Why projection direction matters in pediatric full-spine radiography

Published in Healthcare & Nursing, Physics, and Paediatrics, Reproductive Medicine & Geriatrics

Why projection direction matters in pediatric full-spine radiography

Full-spine radiography is an essential imaging examination for children with scoliosis.

In daily clinical practice, these patients undergo repeated examinations over many years to monitor spinal curvature and treatment response. Each individual examination delivers a relatively low radiation dose, but the cumulative exposure over time is not negligible—especially for radiosensitive organs in growing children.

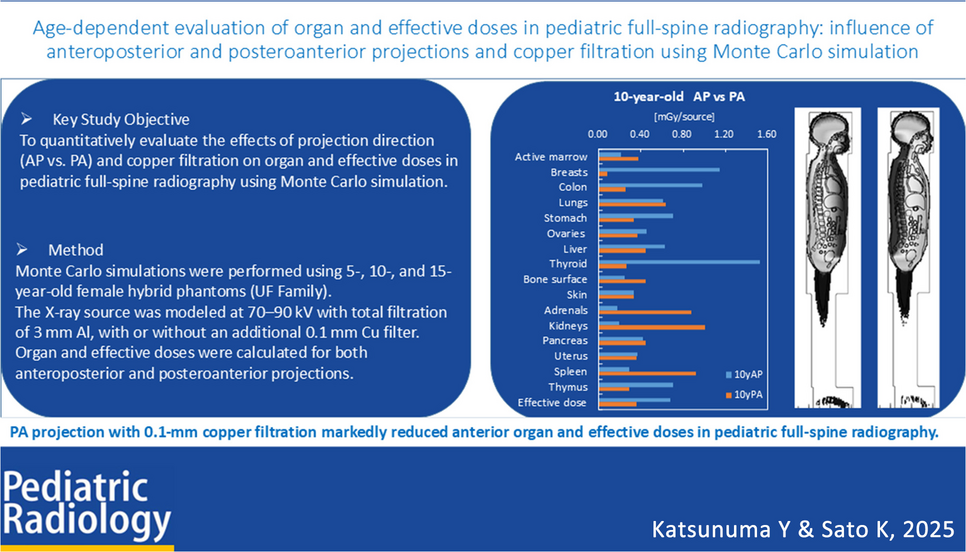

Radiologic technologists and radiologists are therefore constantly balancing diagnostic image quality against radiation protection. One widely recommended strategy is the use of posteroanterior (PA) projection instead of anteroposterior (AP) projection, as PA imaging is thought to reduce radiation dose to anterior organs such as the breast and thyroid. However, while this recommendation is often cited, quantitative evidence—particularly in children of different ages—remains surprisingly limited.

This gap between recommendation and detailed evidence was the starting point of our study.

From clinical intuition to a research question

In our department, pediatric scoliosis patients are followed carefully, sometimes from early childhood into adolescence. During these years, imaging protocols are often standardized for workflow and reproducibility, yet subtle differences—such as projection direction—can have a meaningful impact on organ dose.

Clinically, PA projection is generally preferred when feasible, but questions remained unanswered.

How large is the dose reduction for specific organs?

Does the benefit change with patient age and body size?

Are all organs equally protected by PA imaging?

These questions are difficult to answer using measurements alone, particularly in pediatric patients. This led us to consider a simulation-based approach.

Why Monte Carlo simulation?

Direct dose measurements in children are ethically and practically limited. Monte Carlo simulation offers a powerful alternative, allowing us to estimate organ doses under controlled and reproducible conditions.

