of electricity, millions of lines of code, gigabytes of data, and human attention in the form of prompts, edits, and oversight. And what do we get in return? A slightly rephrased sentence, a marginally more engaging headline. The question must be asked: is this worth the environmental cost, the carbon footprint, or the mental fatigue of constantly refining machine output? The answer is no.

What we have created is a productivity paradox. We feel productive because we have used AI, but in reality, we are becoming less thoughtful, less authentic, and less connected. We have traded deep thinking for rapid generation, reflection for repetition, and in the process, we have convinced ourselves that this hollow cycle represents progress.

The Human Cost of Industrial Logic

The story of industrialization was never truly about machines replacing humans—it was about humans becoming interchangeable parts in a system designed to maximize output. In the early stages, factory owners dreamed of fully automated production lines, where every task could be broken down into discrete, mechanical operations. But they quickly realized that not all tasks could be mechanized, particularly those requiring dexterity, judgment, adaptability, or emotional intelligence. Instead of redesigning machines to bridge these gaps, they made a pivotal decision: they inserted human workers into the process.

This was not innovation; it was compromise. And it came at a terrible cost. Workers were no longer seen as people but as cogs in a vast mechanism, their bodies and minds reduced to inputs in a system that valued speed over safety, efficiency over dignity. The result was a wave of physical injuries, chronic stress, mental fatigue, social alienation, and psychological disconnection. These were not side effects; they were built into the model itself.

Even today, decades after the introduction of ergonomics, automation, and workplace reforms, many of these issues persist. The underlying logic remains unchanged: humans are still treated as tools to fill the gaps left by machines. We may have improved chairs, adjusted workstations, and added breaks, but we have not questioned whether the system itself should be redesigned.

Now, with AI and robotics advancing rapidly, we stand at a new turning point. For the first time, we have the technological means to close the loop—not just automating repetitive motions, but also addressing the cognitive and emotional labor that has long been outsourced to people. The real challenge is not technical but ethical. Can we use intelligent mechanization not to control humans, but to free them from degrading labor? Can we build systems where robots don’t just replace human effort but restore human value?

A Call for Recalibration

What we need is not more AI, but better judgment. It is time to stop treating AI as a magic bullet and start treating it as a tool that must be earned, justified, and constrained. Before deploying any model, we should ask: Is this problem complex enough to require intelligence? Could a simpler solution—a policy, a workflow, or a human touch—do it better? Who benefits, and who loses? If the answer to these questions does not justify the use of AI, then we should not use it.

We must stop rewarding companies for adopting AI indiscriminately and begin rewarding them for achieving real impact: improved safety, equity, and well-being. We should consider taxing the misuse of AI in trivial tasks while funding automation in fields such as agriculture, construction, and caregiving—domains where physical relief and human welfare would be genuinely enhanced. At the same time, we must protect human creativity, not merely as a product but as a process—something sacred, irreplaceable, and worth defending.

The future we should strive toward is not one where machines write poetry while humans stack boxes. It is a future where machines lift the weight so that humans can create, care, and live with dignity.

The Real Measure of Progress

The essential question is not what AI can do, but what we choose to let it do. That choice, ultimately, belongs to us. It is a choice between convenience and conscience, between spectacle and substance, between efficiency and humanity. We have built powerful tools, but we have not yet learned how to wield them wisely. The real measure of progress is not how fast a machine can generate text, but how much it frees us to be fully, freely, and authentically human.

Please sign in or register for FREE

If you are a registered user on Research Communities by Springer Nature, please sign in