Why an ancient farming method is changing in the Himalayas

Published in Social Sciences, Sustainability, and Agricultural & Food Science

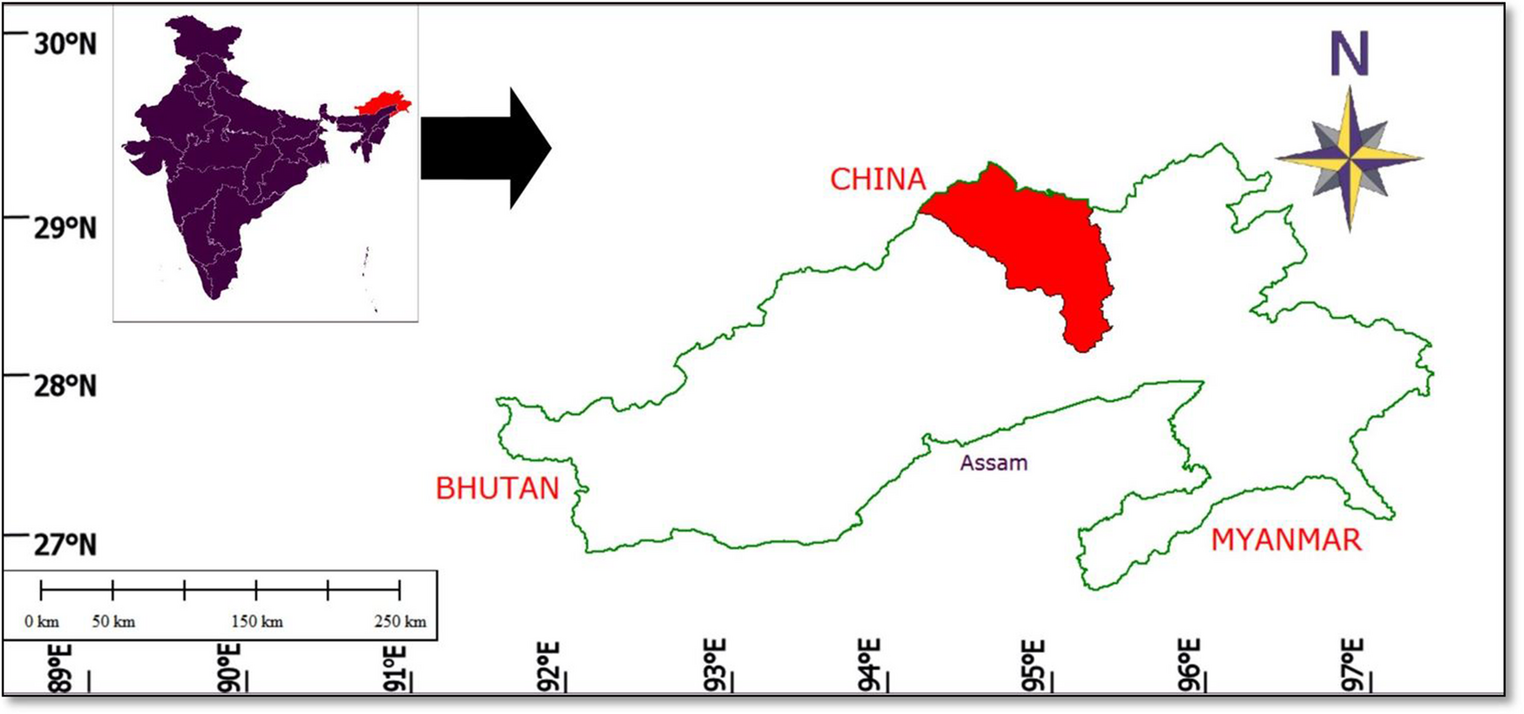

Across the tropical highlands of the world, this form of traditional landuse is known by many names. But what remains common is that this agricultural system becomes inseparable from the social and economic lives of its practitioners. Swidden cultivation, also known as ‘shifting cultivation’ is a farming method that has not just sustained mountain communities for thousands of years, but remains deeply woven into their culture, traditions, festivals and even their identities. In the Asian highlands of northeast India, this traditional practice is undergoing significant changes, and our study from Bomdo village in Arunachal Pradesh, India, offers a detailed glimpse into how and why this is happening. These insights, we feel go far beyond this remote Himalayan village, helping us to understand such changes in other parts of the world where it is practiced.

