When Sound Feels Like a Gentle Touch

Published in Neuroscience and Behavioural Sciences & Psychology

Why we looked to touch

Motivated by this paradox, our paper asks a straightforward question: why do some individuals report stronger ASMR “tingles” than others? We examined two candidate dispositions: (i) sensitivity to affective (pleasant) touch, and (ii) interoceptive accuracy—the ability to perceive internal bodily signals (e.g., heartbeat). If ASMR simulates intimacy at a distance, we hypothesized that individuals who find gentle touch especially pleasant would exhibit stronger ASMR responses, despite the absence of physical contact.

Affective touch is mediated by a class of unmyelinated C-tactile (CT) afferents concentrated in hairy skin (e.g., the forearm) and tuned to slow, gentle stroking. Activation of this system is closely associated with comfort, bonding, and relaxation. Because many people describe ASMR as “sound that feels like a soft caress,” affective touch offered a principled starting point. In parallel, ASMR studies frequently report subjective calm and parasympathetic shifts, suggesting a plausible contribution of interoceptive processes. We therefore asked which of these dispositions—heightened sensitivity to affective touch or greater interoceptive accuracy—better accounts for the intensity of tingles reported during ASMR viewing.

What we did

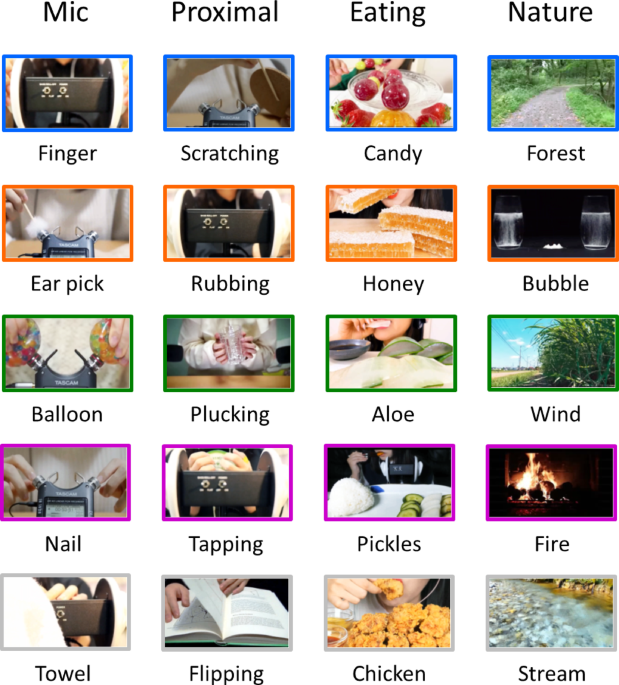

We combined three tasks within a single 60-min session. First, participants viewed short ASMR clips and reported tingling intensity continuously (0–3) by pressing and holding keys, giving us second-by-second traces rather than retrospective summaries. The clips spanned four categories: microphone interactions (direct contact with a binaural microphone), proximal hand–object sounds (near-microphone actions without contact), eating (e.g., candy, honeycomb), and nature (non-social environmental controls).

Second, to assess affective touch sensitivity, a trained experimenter gently brushed the forearm (hairy, CT-rich) and palm (glabrous, CT-sparse) at five velocities (0.3, 1, 3, 9, and 27 cm/s). After each 6-s stroke, participants rated pleasantness (0–10). We then computed a sensitivity score as the pleasantness at CT-optimal speeds (3–9 cm/s) minus the pleasantness at very slow speeds (0.3–1 cm/s).

Third, for interoception, participants performed a heartbeat-counting task across several intervals while a wearable sensor recorded actual heartbeats, allowing us to derive an accuracy index (the correspondence between reported and recorded counts).

Behind the scenes, the most delicate element was maintaining a constant brushing speed. We used a pacing cue—a moving marker on a monitor—to standardize strokes, and a goat-hair brush to ensure soft, consistent contact. We also scheduled the heartbeat task between the ASMR and touch tasks to minimize mood carryover, since ASMR can induce marked relaxation—as intended.

What we found

In brief, individuals with greater affective-touch sensitivity reported stronger ASMR tingles—most prominently for eating sounds—whereas interoceptive accuracy showed no meaningful association. Forearm-based sensitivity (the CT-rich site) correlated positively with tingling intensity in the eating condition and remained a significant predictor in a category-specific regression model. For the microphone, proximal, and nature clips, associations trended positive but did not survive correction for multiple comparisons.

We also replicated the classic affective-touch function: CT-optimal stroking elicited the highest pleasantness on average. Together, these results support the view of ASMR as “heard touch,” with affective-touch sensitivity acting as a gain factor—amplifying the tingling response in those who are especially responsive to gentle touch.

Why eating sounds?

We think socially grounded expectations are central. Eating is intrinsically multisensory and embodied; at close range, bite and mouth sounds arrive with inferred tactile qualities—texture, viscosity, and warmth. Even with faces and voices removed to minimize social confounds, the clips still conveyed proximity and care, akin to being offered food within one’s peripersonal space. In that context, individuals with heightened affective-touch sensitivity tended to report stronger tingles. This pattern is consistent with views of ASMR as digitally mediated intimacy, in which familiar social dynamics are distilled into sensory cues that the nervous system interprets as touch-like and comforting.

What it means

If ASMR recruits the same affective-touch circuitry that renders a slow caress soothing, then variation in tactile affect should modulate ASMR responsiveness. Our findings support this prediction: individuals with greater affective-touch sensitivity reported stronger tingles, most notably for eating sounds. Conceptually, this sensitivity may function as a gain factor on “heard touch.” Practically, the result argues for personalized ASMR—tactilely evocative triggers for touch-sensitive viewers, and different triggers for others. By contrast, the null association with heartbeat counting underscores that interoception is multidimensional; facets beyond simple accuracy (e.g., awareness or implicit interoceptive signaling) may still matter, even if they were not captured by our measure. Taken together, these points refine theoretical accounts of ASMR and inform the design of evidence-based content for relaxation and well-being.

What’s next

Our thanks to the participants and to the creator who permitted use of their clips. If you’re curious about “heard touch,” put on headphones and cue a trigger; notice how the sensation unfolds—scalp to spine for some, a quiet settling in the chest for others. The takeaway is simple and durable: under the right conditions, sound behaves like touch—a bridge we can now study, and design for, with greater precision.

Follow the Topic

-

Scientific Reports

An open access journal publishing original research from across all areas of the natural sciences, psychology, medicine and engineering.

Related Collections

With Collections, you can get published faster and increase your visibility.

Reproductive Health

Publishing Model: Hybrid

Deadline: Mar 30, 2026

Women’s Health

Publishing Model: Open Access

Deadline: Feb 28, 2026

Please sign in or register for FREE

If you are a registered user on Research Communities by Springer Nature, please sign in