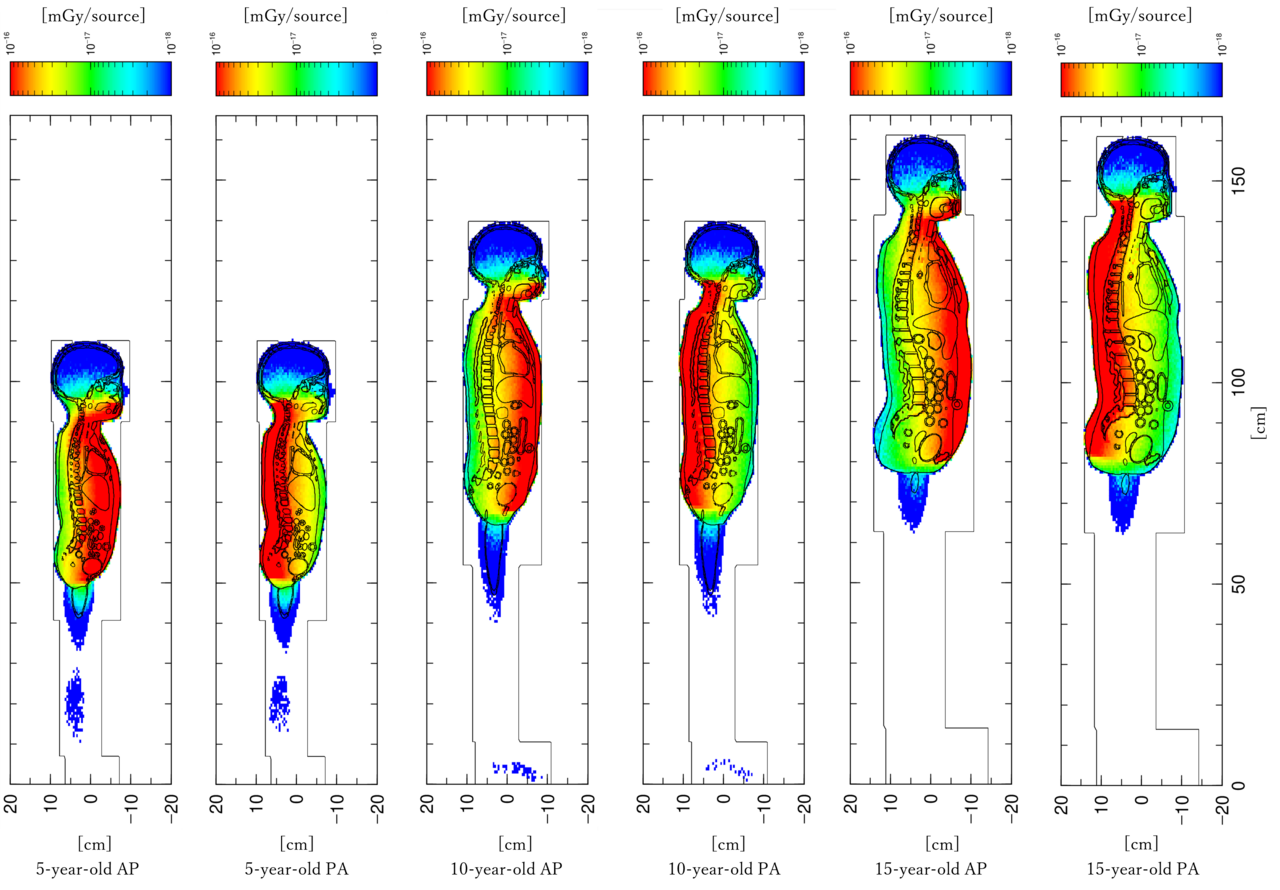

For this study, we used age-specific hybrid computational phantoms representing pediatric patients at different developmental stages. These phantoms incorporate realistic anatomy and organ positioning, enabling us to examine how X-ray attenuation and dose distribution change with growth.

Rather than focusing on absolute dose values, we chose to evaluate the AP/PA dose ratio for each organ. This relative comparison allowed us to isolate the effect of projection direction while minimizing the influence of other factors such as tube output or filtration.

This decision—simple in appearance—was a crucial methodological choice. It helped us focus on what truly matters for protocol optimization in clinical practice.

What surprised us in the results

The most striking finding was the magnitude of dose reduction for anterior organs.

For the breast and thyroid, PA projection led to a dramatic decrease in absorbed dose, particularly in older children and adolescents. As body thickness increases with age, the shielding effect of posterior tissues becomes more pronounced, amplifying the benefit of PA imaging.

At the same time, not all organs behaved in the same way.

For deeper or posteriorly located organs, such as the spinal cord or abdominal organs, the difference between AP and PA projection was smaller, and in some cases negligible.

These findings reinforced an important concept: projection direction does not uniformly affect all organs. Understanding this nuance is essential when designing or justifying imaging protocols.

Connecting physics and clinical practice

To better interpret our results, we also analyzed percentage depth dose (PDD) curves in soft tissue. This allowed us to link organ depth to dose behavior in a more intuitive way.

By comparing organ positions within the body to PDD characteristics, we could explain why certain organs benefited more from PA projection than others. This physical interpretation helped bridge the gap between simulation results and practical understanding.

For us, this was one of the most satisfying aspects of the study—seeing how radiation physics, anatomy, and clinical imaging come together in a coherent story.

Why this matters beyond numbers

While our study is computational in nature, its motivation is deeply clinical.

Clear, quantitative evidence helps radiologic technologists explain protocol choices to colleagues, referring physicians, and even patients’ families. Being able to say why a certain projection is preferred—and for whom—adds confidence and transparency to daily practice.

Moreover, pediatric imaging requires particular care. Small improvements in dose optimization can translate into meaningful long-term benefits when examinations are repeated over many years.

Looking ahead

This study is not the final answer.

Future work could include additional age groups, comparisons with image quality, or validation using physical dosimetry where feasible. We also hope that our approach encourages further discussion about protocol optimization tailored to pediatric patients rather than relying solely on adult-based assumptions.

Final thoughts

Behind every technical paper lies a series of clinical questions, methodological decisions, and interpretative challenges. This study began with a simple, practical concern—projection direction—and grew into a detailed exploration of pediatric dose behavior.

We hope that sharing the story behind the paper helps others reflect on their own imaging practices and inspires continued efforts toward safer, more thoughtful pediatric radiology.

Follow the Topic

-

Pediatric Radiology

This journal informs its readers of new findings and progress in all areas of pediatric imaging and in related fields.

Related Collections

With Collections, you can get published faster and increase your visibility.

Career development and professionalism in pediatric radiology

Publishing Model: Hybrid

Deadline: Ongoing

Musculoskeletal Ultrasound

Publishing Model: Hybrid

Deadline: Ongoing

Please sign in or register for FREE

If you are a registered user on Research Communities by Springer Nature, please sign in