.jpg)

What exactly is Swidden? It's more than just 'slash and burn'

Often misunderstood and unfairly criticized as 'slash and burn', swidden agriculture is a sophisticated system of rotational farming. The Adi people in the village of Bomdo, would carefully select a patch of forest on the steep mountainsides. They'd clear the vegetation, let it dry, then burn it in a controlled fire. The ash would fertilize the soil, and for two years, they'd grow rice, millets, vegetables, and dozens of other crops in the same field. Then they would walk away and let the forest grow back in these ‘fallows’. For the next 10-15 years, the forest would slowly heal itself, accumulating nutrients and rebuilding the soil. When the time was right, the cycle would begin again. And all around this cycle and the seasonal cycle of activities like clearing, burning, fencing, sowing, weeding, harvesting were the different festivals and the cultural life of the Adi.

This system is far from ‘unproductive’ or ‘detrimental to the environment’ as some critics have claimed. In fact, research shows that when practiced with appropriate fallow periods and traditional knowledge, swidden can be sustainable, eco-friendly, especially in nutrient-poor, high-rainfall highland areas. It even plays a role in conserving biodiversity and can be carbon-neutral over time, as regrowing vegetation sequesters the carbon released during burning. Yet across Asia, governments have spent decades trying to eliminate this practice, convinced it was destroying forests.

.jpg)

Bomdo – Keeping the tradition alive

For this remote mountain village in Arunachal Pradesh, located along the mighty Siang river (originating from the Tsangpo and becoming the Brahmaputra later), swidden has long been a central part of life and tied to cultural identity, animistic beliefs, and community rituals of the Adi tribe. The traditional institution of the kebang, made up of village elders play a central role in dispute resolution, natural resource management and even the timing of swidden agricultural activities. The success of the crops often hinges on the kebang's decisions regarding the agricultural calendar, ensuring the entire community works together on tasks like fencing or burning within a specific timeframe.

Within Bomdo, land for swidden is divided among families, with customary rights passed down from father to son. Interestingly, if a family has more land than they can cultivate, they often permit other villagers to use it, fostering a sense of communal cooperation. Villagers rotate cultivation over a ‘fallow period’ of 10-15 year cycle, ensuring adequate time for the land to recover.

Winds of Change – The WRC factor

Even in remote Bomdo, changes were underway. We used satellite imagery dating back till 1990 along with extensive interviews to go back in time and understand these changes. Results showed a significant decline in swidden cultivation over the decades. From an average of 135 hectares between 1990-2000, swidden land shrank to 80.9 hectares between 2010-2023.

What's driving this transformation? Much of the swidden areas have been replaced by "wet rice terraces" (WRC). These permanent agricultural fields, focusing solely on rice, have become increasingly popular. By 2013, a staggering 94.7% of households in Bomdo owned at least one WRC plot.

This shift isn't accidental. It's largely propelled by state policies that actively promote terraced farming through subsidies and infrastructure development. Modern tools and increased local knowledge have also made creating these terraces easier and more affordable. There’s even a growing preference among the younger generation for terracing, as it’s less physically demanding than swidden.

On paper, this sounds like progress. Rice terraces are certainly easier to farm once they're built, and they provide a more predictable harvest. But something profound is being lost in translation.

The costs of ‘development’

The shift to rice terraces brings benefits, but also unexpected costs. While swidden produced a remarkable harvest of diversity - rice, millet, vegetables, medicinal plants, and dozens of varieties of each, rice terraces produce just one thing: rice.

