Why the strangely colored pond? The beginning of research on mine drainage

Published in Earth & Environment, Economics, and Law, Politics & International Studies

When looking to buy vacant land in 2021 I (Jeremy) saw on Zillow a nicely situated property offered at a low price, prompting me to visit it. There I found the reason for the low price. It wasn’t so much that the property had been the site of a coal surface mine--casual observers would have seen few traces of mining. What gave me pause was the contaminated water seeping from the property’s hillside and flowing into a pond with strange multi-colored hues.

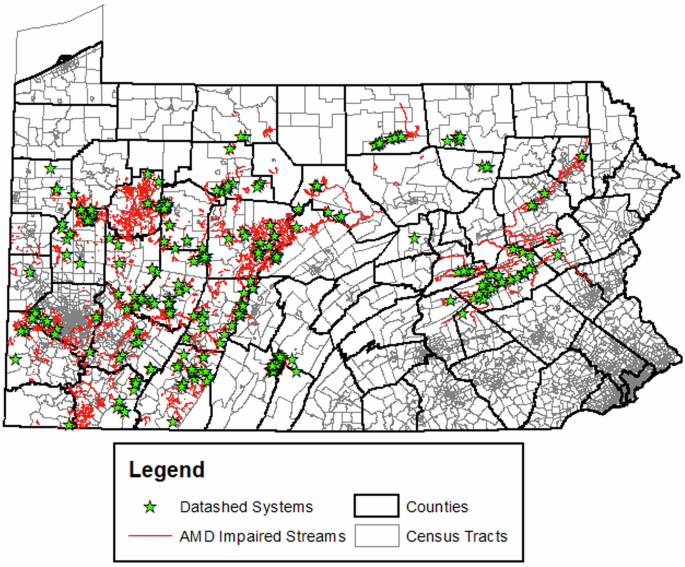

It was easy to imagine the downstream consequences of the discharge. I wouldn’t have wanted my kids to play in a stream with such water nor would I have expected to catch fish there. Fortunately, the discharge did not flow directly into the nearby stream but through a series of ponds, with the water of each successive pond clearer than the prior one. About a mile below the discharge was a stream known for its beauty and trout fishing. No doubt this series of treatment ponds helped protect that stream that was a source of pride for the community. The first-hand exposure to the mine discharge spurred many thoughts and questions. How well are such treatment systems working in general? How much do they cost? Do many discharges remain untreated, harming what is downstream? Who is affected by this type of water pollution? These became the questions addressed in our paper.

Originally, I (Katie) was drawn to this project because I’m a product of rural Western Pennsylvania, growing up on the Clarion River throughout my childhood weekends. I was very cognizant of the scale of mining and legacy environmental risks associated with it, however, I hadn’t extrapolated “downstream” until we modeled the drainage of abandoned mines. The more I’ve thought about improving water quality through this project, the more I’ve reflected on my time on the Clarion. When I was younger, I could find catfish, crayfish, bluegill, carp, and salamanders on the banks and from the dock, but there were many species that I didn’t see, though I was too young to realize they were missing. It was also well known that you didn’t try to drink the river water.

I distinctly remember a summer in the late 2000’s when I looked over the side of our boat to a shocking sight: freshwater jellyfish! I had never seen these peach blossom jellyfish, which require clean water in order to thrive, indicating improving water quality. Two decades later, my daughters can see mussels, river otters, ducks, and bald eagles calling the Clarion River home, indicating a healthier waterway and more diverse ecosystem.

In the beginning of our project, we hosted a stakeholder’s conference for abandoned mine drainage at the University of Pittsburgh. It was fascinating to hear about the boots-on-the-ground efforts from local watershed groups, economic development commissions, and grant writing organizations. They provided us with thoughtful initiatives, creative solutions, and intriguing success stories. One group in particular who stood out to us was the local conservancy groups for Johnstown, PA. They spoke about the increased tourism and local support for restoring the Conemaugh River. The restoration has helped spur recreation, festivals, and other economic activity in the region.

Our first-hand engagement with the issue gave us the energy to overcome data and conceptual challenges to answering our research questions. The work involved much data wrangling, including stream network data neither of us had used before. But it is easy to face such obstacles when the questions are so intriguing and the answers so important for the health of waterways and the communities that might enjoy them.

We were also thankful that at least we had data needed to answer the questions, thanks to the work of local watershed associations, the Pennsylvania Department of Environmental Protection, and Stream Restoration Incorporated. Our analysis would not have been possible without their work to monitor treatment systems, test the quality of water entering and exiting systems, and store the results in an organized manner. We are also grateful to the many veterans of mine drainage treatment who helped us understand basic questions like how it works, who does it, and who funds it.

Through the work we learned that areas whose streams are most affected by untreated discharges have much lower property values and household incomes. This is not surprising; having seen these discharges, I wouldn’t want to live near a stream that can’t be enjoyed and that might expose my children to harm. On the encouraging side, we also found that the systems are on average improving the water quality of discharges and preventing them from impairing long stretches of water downstream. Although many more miles of stream remain impaired by mine drainage, there is reason for optimism. The success of past systems, the lessons learned, and now a historic federal funding boost will enable states like Pennsylvania to address many of their remaining discharges.

Follow the Topic

-

Communications Earth & Environment

An open access journal from Nature Portfolio that publishes high-quality research, reviews and commentary in the Earth, environmental and planetary sciences.

Related Collections

With Collections, you can get published faster and increase your visibility.

Archaeology & Environment

Publishing Model: Hybrid

Deadline: Mar 31, 2026

Drought

Publishing Model: Hybrid

Deadline: Mar 31, 2026

Please sign in or register for FREE

If you are a registered user on Research Communities by Springer Nature, please sign in