This matters more than you might think. When your food comes from 50 different plants, a bad year for one crop doesn't mean disaster. When it comes from just one, you're vulnerable. The nutritional implications are significant too since traditional swidden diets are diverse and well-balanced.

There's also the question of land ownership. Swidden fields belonged to families but were managed collectively by the community. Rice terraces, by contrast, can be bought and sold as private property. This difference between stewarding land and owning may seem subtle but changes everything about how people relate to their environment.

Finally, as rice terraces create individually owned, permanent plots that operate independently of community scheduling, the kebang's agricultural oversight and guidance has become largely irrelevant. Coinciding with the new village institution of Panchayati Raj, the wise elders of the kebang have been sidelined.

Embrace change, value the past

The adaptability and intelligence of the Adi people demonstrates how they survive in such challenging conditions. Today, most families in Bomdo practice both swidden and terrace farming, finding the sweet spot between tradition and modernity. It's a practical approach that recognizes both systems have value. The story of Bomdo village demonstrates that agricultural modernization in highland regions isn't a simple, linear path and cannot be left to one-dimensional agricultural policies that aims to homogenize. While subsidies and less physically demanding farming methods like WRC is attractive, traditional swidden agriculture remains irreplaceable when it comes to food security, cultural continuity, ecological sustainability and benefits to biodiversity.

But the deeper question remains: In a world facing climate change and biodiversity loss, what can we learn from farming systems that sustained communities for thousands of years? The Adi recognize its importance, but this realization needs to be realized in official policies too. The most important need is for policies that don't blindly push for ‘modernization’ but thoughtfully balance it with support for traditional practices and local governance systems. The future of these unique highlands and the vibrant cultures that call them home depends on finding a way to harmonize change with tradition, ensuring resilience for both people and the planet.

As one village leader told us, "We are not against change. But we want to choose our own path between the old ways and the new ones."

Follow the Topic

-

Human Ecology

This is an Interdisciplinary Journal focuses on the complex systems of interaction between humans and their environment.

What are SDG Topics?

An introduction to Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) Topics and their role in highlighting sustainable development research.

Continue reading announcementRelated Collections

With Collections, you can get published faster and increase your visibility.

The First Pandemic: Transformative Disaster or Footnote in History?

This collection aims to gather innovative studies on the preconditions and impact of the First Plague Pandemic at a regional level, written by interdisciplinary, multi-author teams. By focusing on regional rather than global approaches, the collection will feature individual highlights that together provide a nuanced view of this historical event across three continents and about two centuries. We particularly welcome studies that offer new data or reinterpretations of existing sources from various disciplines, such as cultural history, funerary archaeology, paleoclimatology, paleogenetics, numismatics, archaeozoology, palynology, medical history, papyrology, physical anthropology, and philology. Authors are free to select their focus, ranging from entire subcontinents to specific towns, and from the entire duration of the First Pandemic to particular outbreaks.

Questions that the papers can address include:

- What is the current state of research in the region, and what gaps exist?

- What was the temporal extent of the FP in the respective region? What are the patterns in the frequency and magnitude of outbreaks?

- What climatic, environmental, ecological, social, cultural, and political factors contributed to the spread of the plague? What variables and contexts might have promoted or hindered its dissemination?

- What were the effects of the plague on demographic, ecological, social, economic, cultural, and political levels? How can these effects be identified?

- What factors contributed to the vulnerability or resilience of societies? What differences in their ability to cope can be observed within these societies?

- What are the differences between the historical and scientific methods and their implications? How practical are the various approaches for observing general trends or local variations? Can different data be combined into a single cohesive picture, or do discrepancies remain?

Publishing Model: Hybrid

Deadline: Ongoing

Please sign in or register for FREE

If you are a registered user on Research Communities by Springer Nature, please sign in